Yesterday I read a comment by 3vil5triker on my post Is Heaven for Real? My response ended up being much longer than comment length, so here it is.

3vil5triker writes:

How come the original accounts, and the beliefs that derive from them, are not subject to the same kind of skeptical inquiry?Can you really say that the early church accounts and assurances of heaven were not bolstered and encouraged by similar financial, societal and religious incentives of the time?

And here’s the kicker, what if one of those heaven tourism books, lets say one authored by a member of the priesthood relating his near death experience who then goes on to become canonized as a saint, receives the Church stamp of approval, would you still have the same misgivings?

Just poking at your brain a little.

Okay, so the last paragraph is the easiest to answer. Basically, you’re talking about a situation where an adult has a private revelation as a result of a near death experience, and it is investigated by the Church and deemed to be in accord with faith. The two most salient differences between a situation like this and that of a child like Burpo are:

- Adults are not as easily suggestible as children, and they are less vulnerable (though obviously not completely invulnerable) to exploitation. So I don’t have the same moral reservations that I have with a child.

- There has been a process, usually a fairly extensive one, of vetting and investigating the situation conducted by an external authority. The Vatican routinely rejects supposed miracles and apparitions. This means that at least you’re not going to be dealing with a blatant hoax.

Now, that said, I’m basically agnostic about private revelations — including those that have been approved by the Church. No Catholic is required to believe the contents of an approved revelation — approval just means that believing it won’t harm your faith. It doesn’t make it part of the canon.

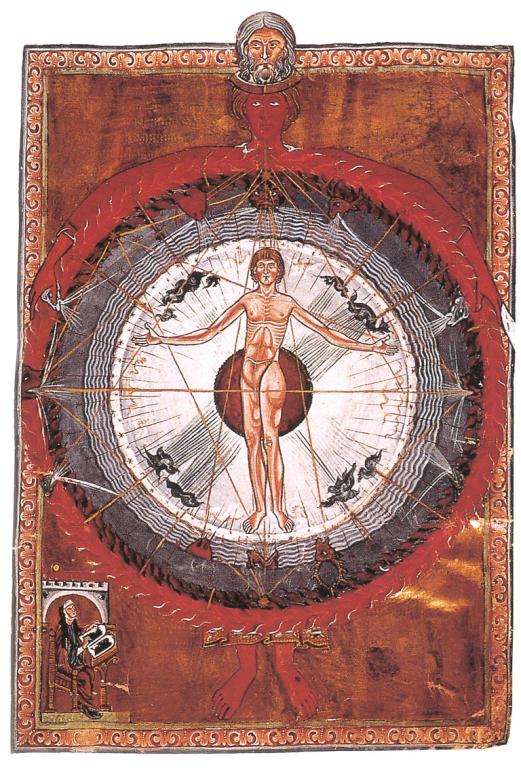

To be honest, I’m not a huge fan of private revelations generally. It’s rare that I see one that really resonates with me. Hildegard of Bingen’s visions of the cosmic egg come the closest — but at least in part that’s because they’re so obviously speaking the language of myth and symbol that nobody could possibly imagine them to be a literal portrait of an actual thing or event.

Personally, I think private revelations, visions and the like are manifestations of some power outside of the conscious self delivering to consciousness a series of images, locutions, what have you, that are deeply personally meaningful and which convey some kind of important spiritual insight. Whether the active principle is the subconscious, or the Holy Spirit, or some other spiritual being (a guardian angel, e. g.), or some combination of the above I don’t pretend to know.

Definitely they sometimes have the quality of intuition, revealing things that could not be known through logical processes — but again, the question of whether intuition is a genuine revelation from outside the self, or a manifestation of the unconscious mind putting together information that the conscious self is unaware of remains unknown. Both of theses are ultimately just models for explaining a poorly understood phenomenon using different foundational axioms.

In any case, it’s clear enough that in so far as God reveals Himself in these experiences it is generally grace acting through nature. The store of images and ideas are always concordant with the time and place of the visionary. So while people might opine that when St. John sees locusts come out of the smoke and descend to earth with a sting like a scorpion (cf. Rev 9:3), he’s really seeing modern stealth fighters, the fact is he describes locusts. Medieval visionaries see visions of heaven and hell that are chock full of imagery taken from contemporaneous art — but which most people now find somewhat cartoonish.

Meaning, if God is communicating He is interacting with the imagination, drawing on familiar imagery, in much the same way that when He speaks to a person He uses language that is known to them. But as to the question of whether this involves a direct divine intervention, or just the mind itself in a state of prayer perceiving spiritual realities through symbolic language, I don’t know.

To a certain degree, I’m not even sure that the distinction can be made, or that its a real distinction: I live and move and have my being in God, and He dwells in me. Or, as St. John of the Cross says, love transforms the lover into the beloved one. So ideally, the goal of the spiritual life is for that distinction between the self and God to dwindle as you become conformed to the image of God — as love becomes your innermost truth.

As far as the possibility of financial reasons, power, desire for fame, etc. influencing people in the early Church — yes, of course it did. Scripture itself records this. I don’t believe in the Bible on the strength of the integrity of the human authors — some of them are blatant propagandists. Others are just men with normal human type weaknesses. Christ Himself notes that Moses gerrymandered the law on divorce because of pressure from his people.

What I think Scripture records is the story of a group of humans coming to know God, through their humanity and their human limitations, and also God, reciprocating by offering graces, working on individual hearts, working in history. It’s a portrait of the spiritual life, both that of the individual and also that of the community. Christ is the culmination of this, as God’s self-revelation. But then, after He returns to the Father, we’re left again with humans trying to make sense of things — but this time not as a single people, but as an ecclesia. The difference being that the encounter between the Jews and God always involved trying to make the Creator of the universe into a parochial war deity — whereas the Church (however much we struggle with this in practice) is supposed to be universal.

So my faith is not, at any point, predicated on the words or experience or claims of any one single person — with the exception of Christ. As far as He’s concerned, I think ascribing base motives to Him is just… I don’t know. It seemed tasteless to me, even when I was an atheist. I accept things He says because I trust Him. I accept the authority of the Church because I think several billion people striving communally towards truth through history as part of a continuous tradition are more likely to be right than me trying to get there all on my own efforts. But I don’t believe anything just on the basis of dreams and visions, because those can mean anything.

Image credit: Hildegard von Bingen, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47047

Stay in touch! Like Catholic Authenticity on Facebook: