We live in a world of representations. We transact with the notion of a ‘self’ against ‘the other.’ A zen inclined person is able to maintain the fixity of such social constructs, while at the same time know that they are precisely that, social constructs.

Part of what I like about my work as a fortuneteller is seeing how we cope with the perennial question of the self in relation and the point when the idea of taking everything personally breaks down. I’m after that point, because recognizing the flow of events in the proposition that life happens as it happens features absolutely no constructs of separation: I against the other, mother against daughter, friend against enemy, groups marked by identity against governments.

There are many questions to pose when divisions and separations are maintained. There are no questions to pose when the point of break down of social constructs occur. The first thing that goes out with the rubble is precisely representation. It’s a tough one to handle, because we all want recognition. We want recognition for what we do, and we want recognition of our boundaries.

If the neighbor parks their car on my property because it’s convenient for them, and hey, there’s so much space I enjoy over here, you can be sure that I’ll react. The fact that I have more space than the other is besides the point, and none of the other’s business. What I want is not a false correlation about what I own and why – I don’t even owe any explanations for that – but a simple recognition of my jurisdiction. The whole legal system is built around policing the self in relation.

The same applies to work. I read the cards for people who ask about how to deal with the situation when they present an original idea at work, only to see other colleagues run off with it without crediting.

As it happens, cards for divination have been invented to address precisely such situations, when the dividing line between taking liberties and maintaining boundaries is blurred.

In all my divination books and cartomancy courses, I dedicate entire sections and sessions to the art of the question, the gist of it being that it’s a good idea to identify first what is at stake in a question, and then proceed to analysis and judgment. As questions can assume different characters – such as the descriptive, the analytical, the reflective, and the evaluative – they can also change nuance, all according to how the shifting signifiers or the representational enters into play across the board.

The question ‘does he love me’, invites to a description of the situation on the basis of which you can conclude either in the affirmative, the negative, or the maybe mode. ‘How he loves me’ invites to a reflection of modality on the basis on which I can then conclude in the evaluative: ‘he loves me like this, serving me coffee and kissing me when I expect it the least, so he’s worth keeping.’ ‘Why he loves me like he does’ invites to a reading that has an investigative character.

Let’s just say that by merely being aware of just these four types of questions we encounter commonly in our work with the cards, we get to see how entertaining fortunetelling is.

Now, what of the time when we don’t have a question to bring to the cards? Since the 60s and up until recently, when people started looking at the cards as markers of something other than a psychological process, reading cards according to their nominal quality was very popular. Knowing how ‘this means that’ settled it for many, and it still does, when we look at the popularity of reading ‘a daily’, that is to say, looking at how one card can stand as a predictive representation of how the events in a day will unfold. You can say, ‘Today I got the Hermit. This means that I’ll be off Facebook’.

In this reading of the Hermit, what I do is look at the function of what we culturally associate with the Hermit, the act of retreating from the world. This is good enough for me, but I see that there are many for whom looking at the function of things is not enough. They want ‘meaning’, as there’s ‘more’ to the cards than just straightforward function. There’s symbolic function and value, there’s story. ‘Give me that,’ the ones invested in delusions ask. So people launch in a discourse that’s purely nominally descriptive on an elastic that stretches from the commonsensical to the utterly ridiculous. Any classic little white book, the short booklet that accompanies a standard set of cards, will introduce you to a list of keywords that you can pick from, for instance these associations: the Hermit equals old age, aloneness, retreat from the world, wisdom, prudence, attention, mistrust, illness, lack of vigor, stupor, amnesia, and so on.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with such a list of words, if there’s a question on the table, but things go rotten when there’s no question. The hermit representing ten different things is a whole lot of things to equalize, so how do you determine which of the ten will turn out to represent your day? You can’t. Not if you want precision. You can only do it in hindsight: ‘Ah yes, it was all about being limited in my body, as my back hurt today, and not at all about sitting and philosophizing.’ There goes that initial insight in your ‘daily’…

I think about questions a lot, and I like to be prompted by some that are not necessarily those of my common conditioning. I’m about to start a new cycle of Tarot prompts on the topic of Seven Deadly Sins. In my cartomantic prompts what I do is turn it all around. I don’t read for the plot, for ‘meaning’, as arbitrary meanings leave me cold and not convinced. I don’t read for the pragmatic function of our cultural competence in recognizing what images represent exactly either. I read for the art of the question, when I look at the cards past conditioning. The only condition I take into account is the framing of the context. In this case now, why look at seven deadly sins? Because I see how the old representation of the thieves of our common sense is very much alive in our modern day. But if I want to address my consumerism – from food to uninformed opinions – what questions might I ask? Of the opposite representation? Of virtues?

As it happens the whole of the Tarot has been built around the representation of classical virtues, with justice, fortitude, temperance, and prudence leading the way. Always depending on context, the nominal factor here acquires significance only if we constrain the question to fit a template, a trifecta, a four-point model, or a 12-step program.

How do we ask questions that bring us to a level where we get to experience something other than a trite model? People love models, and I’m good at crafting and designing them myself for instrumental purpose, but when I want to get past representations, and get a sense of how I can better observe flow not separation, then I must find a way of asking questions that bring me to a place where I don’t operate with opposites: sins vs virtues, ‘me’ against ‘the other’.

The classicists didn’t consider the autobiographical self as part of the seven deadly sins, rather more like elevating it to the status of ultimate virtue – ‘being yourself’ is very much endorsed as a virtue – but upon reflecting on the actual construction of ‘myself,’ what can we say we find there?

I’m greedy for an answer, greed I want to impale right now with a set of cards that can prompt me towards what the question is here.

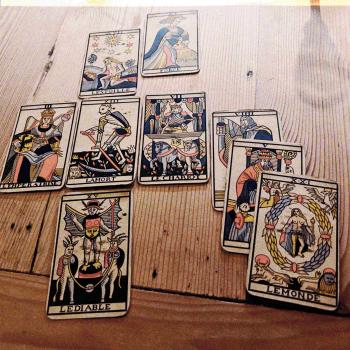

Three cards fell on the table from Elisabetta Cassari’s wonderfully disturbing deck, the Solleone Tarot:

The Queen of Coins (‘pentacles’ is not the correct translation of the Italian denari), Two of Swords, and the Chariot make an appearance for a question to arise:

In the pursuit of money, who does the Queen of Coins stab in the back? To what outcome? We don’t see her riding in the Chariot. Is the reptilian figure below the chariot her? What does this tell us about greed? Greed rides along, sometimes even virtuously, if dedication to it is strong enough. But… and meanwhile, the Pope’s finger.

In my Zen practice I’ve been schooled in the art of ‘pointing out instruction’. When this happens, what is experienced is precisely a move beyond the trite question, beyond meaning and symbolic function. We’re here with sins and virtues as part and parcel of what we’re able to recognize is the case. We read the cards for that. Nothing more, nothing less. If you’re adventurous, you can find that a snappy reading under the signature of reading like the Devil is more dangerous than all the sins and virtues in the world.

♠

Seven Deadly Sins stays open for registration until Sunday. We start Monday. I’ll be happy to welcome you on a cartomantic prompts ride.