Strong structure, bold statement, clear line, and yes or no. A good divination session is about form, not content. Let’s see what I mean.

In my cartomancy classes I don’t teach lists of meanings. I don’t do it simply because I prefer to think about what catches my eye when I look at a picture. I start with this question: What’s interesting here? How does this work? – and by this I mean, how does composition work? A good visual composition grabs you by the heart and is unforgettable.

So with the divination act, which is very much a mirror of the visual text in front of you. That is to say, a good divination session with cards is unforgettable because reading the images right hits the nerve that responds to what is obvious to the unconscious mind. The conscious mind responds to clichés because it’s safe, because it learnt what is culturally appropriate – everyone weeps at a wedding – but the unconscious mind responds to truth, taboo, and bold statements. Imagine a wedding ceremony that’s beyond the cliché. I haven’t seen one yet, for all the planning and the formal preparation that goes into it…

The strong structure

Although all divination with the cards is an interpretative art, the skill that goes into it is no different than what we do when we perform a picture analysis, and when we know unambiguously why an image works and why another doesn’t. Why do some pictures come across flat and boring? Why are others dynamic, full of depth and contrast, and thus able to grab you by the heart?

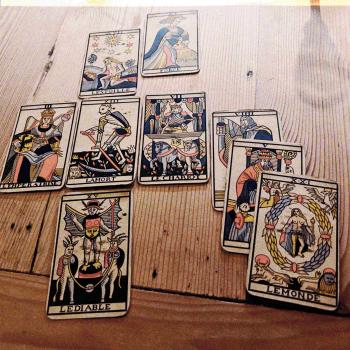

A good visual text is good simply because it has a solid structure. A solid structure is not ‘many things, nor is it ‘all over the place’. When you look at the cards that present you with symmetrical duos and trios, what you respond to is not the cliché: ‘Here’s the Devil and here’s the Pope, each performing their devilish and dogmatic duty, and that means something.’ What you respond to is a correlation factor that’s anchored in a clearly recognizable cultural context.

If you say to someone, ‘first the wedding and then hell’ – upon seeing the cards of the Pope and the Devil – what you’re pointing to is not an inherent meaning that the cards supposedly possess, but rather, a situational positioning. Culturally speaking, it’s better to be blessed by the Pope than cursed by the Devil.

The latter can seem attractive to some, but it will never work in a culturally consecrated context. Try telling everybody that the Devil officiated at your wedding ceremony, and see how far you get with acceptance. The Wiccans in the 60s and 70s notoriously did that, but all they achieved was a whole lot of noise and newspaper headlines that ultimately led to divorce; divorce from society and internal strife. A lot of devotees would later split with their covens, the Devil, the high priests, and the drama, retiring also from the general public eye.

Some graphically explicit stories make it into a text, contributing to the creation of great literature. But just as is the case with images, what makes a literary text good is not the fluff and the amount of descriptive detail that goes into it. Rather, what makes a literary text good is a solid structure and a bold outline that makes an unambiguous statement. Even poetry that operates with a highly ambiguous content must hit the nerve of the obvious if it’s to succeed. If it’s merely ambiguous, poetry falls into forgetfulness faster than your scrolling on the internet.

As a literature professor I used to teach students about how to look for the strong statement at both the visual and verbal level in a text. As a cartomancy teacher I do the same: I say, ‘look at this picture or a string of pictures together and ask yourself why it works, why it enables you to say bold things, unheard of things, and things of substance that touch the heart.’ The answer, ‘it works because it worked for other diviners in the past and I’m working within that lineage’ is not a good answer. An answer like that relies on imitation, on rendering a flat image of what is otherwise plain and obvious, staring you in the face.

I’ve written plenty about what divination is not about, and why I associate my practice with the discipline of paying attention, calling what I perform martial arts cartomancy. But here I want to insist on truncating it even more. So let’s look at a few fundamental principles again.

It’s not about lists and decks

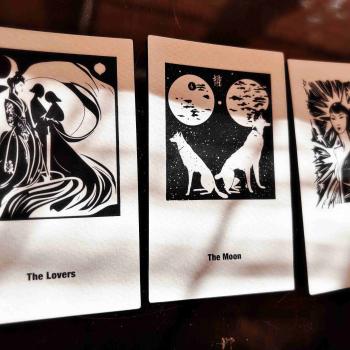

It’s not about what set of cards you use: This is modern, this is antiquated, this is cool, this is art, this is occult, this is witchy, this is esoteric, this is literal, this is fortunetelling, this is Marseille, this is Rider Waite. It’s about giving even the most trivial of questions a strong backbone and structure.

What goes for life, goes for reading cards: form, balance, boldness, and uniqueness.

Lists of meanings, charts and correspondences have nothing to do with a sitter’s hopes and fears, but everything to do with the reader’s hopes and fears. Are you beyond yours yet? If not, ask yourself why. How are you going to be bold, unique, balanced, and nuanced in your readings, if you’re fearful of how the other you read the cards for may respond, or if you’re hopeful that what you say is relatable? Marketing and commerce works with exploiting people’s hopes and fears. What you’re doing is divine for beyond the cliché. Lists of meanings may seem like a treasured vault or safety-net, but all they ever do is lock you in the world of clichés.

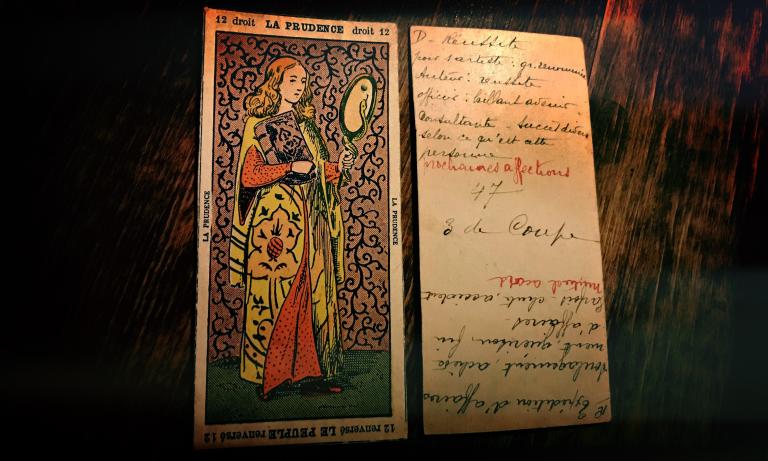

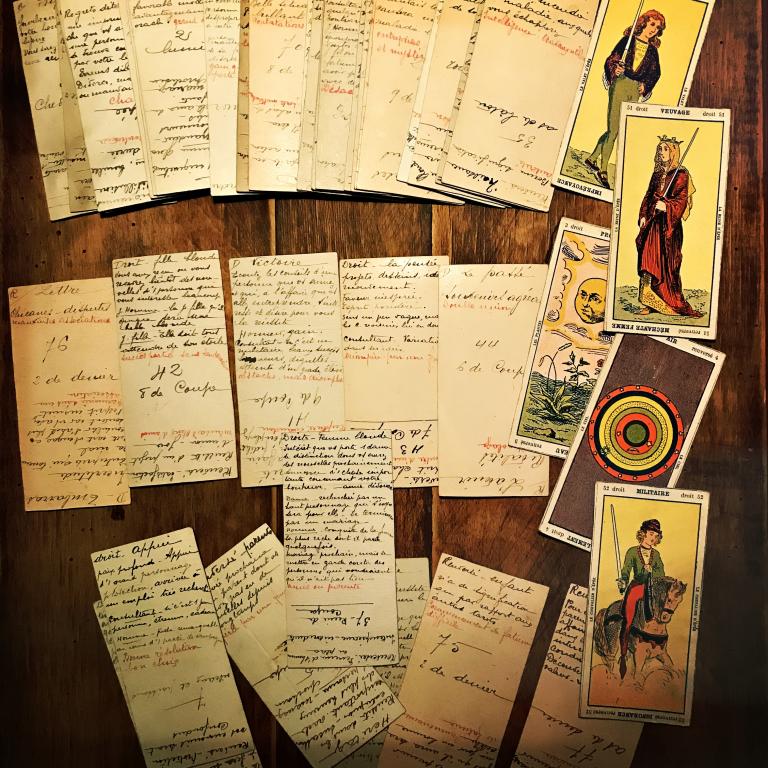

Sometimes I think about writing a straight book of meanings based on the scribblings that other diviners before me did on the backs of their cards. I have many old decks that feature both, borrowed meanings and personal wisdom, duly handwritten on the back of each card. If I wrote that book, I could at least claim that my sources are solid and beyond any further speculation.

Look at this old Etteilla inspired deck from the late 1800s. I got it solely because of the ink and the quirky handwriting. As to the rendered meanings, let us not even go there, as it’s all flat, flat, flat, cliché after cliché. I prefer to think of this diviner being smarter than her own scribblings, offering advice in accordance with seeing what’s appropriate for each individual situation, meaning, seeing the obvious under her nose rather than going with what others before her have decided is the case.

As far as I’m concerned, if I can’t explain to myself why the presence of three queens in a string of cards on the table means trouble, then all I ever do is repeat what is potentially ridiculous at the level of common sense.

Rarely, if ever, do the books that promise to uncover some secret meanings tell you where what is taken for granted comes from, that is to say, what rationale informs the charts and categories. I can imagine why three women together can lead to gossip, and hence trouble, and I can also understand why three women together is potentially worse than the situation when only two are together, ping-pong’ing their own experiences to one another and forgetting about third party issues.

But I will have a very hard time explaining it to myself why coins relate to the bones and the swords to the air. Is it because we tend to stash the coins inside our skin, as it were, and we wield the swords in the air? I can think of a certain holy cup that’s been hidden from sight – though some templars are now revealing the secret that what we call the holy grail has been staring us in the face, it’s Mary Magdalene herself, or an inscription tomb in England, or Normandy, depending on who you’re asking. As for the swords cutting through the air, why is that so special? Weren’t batons trees once, growing tall and cutting through the air too?

My question to you is this: Is the knowledge that lacks explanatory depth good knowledge? The illusion of knowledge is worse than ignorance, which means that getting the fundamentals straight and leaning on a solid structure of seeing is not only desirable but ultimately obligatory.

It’s not about the sitter’s problem

It’s not about the subject either, or what a sitter puts on your table in terms of hopes and fears or concerns. It’s about distinguishing between the shades of grey. What’s essential in her question and what is not? Can you see the underlying structure of what a person is asking? Some pose very involved questions that don’t even have anything to do with what they present as a problem. How do you rise to what you actually know about what you’re doing, remembering also that staying uninvolved and detached is where compassion and clarity reside?

It’s not sure that the sitter is clear in her own head about her issues. If she was, she wouldn’t be sitting with you. The sitter is there to create a structure around your divination. She may have a story of her own life to tell, but getting that story is not the purpose of divination. The sitter comes to you for your story of the structure that she gives you.

What might look like a lost love story is really only interesting because, looked at it from another angle, it may easily turn out to be winning a ticket to a grand cruise through paradise. First the wedding…

The actual subject of a life-story is as meaningless as the lists of meanings that you find even in the best fortunetelling book. What’s meaningful is the way you look at the underlying structure of what’s being put on your table. How bold is the outline? A reader who possesses clarity is able to see more than ’emerging patterns’. She can see the obvious.

The structure of your divination must be bold enough and plenty astonishing, as that’s the only way in which you can grab the sitter’s attention on all levels, beginning with the heart, the conscious and the unconscious, and all the ensuing ‘ahs’ and ‘ohs’. If the structure of your divination is not obvious beyond the cliché, the sitter won’t go home with a memorable impression.

It’s not multiple choice

It’s either this or that. Either he still loves her or he doesn’t. Anything else in between is already using too many words. Too many words destroy the obvious.

Too many words give the sitter an excuse to get distracted from the strong message. Why would you let her leave your parlor with a weak message? Because it’s safer? Safer for whom?

Your sharp cut must be in the sitter’s face. You don’t negotiate with the punchline. You either laugh or you cry. You don’t sit there with an unfinished story. ‘But the Lovers card means love, or choosing what I love…’ No, it doesn’t. What you want to know determines the meaning of the card. Why you want to know lends dynamics to this meaning.

If the Tower follows the Charioteer and we have the card of Judgment in the last position, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the situation will improve, that you rise again to a new experience. When you crash, you crash. There’s an announcement about it. That’s the obvious. What’s not obvious at all is the wishful thinking that goes into it. Maybe, just maybe the ones at the cemetery sharing your grave can collectively give you a push from the hereafter, but does being pushed mean an improved situation?

How often do you tell your sitters, upon seeing Judgment following the Tower or some other nasty card, that ‘the situation will improve’? How do you know that? In olden times being lucky simply meant having power. When you’re crushed you don’t have any power. You’re at the mercy. It’s this mercy that determines where you’re going, or where your sitter is going, not your illusion of control. Admitting that you’re subject to conditions beyond your luck is more empowering than self-empowerment via a strong wish.

Formalist art

To sum up, divination is about paying attention to form, elements such as balance, tension, color, lines, light, speed, space, agency, and function.

You can have access to the collective wisdom and repository of knowledge of the diviners that came before you, or the ones you compete with, but having access doesn’t automatically mean that you actually know yourself what you’re talking about. The only way in which you can know that is if you take the time it takes to look at the structure that three or more cards together forms, so you can understand it beyond the illusion of knowing, beyond cliché and good memory.

If you want your readings raised to the power of art, then make an effort to understand the basic principles that constitute the formal composition of a divination session – from the question to the visuals of the image, including what the gestures and the body language of the sitter tell you. Or decide that, on occasion, you might actually want to take a break from reading books of meanings, and pick up instead books of fundamentals. What is Not features this ext here in expanded form, and you’re also welcome to 21+1 Fortune-teller’s Rules.

♠

For more such practice with the cards:

- Join the Read like the Devil Club.

- Visit also Aradia Academy and sign up for the newsletter that will keep you informed on upcoming courses and cartomantic activities. Note the Off the Shelf offering that also includes free resources.

- Check out my books on the philosophy and practice of divination at EyeCorner Press.

- Get a reading. When I perform a reading, I also teach, simply because I can’t help myself, so you will be twice served.