I would like to invite you to open your mind and heart to two different stories. The first is a cautionary tale from the past. The second is a hopeful story of a possible future. I chose these two particular stories because we are in close proximity to two important dates:

- Today is the 50th Anniversary of the Kent State massacre.

- This past Friday was May 1st, known as “International Workers’ Day” or May Day, an annual celebration of the working classes that dates back more than 130 years to the late nineteenth century.

It is, by the way, quite telling that here in the U.S., we currently celebrate Labor Day in September—a date idiosyncratic to our own country—instead of on May 1st, in solidarity with the international labour movement. It matters which stories we choose to tell—and when.

Let’s start with a difficult story from the past before shifting to a more hopeful story of our future. This first story happened fifty years ago tomorrow, on May 4, 1970, on the campus of Kent State University in Ohio. Over the course of thirteen terrible seconds, twenty-eight members of the Ohio National Guard fired sixty-one bullets at a group of unarmed college students protesting President Nixon’s decision to expand the Vietnam War by invading Cambodia. Four students were killed and nine wounded, one of whom was permanently paralyzed (Grace 245).

Let’s start with a difficult story from the past before shifting to a more hopeful story of our future. This first story happened fifty years ago tomorrow, on May 4, 1970, on the campus of Kent State University in Ohio. Over the course of thirteen terrible seconds, twenty-eight members of the Ohio National Guard fired sixty-one bullets at a group of unarmed college students protesting President Nixon’s decision to expand the Vietnam War by invading Cambodia. Four students were killed and nine wounded, one of whom was permanently paralyzed (Grace 245).

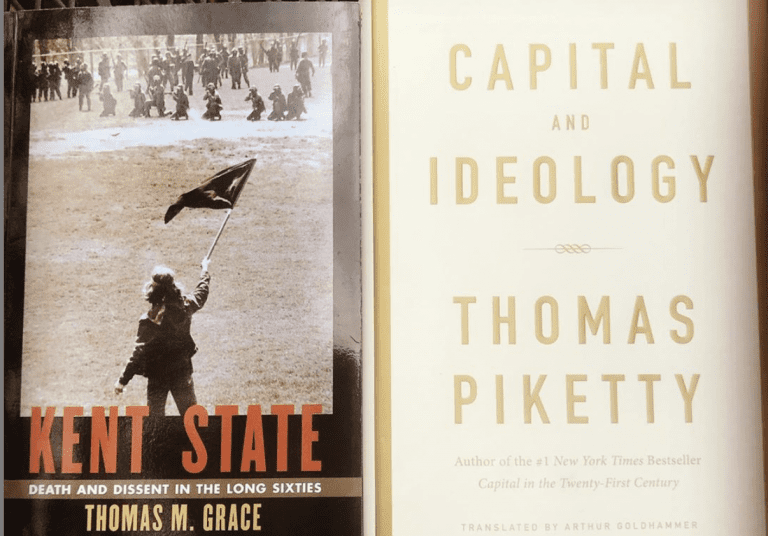

There is a lot to say about all that happened before, during, and after the Kent State Shooting. If you are interested in learning more, I recommend the book Kent State: Death and Dissent in the Long Sixties by historian Thomas Grace (University of Massachusetts Press, 2016). For now, I will let words of the Scranton Commission, which was tasked with investigating the shootings, serve as a summary:

Though it found the behavior of some protesting students at Kent to have been “dangerous, reckless, and irresponsible”…firing on them was “unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable…. Even if the guardsmen faced danger, it was not a danger that called for lethal force…. [It concluded that] the Kent State tragedy must mark the last time that, as a matter of course, loaded rifles are issued to guardsmen confronting student demonstrators.” (245)

For me, this tragedy is a sacred story, if it is not too strange to say so. It is a sacred story of sacrilege, a sacred story of desecration that reminds us of what it looks like when there is a violation of “the inherent worth and dignity of every person,” which my chosen tradition of Unitarian Universalism holds as its First Principle, drawing from the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights. The Kent State massacre is a story that reverberates with the sacred in each of us, calling us to do everything in our power to prevent such a desolating sacrilege from happening again.

I will share with you a few brief examples of how this sacred story of sacrilege has powerfully shaped lives connected to the Unitarian Universalist movement, and there are many many examples from other individuals and movements.

First, Howard Ruffner. On May 4, 1970, Ruffner was a sophomore broadcast journalism major at Kent State. He took the famous photograph that appeared on the cover of LIFE Magazine —the one that inspired Neil Young to write the song “Ohio”—as well as four photos that appeared on the inside of that issue. (In that cover photo, the name of the injured student is John Clearly. Thanks to the first aid of those students surrounding him, he did survive. Today he is sixty-eight years old, living outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.)

I don’t know when photographer Howard Ruffner became a UU, but he has been part of a number of UU congregations over the years, and is married to Lark Matis-Ruffner, who served as Minister of Religious Education at Jefferson Unitarian Church in Golden, Colorado. If you are interested in learning more, last year Ruffner released a book with his photos from fifty years ago, titled Moments of Truth: A Photographer’s Experience of Kent State 1970.

A second person whose life was shaped deeply by that day was my colleague The Rev. Barbara Child, who retired as a UU minister in 2010. Fifty years ago, she was an English professor at Kent State. She ran from the gunfire and was marched off with a bayonet at her back. Looking back, she has reflected that, “The massacre that day and its aftermath have more to do with who I am today than anything else in my entire life….” Indeed, she has said, “I am a minister today because I was there that day.” (Rev. Child’s reflections on the 50th anniversary are available here.)

Third, the Rev. Bill Schulz: on May 4, 1970, Bill was a pre-theology major at Oberlin College, working part-time as the student minister of the UU Church of Kent (Post-Gazette). His involvement with the aftermath of the shootings catalyzed what would become a lifelong commitment to human rights, as you can see in the titles of many of his books:

- What Torture Taught Me: And Other Reflections on Justice and Theology (2013)

- Tainted Legacy: 9/11 and the Ruin of Human Rights (2003)

- In Our Own Best Interest: How Defending Human Rights Benefits Us All (2001)

After serving as President of the Unitarian Universalist Association (1985-1993), his commitment to human rights led him to become Executive Director of Amnesty International (1994-2006)—and in a final job before retirement, President of the UU Service Committee (2009-2016).

We are also approaching the fiftieth anniversary of a less well-known tragedy. A mere eleven days after Kent, in Mississippi, at Jackson State college (now Jackson State University), “Police fired for twenty-eight seconds—150 rounds in all…. Many of the shots were fired into the women’s dormitory, where six coeds were hit. Five African-American men were also wounded. Worst of all, two young people were killed…” (238).

It is hard to hear such stories. But we need to tell them from time to time, especially on signifiant anniversaries, both to honor the memory of all those killed or impacted and because we need such stories to shape us—to embolden us to act in any way that we can to prevent such desecrations from being repeated. Indeed, scholars of nonviolent activist movements tell us that, historically, the turning point in overthrowing a dictator or authoritarian government has often been the precise moment when the police or the military are given the order to shoot unarmed protesters—and their conscience stops them from following the order (Engler and Engler 247). It matters which stories we hold sacred. It matters which stories we choose to tell.

Along those lines, I want to begin to shift from this story of sacred story of sacrilege in the past to a story of sacred imagination about the future world we might be a part of building. As the saying goes, for many people “It is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism” (Capitalist Realism). We can see this truth playing out every day, with leaders desperate to return to so-called “normal life” due to an inability or unwillingness to imagine a better way.

One guide I have found helpful in recent years, for helping me better imagine how we might build the world we dream about, is the French economist Thomas Piketty (1971 – ). Piketty first came to my attention through his 2013 bestseller, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013).

The Unitarian Universalist tradition of which I am a part has some pretty big goals, such as the UU Sixth Principle, “The goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all.” One of my biggest takeaways from Piketty’s book is that if we want to get serious about such big goals, we would need serious structural change to get there. One major tool Piketty suggests is the need for a “global wealth tax.”

Now, seven years after his first major book, Piketty has recently published another huge doorstop of a book titled Capital and Ideology. Why does he keep working so hard? He is convinced that the way things are is not the way they have to be, and he wants to make sure we have the data for both the problem and some potential solutions. He wants to help us as a species to live in to a more hopeful future story.

He wants us, for instance, to get better at telling the story of why our current global wealth gap is inhumane and unsustainable. I don’t want to overwhelm you with numbers, but allow me to point you to a few charts drawn from Piketty’s book. Notice in this slide how little the bottom 50% have, and how comparatively much the top 10% control.

Here’s a related slide about annual income (instead of accumulated wealth) that shows one reason why the wealth gap is increasing. Notice the green line for the U.S. Even more importantly, notice that the lines on this chart do not stay at the same level over time. Change happens, which invites us to consider what we might change to get a more equitable distribution of wealth.

This slide illustrates further that, in recent decades, the change has been increased wealth at the top “at the expense of the bottom 50 percent.” And if we zoom out, this slide shows that a similar dynamic of rising inequality has been playing out across the world.

Ok, if you’re still with me, only one more nerdy chart! There actually was “a relatively egalitarian phase between 1950 and 1980” (22). But wealth inequality has been increasing for the last three decades (25). What changed? Simply put, this slide shows how we lowered taxes on the wealthiest among us, allowing an increasingly large amount of money to pool at the top (32). Note that we have moved toward everyone paying closer to the same tax rate—even as some among us have vastly more and others not even a bare minimum.

I should add that I’m not saying that we should try to reach a world of complete equality. I continue to think that “profit motive” matters. But we must learn to balance the so-called sole “bottom line” of profit alone—as if money were the only thing that mattered—with what has been called the Triple Bottom Line of people, planet, and profit. Along these lines, Piketty defines a “just society as one that allows all of its members access to the widest possible range of fundamental goods…” (967). Sometimes this goal is imagined as a “stable floor” for all, such that everyone is guaranteed the minimum needed to live a safe, fair, and dignified life.

Now if you really want to dig into the details, Piketty’s book weighs in at more than 1,000 pages. But for our purposes of imagining how we might build a better world, I’m going to share with you just a few highlights from Piketty’s writings.

I’ll start with an intentionally provocative question: Should billionaires exist in a just society (Piketty 987)? We currently have a dominant story in our society that a billionaire represents a success story. But what if we flipped the script and considered whether a billionaire represents our failure as a society to curb exorbitant wealth?

I’ve shared before about the need for a stable floor for all, beneath which we don’t allow anyone to sink. Likewise, I invite you to consider whether a just society should also have a ceiling past which there is a 100% tax rate—so that a few individuals cannot become so disproportionately wealthy that they can unduly interfere with the democratic process.

I don’t know precisely where such a ceiling should be set, but it is worth considering it is should be somewhere south of a billion. To say more about what I mean, it is worth take a few moments to reflect on just how large a number a billion is:

- Imagine that a magical genie granted you a wish to receive a dollar each second, it would take you a mere 11.4 days to become a millionaire. But even at the rate of a dollar per second, it would take almost 32 years for you to become a billionaire (Branko 41-42). (That’s how much bigger a billion is than a million.)

- Or suppose a rich relative died and left you either $1 million or $1 billion, and you decide to celebrate by spending $1,000 every day. It would take you less than three years to spend one million dollars at the rate of a thousand dollars per day. In contrast, in the case of $1 billion, it would take you “more than 2,700 years to blow your inheritance” (ibid). That’s how much bigger a billion is than a million.

If we had more time, I could give you related examples on an even greater order of magnitude about why it really matters that some mega-corporations have passed the trillion-dollar level, including Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Alphabet (Google’s parent company). But the billion-dollar level matters as well. There are slightly fewer than 1,500 billionaires in the world. That “super-tiny group of individuals and their families control about 2 percent of world wealth.” (ibid).

Piketty suggests that a solution to this problem might be a progressive wealth tax. Instead of the hugely unpopular 20-30% tax all at once at the end of your life when one’s estate is passed on to one’s heirs, a much easier and more popular approach might be a 1-2% tax on wealth over a period of decades for those individuals and corporations which have amassed a certain level of wealth (978).

Beyond funding the social goals of universal health care, universal access to quality education through college or vocational training (1007, 1011), and a Minimum Basic Income (1002), Piketty has crunched the numbers such that a properly instituted set of taxes could further fund a Universal Capital Endowment “given to each young adult (at age 25, say…which would open up new possibilities, such as purchasing a house or starting a business”)” (981, 983) just as wealthy parents often do now.

As I move toward my conclusion, I should underscore that what is most important is not whether any of us agree with any one or more of Piketty’s specific suggestions. Rather, my hope has been to open our sacred imagination: to dream more vividly about what a world might look like with peace, liberty and justice—not merely for some—but for all.

The stories we choose to tell matter:

- from sacred stories of sacrilege in the past (such as the Kent State shootings) that we hold in our hearts as a reminder to do all in our power to help prevent such desecrations from happening again,

- to stories of sacred imagination about a better future for all.

The headlines that we are watching play out each day in the news, around the many workers who are apparently both “essential” and underpaid and under-resourced, is a reminder that the way things are is neither just, nor fair, nor sustainable for most humans nor for this planet. We can and must demand better for ourselves, for the Earth, and for generations to come.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles