N.B. Today’s guest post is by Judith Valente, poet, Benedictine oblate, and author of How to Live: What the Rule of St. Benedict Teaches Us About Happiness, Meaning, and Community. To read the first post in this series, click here: Anam Ċara in Verse: How Poetry Is a Soul Friend.

N.B. Today’s guest post is by Judith Valente, poet, Benedictine oblate, and author of How to Live: What the Rule of St. Benedict Teaches Us About Happiness, Meaning, and Community. To read the first post in this series, click here: Anam Ċara in Verse: How Poetry Is a Soul Friend.

Gray mist between trees

Portal we pass through en route

To new adventures

— Judith Valente

There are times when a particular moment might grasp our attention. We stop, listen, look, and look again. It might seem as if this quick revelation has interrupted the flow of time. This is a haiku moment.

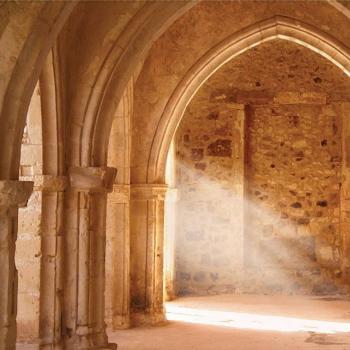

A few years ago, I traveled to the Abbey of Gethsemani outside of Louisville to report a piece for PBS-TV on the enduring legacy of the Trappist monk and writer, Thomas Merton. One of the people I interviewed was Brother Paul Quenon. Brother Paul had joined the monastic community when Merton was novice director. Merton authored more than 50 books about the spiritual life. He was also a fine poet, who continued writing poetry until his death in 1968. Merton encouraged Brother Paul to write.

When we met, Brother Paul was finishing his fourth poetry collection. He told me something that intrigued me. He said every day, he writes a haiku — as part of his meditation practice. Most of us will remember this poetic form from school. The classic Japanese haiku is usually set in nature and contains three lines, seventeen syllables — five, seven and five syllables spread across the three lines.

“In meditation, I aim for a simple awareness of the present moment,” Brother Paul told me. “My haiku is an articulation of the gift of that moment, a brief conclusion to the time spent in silence.” Because of its brevity, writing a haiku doesn’t become “just another distraction.”

As a lover and writer of poetry myself, I boldly suggested Brother Paul and I start exchanging daily haiku. It was something we did for nearly three years. Eventually, we collected our little treasures, added brief three-paragraph reflections to accompany them, and gathered them in a book called The Art of Pausing: Meditations for the Overworked and Overwhelmed.

As a lover and writer of poetry myself, I boldly suggested Brother Paul and I start exchanging daily haiku. It was something we did for nearly three years. Eventually, we collected our little treasures, added brief three-paragraph reflections to accompany them, and gathered them in a book called The Art of Pausing: Meditations for the Overworked and Overwhelmed.

We don’t exchange as often as before, but writing the humble haiku is still an important part of both of our efforts to live more attentively. For those of us seeking to slow down amid the tyranny of Twitter, the stress of the daily commute, the distractions and demands of work and family, haiku moments provide pauses written on our days. They are like the stops African tribesmen make on safari. They pause periodically to listen to the beating of the heart. They say they are trying to let their souls catch up with them on the journey.

Sooner or later, we all have to let our souls catch up with the rest of our lives.

When guiding retreats on ‘The Art of Pausing,” I often ask those attending to recall a sacred or transcendent moment they experienced in the last 24 or 48 hours – a time when they felt part of something larger than themselves. Inevitably, someone speaks up to say they have suffered from “poetry anxiety” since their school days and there is no way they are going to attempt to write even a three-line poem. That person usually ends up writing one the best haiku in the group.

Here is a haiku written by someone who insisted she couldn’t write one:

Rule of Silence

To speak in few words

In the right voice, right tone

Of things necessary

Modern haiku writers take various liberties with the form – there is even one famous haiku that consists of just one word: Tundra. I think that makes writing them all the more fun. Brother Paul and I are very different writers. His haiku are honed by years of practicing patient contemplation. Mine are often dashed off on scraps of paper during my busy work day. His might resemble a delicate water color. Mine are like black and white photos of my day.

Still, whenever I write my three lines, I come away with a better sense of having lived my day. Brother Paul beautifully captured both the quickness and the leisure of the “haiku mind” in one of his poems:

I’ve nothing to do

So I’ll get down to nothing

Expeditiously

I encourage you to get reacquainted with this most companionable of poetic forms. Maybe find a partner with whom to exchange a daily haiku, creating your own personal haiku community. These slender threads of experience lead us toward what T.S. Eliot called “the still point” of the mind and in that place, we dance.

Judith Valente is a journalist, retreat leader, poet and author. Her newest book is How to Live: What the Rule of St. Benedict Teaches Us About Happiness, Meaning, and Community. Her poetry collections include Inventing An Alphabet and Discovering Moons. She is the co-editor of Twenty Poems to Nourish Your Soul and co-author of The Art of Pausing with Br. Paul Quenon. She is also the author of Atchison Blue: A Search for Silence, a Spiritual Home, and a Living Faith. Visit her online at www.judithvalente.com.

Judith Valente is a journalist, retreat leader, poet and author. Her newest book is How to Live: What the Rule of St. Benedict Teaches Us About Happiness, Meaning, and Community. Her poetry collections include Inventing An Alphabet and Discovering Moons. She is the co-editor of Twenty Poems to Nourish Your Soul and co-author of The Art of Pausing with Br. Paul Quenon. She is also the author of Atchison Blue: A Search for Silence, a Spiritual Home, and a Living Faith. Visit her online at www.judithvalente.com.

Brother Paul Quenon, OCSO is the author of several volumes of poetry including Unquiet Vigil: New and Selected Poems. His newest book is In Praise of the Useless Life: A Monk’s Memoir.

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.