Spirituality — at least, the kind of spirituality that is anchored in a relationship with God — has two essential movements: God’s initiative, and our response. As the 1st letter of John puts it, “We love because God first loved us.” God’s “first love” is the first movement of the spiritual life, and our responsive love — not only toward God, but toward our fellow human beings — is the second movement of the spiritual life.

In the monastic world, God’s first movement of love is seen as a gift: the charism that defines the spiritual life. The second movement of love — the way we human beings respond to the gift of God’s love in our lives — is our spiritual practice. It’s practice in the sense that a doctor practices medicine: it’s not a rehearsal, it’s the real thing, but likewise it’s not theory, it’s the action or actions done to respond to that freely given love.

Therefore, when we talk about spirituality, naturally we are talking about “what we do” to make our spirituality real, to embody it as an essential part of our lives. And different faith traditions naturally have different practices: for an obvious example, Catholics pray the rosary while Muslims fast during Ramadan. There’s plenty of overlap between the spiritual practices of different faiths, but also plenty of uniqueness as well. So it only stands to reason that people who are open to interfaith relationships can and do find meaning by discovering the spiritual practices of faiths other than our own.

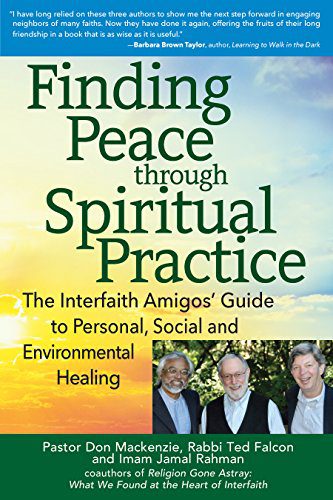

This is the basic premise behind a wonderful book, Finding Peace through Spiritual Practice: The Interfaith Amigos’ Guide to Personal, Social, and Environmental Healing published last year by Skylight Paths. It is the third book by the “Interfaith Amigos” — Pastor Don Mackenzie, Rabbi Ted Falcon, and Imam Jamal Rahman. These three clergy persons from the three Abrahamic faith traditions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) became friends in the aftermath of 9/11, and have devoted much time sense then to foster their message that healing comes through friendship and understanding — particularly between and among the different faith traditions.

I love this book not only because it has such a positive message, but because it is a veritable catalog of spiritual practices from each of the three Abrahamic faiths. Some of the practices are long-standing, core spiritual exercises, while others are newer expressions of faith, some even original to the Three Amigos themselves. The final chapter of the book, “Making Spiritual Practice a Way of Life,” is especially useful, since it surveys a variety of practices for daily use, for marking the rhythm of the year, and honoring the important passages over the lifespan, for each of the faiths. That chapter feels like a handy, “Cliff Notes” summary of the key spiritual practices essential for an intentional, faithful live, as expressed in each tradition. Whether you are anchored in one religion and simply want to learn about the other faiths, or are seeking to expand your own personal spiritual practice by exploring exercises from traditions other than your home faith, this is an excellent guide.

But of course, this book if more than just a catalog of cool spiritual things to do. The authors speak clearly that these practices are transformational — they have the power to change the person who embraces them. As the book’s subtitle implies, spiritual practices such as the ones surveyed in this book have the power to bring healing, not only to us as individuals but to our communities and even to the world at large.

Given our current political and social climate, I think we all recognize that we live in a world desperate for deep spiritual healing! Thankfully, the Interfaith Amigos have real, practical solutions to offer.

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.