If you hang out long enough with social justice activists, you’ll eventually hear the classic slogan “Another world is possible.” You can find it spray-painted as graffiti on subway walls, and emblazoned on t-shirts. You can spot it on lapel buttons. The phrase “Another world is possible” invites us to imagine what might be—to remember that the way things are is neither the way they’ve always been nor the way they have to be.

In the words of the late social justice activist Grace Lee Boggs (1915 – 2015), “Another world is necessary. Another world is possible. Another world is happening.” But what kind of world will that be? A world with peace, liberty, and justice increasingly for all—or one with peace, liberty, and justice reserved for only a select some, or hoarded by an elite few?

Last Wednesday, many citizens of this country had an experience of what it feels like when another world begins shifting into place. As we approached midday Eastern time, a new President of the United States was sworn in—as well as the first female, first African American, and first Asian American Vice President. At that moment, many people (especially of the progressive activist persuasion) breathed a long sigh of relief, release, or even joy—and had an embodied experience that another world is possible.

That Wednesday morning, the words of the Indian author and activist Arundhati Roy (1961-) felt palpably true for many people around the world: “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.” Can you feel that right now, in real time, in this moment?

Another world is possible. And it is also true that there are no guarantees that such potentialities will come into their full fruition. Indeed, a slight tweak on the slogan we’ve been exploring—one sometimes found scribbled on subway walls—is that “Another end of the world is possible.”

The last four years have given us a traumatic, embodied experience of that undesirable possibility as well. The past few weeks alone have been a wild rollercoaster of emotions. Over the course of three Wednesdays, we have collectively experienced:

- Wednesday, January 6: The storming of the United States Capitol

- Wednesday, January 13: The second impeachment of Donald Trump

- Wednesday, January 20: The inauguration of Joe Biden as the 46th President of the United States.

That’s a lot of sturm und drang to process in a mere two-week period. Yet, another world is possible, and it is up to us—up to “we, the people”—to keep our hands on the wheel so that the world that becomes possible is the world we dream about, not the world of our nightmares.

In my own chosen tradition of Unitarian Universalism, the Universalist side of UU history offers a powerful reminder of forebears who have been part of movements to show that another world is possible:

- 1700s: universal salvation from hell in a “next world” (which transformed into “loving the hell out of this world”)

- 1800s: universal freedom from enslavement (abolition)

- 1900s: universal suffrage (for women) and civil rights (for African Americans)

- 2000s: universal marriage rights (for people who are LBGTQ+)

Each of those dreams were called unrealistic before social justice activists pushed us to prove that another world is possible. Remembering this past can embolden our work of continuing to turn our dreams into deeds. This trajectory could mean advocating for similar universalist goals such as

- universal health care,

- universal education through college or vocational training, and a

- universal basic income (we’ve gotten a glimpse of what this looks like with COVID stimulus checks)

Keep that history in mind as we prepare to imagine how another world is possible in regard to mass incarceration. It is OK for many of us to admit that, it can be difficult, frightening, or even overwhelming to try to imagine a world without prisons; but I invite you to consider that it is urgent that we try. So many human lives are at stake.

As Joshua Dubler and Vincent Lloyd have explored in their important book, Break Every Yoke: Religion, Justice, and the Abolition of Prisons (Oxford University Press, 2019), our prison-abolitionist imaginations can be inspired if we keep in mind our abolitionist forebears who went before us in making the seemingly impossible possible—who “made a way out of no way”—in their time and place, such as John Brown and Nat Turner, Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony and Sojourner Truth, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcom X, union members on strike and Stonewall rioters—and more recently, #OccupyWall Street activists and #BlackLivesMatter organizers (10).

In regard to the plague of mass incarceration, the two people who have done the most to awaken, challenge, and inspire our collective imagination are Michelle Alexander, through her book The New Jim Crow (2010) and Ava DuVernay, through her Netflix documentary 13th (2016). If you are looking for a starting point, that book and/or film are great places to begin. Both make a powerful, compelling case for taking the first step, which is admitting we have a problem.

I’ll lay out just a few of the most troubling facts. Beginning in the 1970s, we started imprisoning our fellow citizens of this country at an increasingly horrifying rate (Dubler and Lloyd 2):

- “The number of people incarcerated in the United States has quintupled [multiplied five times] since the 1980s, to a total of almost 2.2 million. Forty years ago, our rates of imprisonment were comparable to those of our peer nations, but now, “our level of imprisonment is five times higher than that of other liberal democracies—nine times higher than Germany’s [rate of incarceration] and seven times France’s.”

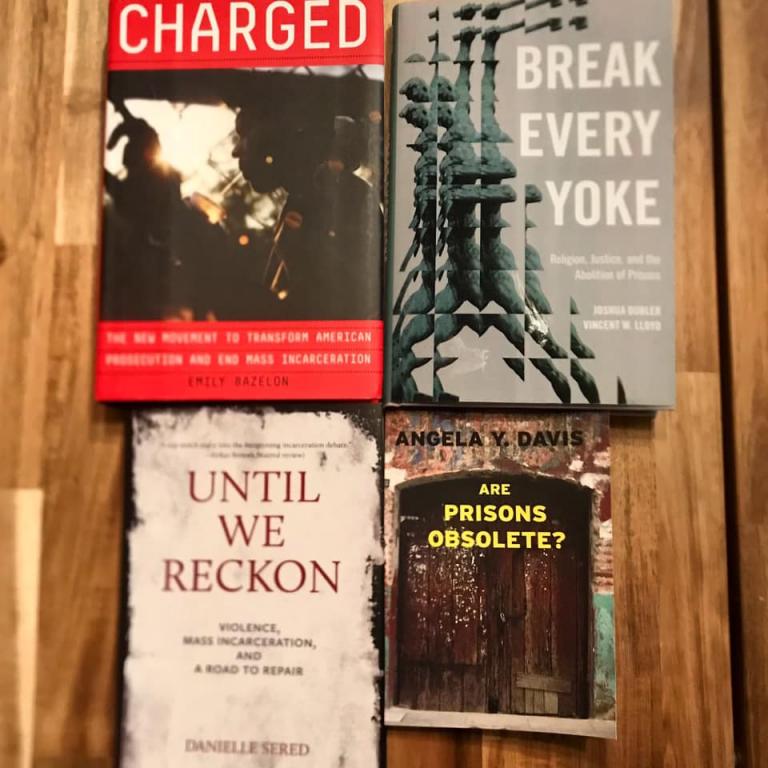

- And due to systemic racism, Black defendants have been routinely “punished more severely than white defendants for similar crimes,” creating gravely unfair and harmful disparities upon those most impacted by mass incarceration (Bazelon xxv).

- The result is that the number of Black people incarcerated or placed under correctional control exceeds the total number of adults enslaved in 1861” (Sered 7-8). We have a problem. And it is statistics such as these that can help us understand why contemporary prison abolitionists have adopted the same abolitionist label as their nineteenth century forebears who worked to abolish enslavement.

- Even beyond racial categories, it is important to realize that, “No country has locked up their own people at the rate we do. The United States has 5 percent of the world’s population and nearly 25 percent of its incarcerated people.”

- Moreover, mass incarceration is an expensive problem that is undermining other priorities: “Over the past three decades, state and local government expenditures on jails and prisons have increased roughly three times as fast as spending on elementary and secondary education” (Sered 9).

- “We spend $43 billion a year on prisons and jails, at a cost of $15,000 to $70,000 annually per prisoner.”

Amidst these dire statistics, one source of hope is that, “Falling crime and mounting costs are opening a window for deep reform” (Bazelon xxviii).

Since mass incarceration has been a major problem for a long time, it may also help to tell you a little of the story about how I began to feel it was increasingly important to research, write, and advocate more on topic. A little more than five years ago, in June 2015, I was attending a business session at the annual Unitarian Universalist Association General Assembly that was debating the language in a proposed Action of Immediate Witness in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Years can begin to blur together, so it may be helpful to recall just a few of the events that led up to that summer of 2015’s debate, because it helps us understand the rising sense of urgency at that time. The #BlackLivesMatter movement had just begun, two years earlier in summer of 2013, in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman for killing Trayvon Martin.

The social media organization, #BlackLivesMatter, helped focus the world’s attention until the next summer in 2014, when Eric Garner was strangled to death by a New York City police officer, and a few weeks later, Michael Brown was killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. Then, in the months immediately before the June 2015 debate at the UU General Assembly over support for the #BlackLivesMatter movement, Walter Scott was killed in Charleston, South Carolina, and a little more than a week later, Freddie Gray was killed while in police custody in nearby Baltimore, Maryland.

At the UU General Assembly in that summer of 2015, there was an overall sentiment that we needed to pass a statement supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. But from what I recall, the most contentious debate was over whether the action statement should include the two words that encouraged UUs to work toward “prison abolition.”

I remember folks at the microphone describing “prison abolition” as unrealistic, as detracting from the rest of the action statement; voices spoke of prison abolition dismissively, as if it was one the most ridiculous things they had ever heard. I remember thinking, “No, I’m pretty sure that’s a thing.” And I was intrigued that in a room of committed Unitarian Universalists—and let’s be honest that many of us think of ourselves as unusually informed and open-minded—that so many people seemed not only unable to imagine what a prison abolition movement might look like, but were also unaware that many social justice activists (including many UUs) have been thinking for a long time about how another world is possible in regard to criminal justice.

In general, the debate about prison abolition starts to look and feel a lot different depending on your social location: how many people you know and love who have been a part of the prison industrial-complex or whether you yourself have been. From the perspective of someone caught up in the web of our current mass incarceration system, the chant from the activist Assata Shakur—of wanting to abolish the current system—starts to make more sense:

It is our duty to fight for our freedom.

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and support each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains. (Dubler and Lloyd 198)

This chant is often heard at #BlackLivesMatter actions. It also echos a famous slogan of Karl Marx: “Workers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains!“

Fast-forwarding five years to June 2020, to last year’s UU General Assembly, the gathered delegates passed an Action of Immediate Witness on “400 Years of White Supremacist Colonialism,” which included a line calling on UUs to “adopt a vision of prison abolition.” Keep in mind that this past summer’s General Assembly happened about a month after the horrifying viral video of George Floyd being murdered by a white police officer, who knelt on his neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. Also in response to George Floyd’s murder, our current UUA President, The Rev. Dr. Susan Frederick Gray, released a statement that said, “We must demilitarize and defund the police. We must defund and decarcerate the jails.”

The General Assembly debate in 2015 planted the seed in me that there was failure of imagination in some parts of the progressive movement regarding how to end mass incarceration. But it was Susan’s leadership that June that made me realize, “Ok, we’re doing this”—and motivated me to schedule this post as part of my own work to more fully to imagine that on the other side of our current carceral state, another world is possible.

Now, I realize that this topic may be challenging for some of you. It’s challenging for me. There is no one right way to respond to the social problem of “mass criminalization” and “hyperincarceration.” And I invite you to consider that you may find yourself on different points along a spectrum that could range anywhere from some reform on one side to more radical abolition on the other side:

- No change – keep the status quo of mass incarceration

- Abolish the Death Penalty – commute to life in prison

- Some decrease in prison population

- Significantly decrease (>50%)

- Abolish Prisons to the greatest extent possible

I’ll briefly address each one in turn.

To start with the status quo, I hope that the dire statistics I have already shared have convinced most, if not all of you, that we can and must do better than either maintaining or increasing our current state of “mass criminalization” and “hyperincarceration” (Dubler and Lloyd 18).

To start with the status quo, I hope that the dire statistics I have already shared have convinced most, if not all of you, that we can and must do better than either maintaining or increasing our current state of “mass criminalization” and “hyperincarceration” (Dubler and Lloyd 18).

So let me turn to the question of where you may find yourself on the above spectrum, which introduces a related abolitionist movement: “abolishing the death penalty”—that generally begins with a call to commute all death sentences to life in prison. Until recently, I didn’t plan to bring up the death penalty. I’ve posted previously on capital punishment, and I’ll have to limit myself to only a few urgent points in this current post.

Here’s what changed my mind about bringing up the death penalty. As some of you may have been following, prior to the past few months, the last time the United States government executed someone was 2003. The most recent execution was 8 days ago, on January 16, 2021, four days prior to the end of Donald Trump’s term as President. And I invite you to hear just the opening paragraph from the dissent of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor:

After seventeen years without a single federal execution, the Government has executed twelve people since July. They are Daniel Lee, Wesley Purkey, Dustin Honken, Lezmond Mitchell, Keith Nelson, William LeCroy Jr., Christopher Vialva, Orlando Hall, Brandon Bernard, Alfred Bourgeois, Lisa Montgomery, and, just last night, Corey Johnson. Today, Dustin Higgs will become the thirteenth. To put that in historical context, the Federal Government will have executed more than three times as many people in the last six months than it had in the previous six decades.

And as Justice Sotomayor concluded in her dissent, these executions were rushed: “[They] received inadequate scrutiny, without resolving the serious claims the condemned individuals raised. Those whom the Government executed during this endeavor deserved more from this Court.”

To transition from the possibility of abolishing the death penalty to the midpoint on the spectrum of beginning to reduce the numbers of people imprisoned, one key quote that comes to mind is from Bryan Stevenson’s powerful book Just Mercy, which has recently been made into a film: “Each of Us Is More Than the Worst Thing We’ve Ever Done.”

Along those lines, the most commonly suggested starting point for reducing mass incarceration is releasing people who are in prison for nonviolent drug convictions. That could indeed be a good place to begin, but as Rachel Elise Barkow has detailed in her book Prisoners of Politics: Breaking the Cycle of Mass Incarceration (Harvard University Press, 2019), we also need to acknowledge that early release of nonviolent drug offenders would only account for ~15% of people imprisoned, and would not come anywhere close to making our rate of imprisonment in this country more equitable compared with other liberal democracies (13).

And even if we open our minds, hearts, spirits, and imaginations to significant reductions in people incarcerated, there remain some difficult truths to face: “Even at half its current size, the U.S. incarceration rate would remain three times that of France, four times that of Germany, and similar degrees in excess of where it was for the first three-quarters of the twentieth century” (Dubler and Lloyd 30-31).

If we are are going to make serious changes to our current system, the journalist and Yale law professor Emily Bazelon has made a strong argument in her important and accessible recent book Charged: The New Movement to Transform American Prosecution and End Mass Incarceration. She makes a persuasive case that changing the power of prosecutorial discretion could make a major difference.

In our current system, prosecutors have a huge influence in determining whether or not to authorize arrests in the first place, request bail, hold someone in jail or release them on their own recognizance, press all charges or lean toward a plea bargain. She emphasizes that, “Prosecutors decide, especially, who gets a second chance” (xvi-xxvii).

Bazelon makes a good case for beginning with a focus on prosecutors. It is also true, however, that the criminal justice system has many interlocking parts, so there is also plenty of room for reform in courts generally, parole boards, and more. And if you are curious to dive into the details, her book includes a twenty-page appendix that gets into specific details of important and potentially actionable changes (315-335).

But instead of getting lost in the details of reform, I want to invite us to venture forth one final step and experiment with opening our imaginations to some ideas of what it might really look like to abolish prisons to the greatest extent possible.

To consider viable alternatives, it can be important to realize that we need more that abolishing the prison system we have. We need to replace a toxic system (the prison industrial complex) with a better system. As the prison scholar and City University of New York Professor Ruth Wilson Gilmore (1950-) has said, “Abolition is about presence, not absence. It’s about building life-affirming institutions” (brown 1). Or, as the activist, author, and Professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Angela Davis (1944-) said in her pathbreaking 2003 book Are Prisons Obsolete?, such a shift would require, “revitalization of education at all levels, a health system that provides free physical and mental care to all, and a justice system based on reparation and reconciliation rather than retribution and vengeance” (107).

These points bring us back to where we began: the universalist movement—and the need to continue that trajectory of human rights in ever-widening circles of inclusion—to build a solid floor for all: universal health care, universal education through college (or vocational training), and a universal basic income—so that every human being can live a life with dignity.

As we seek to imagine a better world beyond locking our fellow human beings in cages, it is important to acknowledge that with the rare exception of true sociopaths, “Most violence is not just a matter of individual pathology—it is created. Poverty drives violence. Inequity drives violence. Lack of opportunity drives violence. Shame and isolation drive violence. And…violence itself drives violence” (Sered 3).

If we want to get serious about ending mass incarceration, we need to divert funding from the military-industrial complex to help fund better domestic social programs. As Dr. King told us, “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual doom.” Likewise, we need to shift funding from the prison-industrial complex to fund restorative justice programs.

Let me say just a little bit about what that means. Earlier, when we talked about the death penalty, you may recall that the name of the case in which Justice Sotomayor was dissenting was called The United States vs. Dustin John Higgs. Our current system of justice centers the government as the aggrieved party, and assigns a consequence in the form of punitive justice. But the most direct victims in this case were the three women Mr. Higgs was accused of playing a role in their murder.

I don’t want to get lost in the details of this one case; instead, I want to underscore that a restorative justice system would focus not on the government, but on either the victim of the crime (if they are still alive) or those surviving family and friends most directly impacted; it is a form of a “truth and reconciliation” process—and one that can be transformative and powerful for all involved.

I’ll give you one example of some of the main steps that are fairly representative of similar restorative justice models—and note that many of these steps are not found in our current, so-called “justice” system:

- “Acknowledging responsibility for one’s actions” – truth-telling is the requisite first step in any truth and reconciliation process (96).

- “Acknowledging the impact of one’s actions on others” – note that impact is important regardless of intent (101).

- “Expressing genuine remorse” – this step requires going to an emotionally vulnerable place beyond just “The one who does the crime does the time” (106).

- “Doing Sorry”: Taking action to repair harm to the degree possible, action guided when feasible by the people harmed (111).

- “No longer committing similar harm” (119).

Creating programs that guide people through accountable and authentic truth and reconciliation processes would potentially be so much more life-giving and transformative for all involved than simply hoping that the threat of locking someone in a cage would deter crime. Clearly, that approach alone is not working. And many of the growing number of restorative justice programs around our country have impressive statistics of their effectiveness (Sered 134).

For more specifics, one good recent book is Until We Reckon: Violence, Mass Incarceration, and a Road to Repair by Danielle Sered, who has had significant success with running a restorative justice program in New York. An even more accessible book is Healing Resistance: A Radically Different Response to Harm by Kazu Haga, who does similar work in the Bay Area.

For now, as I move toward my conclusion, let us come full circle to the third of those recent historic Wednesdays in our nation’s history. As we try to open our hearts and minds to the truth that another world is possible, I invite you to listen to these words from Amanda Gorman’s (1998 – ) powerful inaugural poem, “The Hill We Climb.” As we seek to imagine a better world beyond mass incarceration, consider her words anew:

If we merge mercy with might, and might with right, then love becomes our legacy, and change our children’s birthright.

So let us leave behind a country better than the one

We were left with every breath….

We will raise this wounded world into a wondrous one.

As we consider the possibility of more life-giving restorative justice processes, hear the words of her final stanza:

For there was always light.

If only we’re brave enough to see it.

If only we’re brave enough to be it.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles