For your spiritual edification

here is a selection from the public domain work

on the nature of Christ and his Church

which are both human and divine.

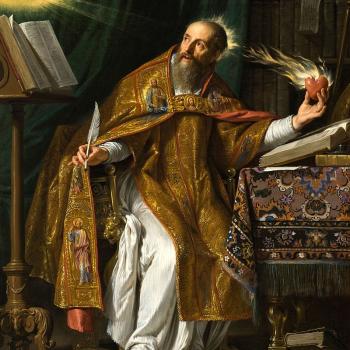

JESUS CHRIST, GOD AND MAN

I and My Father are one. — JOHN X. 30.

My Father is greater than I. — JOHN XIV. 20.

The mysteries of the Church,

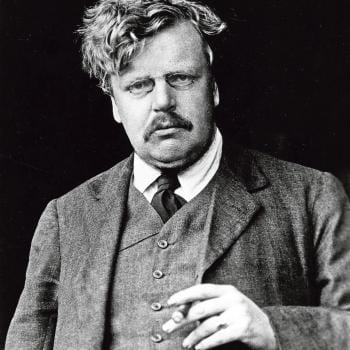

a materialistic scientist once announced to an astonished world, are child’s play compared with the mysteries of nature.* He was completely wrong, of course, yet there was every excuse for his mistake. For, as he himself tells us in effect, he found everywhere in that created nature which he knew so well, anomaly piled on anomaly and paradox on paradox, and he knew no more of theology than its simpler and more explicit statements.

We can be certain therefore — we who understand that the mysteries of nature are, after all, within the limited circle of created life, while the mysteries of grace run up into the supreme Mystery of the eternal and uncreated Life of God — we can be certain that, if nature is mysterious and paradoxical, grace will be incalculably more mysterious. For every paradox in the world of matter, in whose environment our bodies are confined, we shall find a hundred in that atmosphere of spirit in which our spirits breathe and move –those spirits of ours which, themselves, paradoxically enough, are forced to energize under material limitations.

We need look no further,

then, to find these mysteries than to that tiny mirror of the Supernatural which we call our self, to that little thread of experience which we name the “spiritual life.” How is it, for example, that while in one mood our religion is the lamp of our shadowy existence, in another it is the single dark spot upon a world of pleasure — in one mood the single thing that makes life worth living at all, and in another the one obstacle to our contentment? What are those sorrowful and joyful mysteries of human life, mutually contradictory yet together resultant (as in the Rosary itself) in others that are glorious? Turn to that master passion that underlies these mysteries — the passion that is called love — and see if there be anything more inexplicable than such an explanation. What is this passion, then, that turns joy to sorrow and sorrow to joy — this motive that drives a man to lose his life that he may save it, that turns bitter to sweet and makes the cross but a light yoke after all, that causes him to find his centre outside his own circle, and to please himself best by depriving himself of pleasure? What is that power that so often fills us with delights before we have begun to labour, and rewards our labour with the darkness of dereliction?

If our interior life, then, is full of paradox and apparent contradiction — and there is no soul that has made any progress that does not find it so — we should naturally expect that the Divine Life of Jesus Christ on earth, which is the central Objective Light of the World reflected in ourselves, should be full of yet more amazing anomalies.

The Paradoxes of Jesus

Here is He Who came to soothe men’s sorrows and to give rest to the weary, He Who offers a sweet yoke and a light burden, telling them that no man can be His disciple who will not take up the heaviest of all burdens and follow Him uphill. Here is one, the Physician of souls and bodies, Who went about doing good, Who set the example of activity in God’s service, pronouncing the silent passivity of Mary as the better part that shall not be taken away from her. Here at one moment He turns with the light of battle in His eyes, bidding His friends who have not swords to sell their cloaks and buy them; and at another bids those swords to be sheathed, since His Kingdom is not of this world. Here is the Peacemaker, at one time pronouncing His benediction on those who make peace, and at another crying that He came to bring not peace but a sword. Here is He Who names as blessed those that mourn bidding His disciples to rejoice and be exceeding glad. Was there ever such a Paradox, such perplexity, and such problems? In His Person and His teaching alike there seems no rest and no solution — What think ye of Christ? Whose Son is He?

The Catholic teaching alone, of course, offers a key to these questions; yet it is a key that is itself, like all keys, as complicated as the wards which it alone can unlock. Heretic after heretic has sought for simplification, and heretic after heretic has therefore come to confusion. Christ is God, cried the Docetic; therefore cut out from the Gospels all that speaks of the reality of His Manhood! God cannot bleed and suffer and die; God cannot weary; God cannot feel the sorrows of man. Christ is Man, cries the modern critic; therefore tear out from the Gospels His Virgin Birth and His Resurrection! For none but a Catholic can receive the Gospels as they were written; none but a man who believes that Christ is both God and Man, who is content to believe that and to bow before the Paradox of paradoxes that we call the Incarnation, to accept the blinding mystery that Infinite and Finite Natures were united in one Person, that the Eternal expresses Himself in Time, and that the Uncreated Creator united to Himself Creation — none but a Catholic, in a word, can meet, without exception, the mysterious phenomena of Christ’s Life.

The Paradoxes of Humans

If we were but irrational beasts, we could be as happy as the beasts; if we were but discarnate spirits that look on God, the joy of the angels would be ours. Yet if we assume either of these two truths as if it were the only truth, we come certainly to confusion. If we live as the beasts, we cannot sink to their contentment, for our immortal part will not let us be; if we neglect or dispute the rightful claims of the body, that very outraged body drags our immortal spirit down. The acceptance of the two natures of Christ alone solves the problems of the Gospel; the acceptance of the two parts of our own nature alone enables us to live as God intends. Our spiritual and physical moods, then, rise and fall as the one side or the other gains the upper hand: now our religion is a burden to the flesh, now it is the exercise in which our soul delights; now it is the one thing that makes life worth living, now the one thing that checks our enjoyment of life. These moods alternate, inevitably and irresistibly, according as we allow the balance of our parts to be disturbed and set swaying. And so, ultimately, there is reserved for us the joy neither of beasts nor of angels, but the joy of humanity. We are higher than the one, we are lower than the other, that we may be crowned by Him Who in that same Humanity sits on the Throne of God.

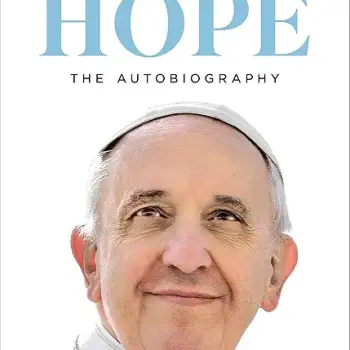

The Paradoxes of the Church

Now the Catholic Church is an extension of the Incarnation. She too (though, as we shall see, the parallel is not perfect) has her Divine and Human Nature, which alone can account for the paradoxes of her history; and these paradoxes are either predicted by Christ — asserted, that is, as part of His spiritual teaching — or actually manifested in His own life. (We may take them as symbolised, so to speak, in those words of our Lord to St. Peter in which He first commends him as a man inspired by God and then, almost simultaneously, rebukes him as one who can rise no further than an earthly ideal at the best.)

Just as we have already imagined a well-disposed inquirer approaching for the first time the problems of the Gospel, so let us now again imagine such a man, in whom the dawn of faith has begun, encountering the record of Catholicism.

At first all seems to him Divine. He sees, for example, how singularly unique she is, how unlike to all other human societies. Other societies depend for their very existence upon a congenial human environment; she flourishes in the most uncongenial. Other societies have their day and pass down to dissolution and corruption; she alone knows no corruption. Other dynasties rise and fall; the dynasty of Peter the Fisherman remains unmoved. Other causes wax and wane with the worldly influence which they can command; she is usually most effective when her earthly interest is at the lowest ebb.

Another man approaches the record of Catholicism from the opposite direction. To him she is a human society and nothing more. Of course the Catholic Church is Human. She consists of fallible men, and her Humanity is not even safeguarded as was that of Christ against the incursions of sin. Always, therefore, there have been scandals, and always will be. Popes may betray their trust, in all human matters; priests their flocks; laymen their faith. No man is secure.

Here, then, is the Catholic answer and it is this alone that makes sense of history, as it is Catholic doctrine which alone makes sense of the Gospel record. The answer is identical in both cases alike, and it is this — that the only explanation of the phenomena of the Gospels and of Church history is that the Life which produces them is both Human and Divine.