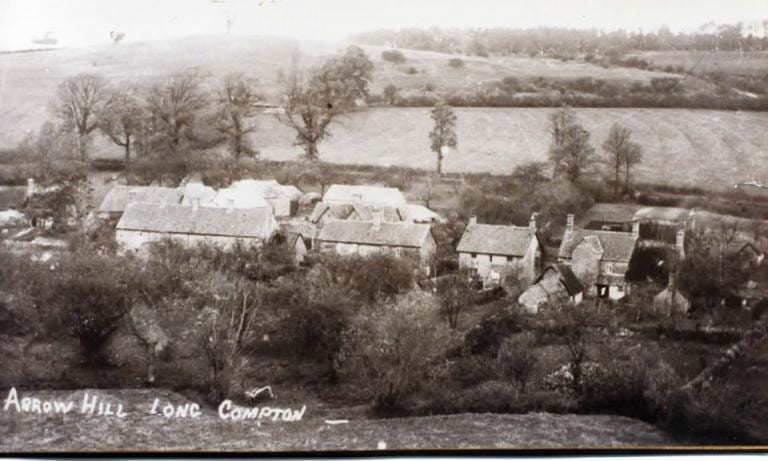

From the birthplace of the world’s most famous modern magician, Aleister Crowley, Golden Dawn founder William Wynn Westcott, as well as playing home to the coven of Bob Clay-Egerton in the early-late Twentieth-Century, Warwickshire has been a host to stories of magic and witchcraft for many years. With the mysterious death of Charles Walton on Valentine’s Day 1945 at the ancient and wind-swept Iron Age camp of Meon Hill, Scotland Yard’s premier detective descended, as did the media. In the drama that circulated around the murder, modern witchcraft expertise was sought to eliminate the occult ritual connection and none other than Margaret Murray (1863 – 1963), pioneer of the now debunked theory of ancient fertility religions, waded in with her opinion of the tragic slaughter of a poor, elderly farm worker. Indeed, even Gerald Gardner (1884 – 1964) was drawn to remark upon the case in his book The Meaning of Witchcraft (1959), and the late Mike Howard (1948 – 2015), former editor of The Cauldron and authority on Traditional Witchcraft, was drawn to the incident. What drew so much attention was the supposed similarity to an earlier murder in the nearby village of Long Compton, whereby a pitchfork was used and quickly became identified as a ritual object for the slaying of witches. Unfortunately, the theory utterly sidesteps the likelihood of farm labourers to be in possession of such implements in the course of their everyday work, making the relevance of the murder weapon less mysterious and more mundane. This earlier murder created a good deal of hype at the time and even garnered remark in The Times in the heart of London, ridiculing parochial superstition and magical inclinations. Achieving a level of celebrity, the murderer would later embellish his story as time pushed him ever farther from the crime and his popularity increased, with occasional sensation seekers visiting him in his incarceration. It was his famous lines that would cement Long Compton in the history of witchcraft in the 20th Century when he remarked to some that there were sufficient witches to be found in Long Compton that they could push a cart up nearby Meon Hill. Indeed, by the time of Robert Cochrane’s letters in the 1960s, the position of Long Compton as the premier location for the oldest and largest of the witch covens in Britain was established enough to be remarked upon in passing.

Being a native of Warwickshire, and with a deep interest in local history, I studied the case of Anne Tennant with great interest. The following article was published in White Dragon No. 59, Imbolc 2009, and is the summation of my findings. Unfortunately for those who would further the more sensational history, the truth is rather more mundane and it is with confidence that I declare that the person of Anne Tennant, and most likely Charles Walton, was in no way involved in witchcraft. In the former case, mental illness and superstition are the factors involved in the tragic death of an elderly woman, while the latter was most probably motivated by theft or local grudge. To learn more about the details of this conclusion, I present here the faithful reproduction of the article as it appeared in 2009:

“There are fifteen more of them in the village that I will serve the same. I will kill them all.”

Warwickshire witchcraft can rarely be mentioned these days without reference to the village of Long Compton. Many are the rumours of witches said to have one inhabited this quiet and rural area towards the Cotswolds. Among the most frequent names mentioned is that of farm labourer, Charles Walton, famously murdered on Valentine’s Day 1945. However, here we will look at another murder victim that was recalled by inspectors investigating the Walton case as evidence of bewitching as a motive for gruesome homicide in the local villages around Meon Hill. Using the inquest report and an article from the Stratford Advertiser reporting upon the murder, the facts of the case of poor Ann Tennant show how much water the bewitching charge, discredited as the ravings of a madman, actually holds. Here we may discover the origin and source of many of the stories associating this part of Warwickshire with witchcraft.

On Wednesday 15th September 1875, a farm labourer returning home from a day’s work viciously attacked an elderly lady. The attack left Ann Tennant bloody and dying, while the assailant was arrested for her murder. James Hayward showed no remorse for attacking Ann Tennant, insisting that she was the leader of a coven of fifteen other witches in the area, all of whom he could name and would deal the same treatment if he would be allowed. Moreover, he expressed his lack of concern that she could die from her wounds.

James Hayward was not alone in his belief in bewitchment at the time, although he did display an unusual conviction in his behaviour towards what could be regarded as folk superstition. His fervent beliefs were frequently remarked upon in statements at the Coroner’s Inquest and such was Hayward’s conviction that bewitchment was to blame for his misfortune that he had previously sought out that folk figure who is renowned for opposing witchcraft: the Cunning Man.

The local Cunning Man and Water Doctor, known enigmatically as Manning*, apparently gave Hayward a method for identifying bewitchment by inspecting his urine. Once the cause was apparent, it has been speculated that the Cunning Man informed Hayward of the best way to rid himself of the problem. More accurately, the method of getting the better of the witch, and removing their power, is to draw blood on them. The story goes that Manning told Hayward to “turn upside down a bottle or phial filled with his urine. If bubbles came to the top it would mean that he was, indeed, under a spell”[1].

Some stories claim that Hayward provides a source for the later murder of Charles Walton in that the prescribed method of killing a witch was to pin them to the ground with a pitchfork and slash the throat, or else carve a cross in the chest. Indeed, Hayward is quoted as having said this in some later sources. The apparent culprit linking the Tennant case with the murder of Charles Walton is a 1906 book, Warwickshire by Clive Holland. Here we find reference to Hayward’s ‘traditional’ method of killing a witch, which demonstrates no historical precedence that could lead us to believe it anything other than a fabrication. This book was, according to the story, shown to Fabian of the Yard (Scotland Yard’s detective in the Walton case) whilst investigating the murder of Charles Walton and the link to witchcraft and ritualised murder was sealed in time and legend. Unfortunately, the perpetuation of liberties with the facts concerning Ann Tennant fails to acknowledge that she was not, in fact, murdered in the prescribed method but died after receiving multiple puncture wounds to her legs from a frenzied attack, seemingly intended to draw blood but not kill, per se.

… Hayward wanted to show me some witches that were in the jug of water… He said it was only those that had witches about them that could see them.

The problem with anything ascribed to Hayward is that the facts have been adapted to fit a story of Warwickshire Witchcraft. Most believe Hayward died refusing food and drink in Warwick gaol when, in reality, he was declared a ‘madman’ and spent the remainder of his years in Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum where he apparently died at the age of 59. One report tells us that there are enough witches in Long Compton to pull a cart up Meon Hill. Sadly, this quote is derived from a man convinced of his own bewitchment and ill-fortune that he was prepared to commit murder in a fit of rage and face being labelled insane in order to break a spell. Even while being held pending the inquiry, Hayward was trying to prove his bewitchment using the water and urine method shown him by Manning. The question remains, though, what drove Hayward to such a rigid and harmful belief.

The folklore of Warwickshire makes a number of enigmatic references to Long Compton witchery, including the story of a young man marking a circle and reciting the Lord’s Prayer backwards (see Mastering Witchcraft by Paul Huson for a contemporary rendition) to summon the Devil [2]. Just a decade before the murder of Ann Tennant, there was another victim attacked for bewitchment in nearby Stratford upon Avon, toward the south of the county. John Davies believed that the only sure way to rid himself of bewitchment was to draw the blood of the witch and was charged with assaulting Jane Ward after causing a gash in her cheek [3]. So, the killer of Anne Tennant was not an isolated account of such a belief in the area. Charles Godfrey Leland (1824 – 1903) in his Etruscan Roman Remains cites a similar belief among Venetians, that a witch loses their power if wounded and their blood spilt.

On the fateful day, 1875, James Hayward had been working with others in a harvest field and was returning home at around eight o’clock in the evening. Sadly, Ann Tennant was also on the turnpike road after fetching a loaf of bread and, upon seeing the elderly lady, Hayward struck Tennant several times with a two-pronged fork and inflicting fatal wounds upon the 79 year-old. When the police constable arrived and arrested Hayward at the scene, the inquest reports that the assailant remarked: “There are fifteen more of them in the village that I will serve the same. I will kill them all.” [4]

Hayward blamed his poor work in the harvest field that day on Ann Tennant, who he claimed had possessed him and, at the sight of her, he stabbed her in the legs with his fork before witnesses restrained him. The comparison with the murder of Charles Walton, and the idea of a ritual method for disposing of a witch, is here diminished by the testimonies of the many witnesses at the Coroner’s Inquest, held at the Red Lion Inn the following Friday.

There is no mention of a bill-hook (a hedge laying tool) or the slashing of Tennant as Hayward was concerned with nothing other than drawing blood upon the old woman. It appears that Hayward lost control of his wits and was thrown into a violent rage after the first blow landed. One is inclined to believe that it was not the original intent, however fleeting that may have been, to murder poor Tennant. There is irrefutable evidence to the affect that he had declared no regret should the old lady die during his arrest, even suggesting that there were more women he might kill if opportunity afforded him the chance. However, these seem to be the ravings of a man in the grip of a fury, his wits having left him entirely. It is clear from later remarks to the Police Superintendent that he hadn’t meant to “kill her outright”[5], but rather he was acting spontaneously.

Hayward’s obsession with witchcraft is revealed in the inquest through several of his comments regarding witches. James Thopson, Police Superintendent, remarked that Hayward “…wanted to show me some witches that were in the jug of water… He said it was only those that had witches about them that could see them“[6]. The jury at the Coroner’s Inquest recored a verdict of “wilful murder” and the killer was to stand trial at Warwick Assizes. The witness statements confirmed that Hayward was excited and frenzied during the attack, while the victim’s husband and daughter both confirmed a long acquaintance of some 30 years with the murderer, reflecting upon his persistent delusions about witchcraft.

There seems little resemblance between this tragic homicide and the murder of Charles Walton on Meon Hill some 70 years later. Furthermore, some of the more often repeated rumours concerning the sixteen witches of Long Compton originated in statements made by Hayward, who was subsequently committed to a criminal asylum. Since the murder of Charles Walton in 1945, it has been accepted to associate Meon Hill, the close by ancient megalith of the Rollright Stones and the village of Long Compton together in a local diabolic pact where witches consort and bring about bewitchments, ritual murder being the only means of escape for the unwitting victims. The increased interest in witchcraft in the latter half of the last century brought a great many occultists to the area and legend was taken as evidence of a long-standing tradition of witchcraft connecting ancient practices with modern pagans. The occurrence of a couple of attacks against individuals accused of bewitching in the 19th Century is less a testament of surviving practices as it is of lingering folk belief. That one of those assaults resulted in the death of poor Ann Tennant enabled the story to reach a wider audience in early sensational press and has appealed to lazy research into historic witchcraft.

Without question, there is little similarity between the case of Ann Tennant and that of Charles Walton. The coincidental item of fact that occurs in both incidences is the use of the two-pronged pitchfork as a weapon. This is itself does not prove witchcraft or ritual murder in either case as the pitchfork remains a common implement of labour in rural communities. Given that both James Hayward and Charles Walton were farm labourers in the act of working, the pitchfork would be conspicuous only by its absence.

The case of Ann Tennant provides insufficient evidence to enable a satisfactory argument for her being involved in witchcraft, least of all the leader of a coven of fifteen based upon items found to be floating in her murderer’s urine. Given the details available at the inquest, it is apparent that the accusations do not merit serious consideration and receive no corroboration from the community, neighbours and families, as one might expect. In light of the post attack material, Ann Tennant appears to be nothing more than a classic case of wrong place, wrong time. In addition, this author has found no reference to Ann Tennant being associated with bewitching prior to her tragic death. Several websites and rumours abound with statements concerning her use of toads in nefarious magic, and diverse craft practices. None of these claims can be verified and it is safe to say that, like many who suffered at the hands of hysterical individuals, Ann Tennant, the witch of Long Compton, had no such association.

In conclusion, we must deduce that Ann Tennant was the victim of an unbalanced mind struggling with misfortune and hardship and prone to superstition – aside from the framing and the content, some things haven’t changed and ‘fake news’, misinformation and conspiracy theories abound today to replace the fears and scapegoats of yesteryear. Speculation over the years, together with the speculation of twentieth Century occultists, anthropologists and folklorists has fuelled and exaggerated details, creating a modern legend. James Hayward was known to speak frequently of witches preventing him from his labours, a notion identified by his neighbours and colleagues as a delusion. Belief in witches in and around Long Compton was prevalent in the last century and we may not say with certainty that there ever were witches operating out of the area. Much more certain is that modern witches are most assuredly evident today.

With thanks to Ron and Diane Jeavons for sharing the Coroner’s Inquest and Advertiser articles.

* Manning belonged to a family of cunning men, his father and brother both being practitioners — see the entry on Manning in Michael Slater’s wonderful The Old Woman and the Conjurers, Llewellyn, 2020

- Folklore of Warwickshire, Roy Palmer, Tempus Revised Ed. 2004

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Inquest testimony of John Simpson, Police Constable, given at the Red Lion Inn, Long Compton, 17th September 1875.

- Inquest testimony of James Thopson, Police Superintendent given at Red Lion Inn, Long Compton, 17th September 1875.

- ibid.