For your spiritual edification

here is a selection from the public domain work

Miracles (1928)

by

Father Ronald A Knox

The Possibility of Miracles

There is a significant story to be found in one of the less familiar by-ways of Old Testament history. When Israel had been oppressed for seven years under the tyrannous yoke of the Midianites, God would raise up a deliverer for His people; and His choice fell upon Gedeon (sometimes spelt Gideon), a hero of little estimation, till then, in the world’s eyes; “Behold,” he says, “my family is the meanest in Manasses (sometimes spelt Manasseh), and I am the least in my father’s house.” Humility, rather than want of faith, made Gedeon ask for a sign, a miraculous sign, that this strange vocation was really meant for him. And Almighty God saw fit to indulge his request. Gedeon laid a fleece of wool on the ground, and left it there all night. The first night the fleece alone was wet with dew, when all the ground was dry; the next night, the fleece alone was dry, and there was dew on all the ground. An unfamiliar incident, and one which would hardly be remembered by ordinary Christian folk but for the providential accident that it serves us for a type of our Blessed Lady’s Child-bearing; she, like Gedeon’s fleece, was the one spot in our benighted and parched world where the dew of Divine Grace could find a lodgement, when in the fulness of time we were set free from the tyranny of our sins.

I say, a significant story, because it seems to me that it throws into relief a very important consideration which we are apt to overlook when we discuss the subject of miracles.

What consideration?

Why, this – that those special exercises of Divine power which we call miracles are not in themselves greater, are not in themselves more sensational, are not in themselves more deserving of our gratitude than His in nature. It was a wonderful sight, doubtless, when, after a sleepless night spent between hope and self-distrust, Gedeon went out at dawn to find the fleece wringing wet, glistening like silver in the grey light of mourning. And yet, when he went out the next day, was there not a still more wonderful vision awaiting him? A whole world silvered with dew, diamonds shining from every blade of grass and every fallen leaf, the very gossamer in the fields a patch-work of filigree? You have seen as much yourself, maybe, on some early summer morning in the country. Oh no, there was nothing wonderful about it, of course; you were quite right; it was just dew . . . Nothing wonderful, because we’re so accustomed to it, because we take it so for granted. When you saw that sight long ago, with the clear eyes of childhood, or with the transfiguring vision of first love, perhaps you caught the marvel of it; and since then, what exactly has happened? Is it that the dew-drenched world is less wonderful? Or that you have lost your faculty of wonder? It is important to realize that the same power which covered a single fleece with dew one night covered a whole landscape with dew the next night.

And which was the marvel?

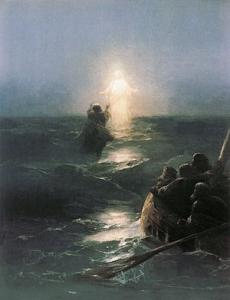

Which showed the greater exercise of power, which signalized God’s bounty in greater profusion? The first night, or the second? Because in the second instance we can account for the phenomenon, whereas in the first instance we cannot account for the phenomenon, we call the first instance a miracle. But if we had not lost the child’s faculty of wonder, we should see the same hand at work on the second night as on the first, only with more widespread effect, only with richer largesse. The same hand, the same power, only exercised in a different way. The same power which sent the stars rolling on their courses gives sudden health to some poor cripple at Lourdes, and we say, “Impossible!” The feeding of the Five Thousand, that taxes our powers of belief to the utmost. And yet, as Saint Augustine pointed out long ago, what is the feeding of the five thousand compared with that patient process by which vast plains of wheat shoot up and bud and mature, under God’s hand, to make the slices of bread which you forgot to say grace over yesterday? The same hand, the same power.

A miracle, though it ought to mean any event, natural or super-natural, which claims our wonder, is the term technically applied to a particular class of the wonderful works of God. God ordinarily brings events to pass in the natural world by means of secondary causes. When He suspends for a moment the action of those secondary causes, we call it a miracle. There are those who deny that any event of this kind has ever happened. And their arguments can be conveniently classed under three heads: Can God do miracles? Would God do miracles? And does God do miracles? I am not going to consider at present the question whether, as a matter of fact, miracles have ever happened. I want first to establish two points; that God can do miracles, if He will; and that there are circumstances in which we should expect God to do miracles, if He can.

Can God do Miracles?

From its very terms, such a question cannot be discussed with those who deny the existence of a deity. But there have been, and are people who are bound to return a negative to that question, because their philosophy has a conception of Almighty God’s nature which is altogether different from ours. A century or two ago, it was the Deists who felt bound to deny miracles. To-day, it is the Pantheists who feel bound to deny miracles. Deism was a passing fashion of yesterday, as Pantheism is a passing fashion of today. The one is the precise opposite of the other, but what of that? It is the world’s way to shift between extremes. The Church looks on with patience; she has seen so many of these changing moods, and she has outlived them all.

The Deists thought of creation as a machine which God had wound up, once for all, and left it to run its course by the inexorable law of its own mechanism. He was, indeed, the First Cause and the Prime Mover, but He did not uphold and govern His creation – He had left it to itself, as a man sets a ball rolling or a top spinning and goes his way. Naturally, such philosophers had to disbelieve in miracle. For a single variation from the unswerving laws by which the natural creation was governed would mean a spoke in the wheel, an interference which must needs set the whole machinery out of gear. The Pantheists of today think of Almighty God, rather, as if He were caught up in the wheels of His own machine. He is essential to our existence, says the Pantheist, but then, we in our turn are essential to His. He is to the world what man’s soul is to man’s body, a spiritual principle which pervades and inspires this mass of material creation. And of course, a God so conceived cannot stand outside His own Creation, cannot exempt Himself, therefore, from its natural laws, which are laws for Him no less than for us; once more, then, miracles must be declared impossible.

We have not time to consider here how grossly inadequate are both those conceptions of God. I will only say of such a God as that, that I would not cross the street to worship him. Those who would shelter themselves under the Christian Name are committed to a very different understanding of the Divine Nature.

In the beginning was God;

before suns or stars set out upon their course, He existed, eternally independent, eternally Self-sufficing; no room for Pantheism here. And yet, are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? And not one of them shall fall on the ground without your Father – the Deist, no less than the Pantheist, is silenced by the Christian revelation. For us, the Power which made the worlds out of nothing is the Power which still upholds, from day to day, from moment to moment, this vast fabric of Creation; it can experience no effect of which He is not the Cause, it can be stirred by no motion of which He is not the originator. Not one of them shall fall to the ground without your Father – when a sparrow flies against a telegraph wire and falls dead, it is He who supplies the force of its flight, and the resistance with which it meets; His Hand communicates the impact of the shock to the little fluttering heart, and draws the lifeless creature down into the bosom of its parent earth. That is the God we Christians worship.

But, you say, that is nonsense, that is to throw out a silly challenge to the whole world of science. If dew falls on the ground, you say, that is because the moisture with which the air is laden has condensed with the chill of night; that is the cause which produces the effect. The secondary cause, yes; the scientific cause, yes; but none of these secondary causes could operate for a moment without the concurrence of Almighty God. It is the law of gravitation which brings the sparrow to the ground; true enough, yet the law of gravitation itself – what is it but the direct expression of His will? Ordinarily, in all the million details of our daily experience, He works thus, expressing His will through the laws which Science tabulates for us, laws which operate uniformly, no effect without its cause, back to the first amoeba in which life was found, back to the first nebula from which matter took birth – and yet, all the time it is His power, directly exercised, which lends these causes their efficacy. You are puzzled by miracles? I tell you, if you could only recognize the necessity of God’s action in the world, the fall of a sparrow to the ground would be ten thousand times more staggering to your poor, finite imagination. It is a thing to make you dream at night, and wake gasping with the wonder of it. And a miracle –

A miracle is a very simple thing by comparison.

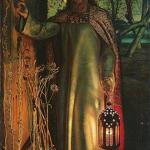

It happens when, once and again in these long aeons of the world’s existence, God expresses His will more directly, by suspending for a moment, at one tiny pin-point of space, the operation of those laws which could have no force and no validity but from Him. Just in the millionth instance God does, without the aid of secondary causes, what He is continually doing by means of secondary causes. Just in the millionth instance He multiplies bread instead of multiplying the wheat. Just in the millionth instance He will have the dew form not everywhere but just here. Is that so much of a privilege to claim for the Omnipotent? Is that impossible with God, with such a God?

I may be pardoned for giving a very simple and a very vulgar illustration; I use it reluctantly because I want to bring this point home. There are such people as newspaper proprietors; and some of these proprietors are in the habit of dictating, from day to day, the policy of the papers they own. All the leading articles – we will not speak of the news service – are written by men who are paid to express, in every line they write, the will of a newspaper proprietor. Now, suppose that once in ten years, on some exceptionally important occasion, a newspaper proprietor should write his own leading article. What is he doing? He is doing what he does every day; the only difference is that just this once he is doing directly what he has been doing daily for ten years through the instrumentality of others. That will give some idea of what I mean when I say that the God who operates continually through secondary causes has the right, if He will, to dispense with secondary causes.