This is my introductory post, and appropriately enough everyone on Patheos Catholic is talking about why they remain Catholic.

I’m a convert. Possibly, I’m the only person in the world who can say that she’s a Catholic because Jean Paul Sartre made her do it. Basically, I was a young atheist. I had been raised as a liberal Anglican, but when I hit the age of reason I had questions about God and about faith. The answers that I received were singularly unsatisfying, and didn’t seem to justify the inconvenience of spending a couple of hours every weekend popping up and down like a jaybird (Sit and kneel and stand, and again now, sit and kneel and stand…) and trying to amuse myself by reading sexual innuendo’s into the hymnal. So I refused to get confirmed, and committed myself instead to showing that Christians were ignorant sheep who accepted an irrational proposition for dubious psychological motives.

When I was 18, I started to realize that I was actually completely ignorant about religion, and that I had accepted a lot of irrational atheist propositions for dubious psychological motives. I had taken a philosophy course in high school, and this had introduced me to thinkers who were grappling with faith in ways that were deeper and more complex than anything I had encountered before. I read Kierkegaard, Dostoyevski, Merton, Sartre and Kant. Eventually, this heady philosophical stew boiled over and I was left with a massive existential mess where my former certainties and convictions had been.

Kant taught me that the epistemological divide between my mind and reality was more or less insurmountable. Kierkegaard showed that my belief in reason, beauty and morality was not founded on a sure and indubitable foundation but rather on a leap into the profound abyss of faith. Sartre taught me about the unbearable burdens of human freedom in a godless universe, and indoctrinated me into an absolute devotion to the virtue of authenticity. Dostoyevski revealed the practical implications – alternately dark and ridiculous – of my atheistic aestheticism. By the end of this I felt more or less like Ivan Karamozov wandering around his bedroom with an ice-pack on his head arguing with the Devil about whether the Devil exists.

Finally, Merton suggested a way out of this mess. Without resorting to platitude or superficial comfort, he offered a Christian vision of the universe that grappled seriously with its darkness and complications. Merton’s God wasn’t a stand-in for personal responsibility, a psychological placebo, or a convenient stop-gap to explain away the mysteries of reality. Merton’s God was a terrible and beautiful personality that one encountered in the darkness: a lightning flash of illumination, a burden that made all burdens light.

This God was absurdity par excellence, the unattainable Truth whose shadow played on the walls of my interior cave. But, and this was the crucial point, this inconceivable mystery knew me and wanted to be known. The philosophers had shown me beyond any doubt that it was completely beyond my capacity to cross the divide that lay between myself and Truth, but now I was presented with a Truth who was a person and who was capable of reaching across the divide between Himself and me. Moreover, this Truth had done so in the most radical possible way by becoming a human being: He had come to share in my humanity so that I might share in His divinity.

Confronted with the truth about what belief in God is, what it entails, and why a person might believe I realized that my atheism was a text-book case of mal fois. I was an atheist because I craved absolute autonomy, complete independence and ultimate authority over my own life. Yet none of these desires were rational or justifiable given the manifest limitations of the human condition. Fundamentally, my existentialism itself was inauthentic. So being a good existentialist, I had no option but to honestly investigate the God hypothesis in good faith.

My approach was simple and experimental: if there really was a being on the other side of the chasm, and that being really did want to be known, then surely if I asked Him to reveal Himself He would. That followed. So I started to pray as an agnostic, asking whoever was out there, if he/she/it existed, to reveal him/her/itself. Within three months, I was completely convinced that I had my answer and that I was being called to join the Catholic Church.

So that’s how it began. But it still leaves open the question: fifteen years later, am I still happy with this decision? Have any new questions emerged? What has challenged my faith? And why am I still a Catholic today?

Next: Ante Up, Pascal!

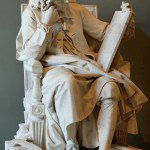

Photo credit: Melinda Selmys