I like to keep up with newer books that have been published but have not done so in quite awhile.

It’s nice to know who is writing what today.

So here are some newer non-fiction books that have come out in the last few years that look interesting.

Book lists give you a chance to familiarize yourself with things out there you would read if you could.

It gives you a knowledge of books and who has written what when.

You can then talk about those books you haven’t read as if you have read them

The non-fiction books are presented of where you would find them in a library using the Dewey Decimal System.

I cover books from 000 Knowledge to 500 Science.

I list a particular title and a small sample of what the book has to offer the reader. It is basically a glorified book list of quotes of newer books.

“He wished he was with his mom in her library, where everything was safe and numbered and organized by the Dewey decimal system. Ben wished the world was organized by the Dewey decimal system. That way you’d be able to find whatever you were looking for, like the meaning of your dream, or your dad.”

― Brian Selznick, Wonderstruck

Please Note that I might not agree with everything a particular author has written in other books or maybe even in the book I’m listing. For example, I might agree with the science in a science book and disagree with the philosophical and theological conclusion there is no God.

Nonfiction general works

“The non-fiction bestseller lists frequently prove that we all want to know more about everything, even if we didn’t know that we wanted to know – we’re just waiting for the right person to come along and tell us about it.”

― Nick Hornby

00 Computer science, information & general works

The Secret History of Bigfoot:

Field Notes on a North American Monster (2024)

by John O’Connor

MDS 001 Knowledge

In truth, one rarely thinks about why they’re looking into something until long after they’ve begun. Bigfoot was probably always there, in the back of my mind. Perhaps I thought it would fade. Instead it gained momentum. After abandoning my blockbuster film treatment, “Wrath of the Squatch,” I began imbibing the Bigfoot literature, the podcasts and chat room banter, Instagram posts and Facebook rants. I watched the unwatchable films, spoke to believers and non, diehards and weekenders, clearheaded skeptics and fervid charlatans, plumbing the thin margins between credible and contrivance, between reasoned inquiry and unhinged pursuit of a creature whose exact location no one could specify but whose existence was taken as a matter of faith.

Bigfoots, you may be surprised to learn, aren’t all that rare. In fact, by most accounts, they’re quite common, or no less widely dispersed than, say, bald eagles or Starbucks. Each year, hundreds of Bigfoots are sighted across the United States and Canada, from Alberta to Alabama, Saskatchewan to South Carolina, and thousands more “encountered” via footprints, calls, and “wood knocks,” a form of communication that entails pounding on trees. Visitors to Ohio’s scanty twenty-six-square-mile Salt Fork State Park, which is flanked by some of the Midwest’s busiest highways, have recorded dozens of sightings.

Nexus:

A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI (2024)

by Yuval Noah Harari

MDS 001.09 Knowledge

If we Sapiens are so wise, why are we so self-destructive? At a deeper level, although we have accumulated so much information about everything from DNA molecules to distant galaxies, it doesn’t seem that all this information has given us answers to the big questions of life: Who are we? What should we aspire to? What is a good life, and how should we live it? Despite the stupendous amounts of information at our disposal, we are as susceptible as our ancient ancestors to fantasy and delusion. Nazism and Stalinism are but two recent examples of the mass insanity that occasionally engulfs even modern societies. Nobody disputes that humans today have a lot more information and power than in the Stone Age, but it is far from certain that we understand ourselves and our role in the universe much better. Why are we so good at accumulating more information and power, but far less successful at acquiring wisdom?

Face with Tears of Joy:

A Natural History of Emoji

by Keith Houston

MDS 004 Data processing and computer science

I am the last person who should be writing a history of emoji. I was born at the tail end of Generation X, which means I am now sufficiently old that it is impossible for me to use emoji in a way that is not either embarrassing or mildly creepy. And despite having written computer software for a living for the better part of two decades, I am also a borderline Luddite. I did not buy a smartphone until the mid-2010s, long after emoji had first appeared, and it was years before I dared use emoji in anger. (Or in joy. Or in whatever emotion a picture of a sassy lady painting her fingernails conveys.)

But emoji do not care who writes about them. They have become so ubiquitous in our writing, so quotidian, that we should be talking about them in the same breath as grammar or punctuation. You use them. Your boss uses them. Your mom uses them. Cher uses them, a lot. Emoji no longer respect the boundaries that once contained them, which has simultaneously robbed them of their mystique* and opened them up to criticism. We now have a quarter century of emoji history to explore—more than that, even, since emoji’s roots stretch much further into the past—and a richness of emoji usage that rivals any language.

The Thinking Machine:

Jensen Huang, Nvidia, and the World’s Most Coveted Microchip

by Stephen Witt

MDS 006 Special computer methods (e.g. AI, multimedia, VR)

This is the story of how a niche vendor of video game hardware became the most valuable company in the world. It is the story of a stubborn entrepreneur who pushed his radical vision for computing for thirty years, in the process becoming one of the wealthiest men alive. It is the story of a revolution in silicon and the small group of renegade engineers who defied Wall Street to make it happen. And it is the story of the birth of an awesome and terrifying new category of artificial intelligence, whose long-term implications for the human species cannot be known.

Cabinet of Curiosities:

A Historical Tour of the Unbelievable, the Unsettling, and the Bizarre (2024)

by Aaron Mahnke

MDS 030 General encyclopedic works

My team and I have spent the past five years gathering the most amazing, entertaining, and enlightening stories from history and placing them into a modern, digital cabinet of curiosities. Yes, every story is a little object sitting on a shelf by itself, and that’s all well and good. But it’s time for a bit of organization.

So please, enjoy your tour through a new kind of cabinet of curiosities. Walk the width and length of our gallery, and take in the wonders that are on display. I’ve worked hard to curate this ever-evolving exhibit of the most fascinating tales from history, and I’m certain that you’ll enjoy visiting these incredible places, unusual characters, and amazing events. That is, of course, if you’re more than a little … curious.

SECOND LIFE: It’s one of many tales of the founding of America. Settlers from England were exploring more and more of the New World, and as they did, they set up new communities far from the comfort of home. We know these stories as well as the backs of our hands, if not in detail then at least in theme. Most of the original states have a story that echoes these themes, but there’s one tale in particular that I want to tell you.

100 Philosophy and Psychology

In My Time of Dying:

How I Came Face to Face with the Idea of an Afterlife (2024)

by Sebastian Junger

MDS 128.5 Humankind

Everyone has a relationship with death whether they want one or not; refusing to think about death is its own kind of relationship. When we hear about another person’s death, we are hearing a version of our own death as well, and the pity we feel is rooted in the hope that that kind of thing—the car accident, the drowning, the cancer—could never happen to us. It’s an enormously helpful illusion. Some people take the illusion even further by deliberately taking risks, as if beating the odds over and over gives them a kind of agency. It doesn’t, but it’s an odd quirk of neurology that when we are fighting the hardest to stay alive, we are hardly thinking about death at all. We’re too busy.

Are You Mad at Me?:

How to Stop Focusing on What Others Think and Start Living for You (2025)

by Meg Josephson

MDS 155.232 Differential and developmental psychology

Today, it may seem odd that we worry so much about how others perceive us given that we’re in constant communication with one another. But it’s precisely because of this endless receiving and giving of external validation and reassurance—texting, hearting others’ texts, liking their posts, FaceTiming, DMing videos—that we are sent into tailspins of insecurity. When our bodies are so used to that intense amount of communication and then it’s reduced in any way, this can easily send the part of ourselves that is focused on survival into a spiral. There are so many ways to tell someone you’re thinking of them, and because of that, there are also so many opportunities to feel forgotten.

The Let Them Theory (2024)

by Mel Robbins

MDS 158 Self-Help & Relationships

Over the years I have wondered, Why do I need to constantly force myself to move forward? Why am I so afraid of failing? Why am I so nervous about taking a risk? Why do I have a hard time asking for what I need? What exactly is in my way?

Have you ever truly stopped and considered these questions for yourself: Why do you hesitate? What is it that is causing you to procrastinate? Or feel so tired? Or overthink every decision? What’s underneath all that doubt? What is stopping you from doing what you need to do or living your life the way you want to live it? What are you afraid of?

I was shocked when I discovered the answer for myself: It was other people. Or rather, how I was letting other people impact me. I was spending too much time and energy managing or worrying about other people. What they do, what they say, what they think, how they feel, and what they expect from me. The reality is, no matter how hard you try or what you do, you cannot control other people. And yet, you live your life as if you can.

You live as though, if you say the right things, people will like you. If you keep taking on more work, your boss will respect you. If you act in the right way, and cater to what your mom wants, and also keep your friends happy, somehow you’ll find peace. You won’t.

How to Be Abe Lincoln:

Seven Steps to Leading a Legendary Life (2023)

by Jonathan Shapiro

MDS 158.1 Self-Help & Relationships

Plenty of books give us the heroic Lincoln. What we need is a book that gives us the practical Lincoln, one that shows us how to survive a fractious age. This is that book. It is written for those who don’t just admire Lincoln but want to emulate him. It identifies the seven steps that made Abe Lincoln legendary and teaches you how to follow them.

This is not a new concept. Studying the life of a legend to learn how to live better is an old and admired practice. It is also effective. Lincoln is proof. By taking the seven steps that are outlined in this book, Abe Lincoln really and truly became . . . Abe Lincoln. To be Abe Lincoln, you must learn to:

- Laugh.

- Improve.

- Navigate.

- Collaborate.

- Object.

- Love.

- Now.

200 Religion

100 Places to See After You Die:

A Travel Guide to the Afterlife (2023 )

by Ken Jennings

MDS 202 .3 Doctrines

When you look at afterlife journeys from stories told over the millennia, from ancient Sumer all the way up to The Good Place, the same routes and themes recur over and over. Ghosts are in at least their fifth century of moping around their old houses, moving objects by focusing very hard on them, and not even always knowing that they’re dead. “Psychopomps,” immortal guides, still appear after death to lead the soul away from mortal life. Heavens, whether Miltonian, Hindu, or Capra-esque, are still heavy on music and clouds and wings. Hell hasn’t changed much between ancient China or Mesoamerica and South Park: still the same turnabout-is-fair-play “ironic” punishments, the same jaw-droppingly long torture sessions, even the same gross bodily fluids. Dim underworlds still lie across rivers. (This trope probably arose from simple geology. Early humans knew that wells were deeper than graves, so buried souls would have to cross a layer of water as they headed downward.)

Believe:

Why Everyone Should Be Religious

by Ross Douthat

MDS 231.042 God

The heavens declare the glory of God, the Bible says, and when the biblical God wants to answer a suffering mortal’s questions in the book of Job, He goes straight to this initial human intuition. The intuition that the world seems like a workshop and a cathedral and a theater and a machinist’s shop and more. That nothing so vast and complex and beautiful could exist by simple accident. That either some Mind or Power must have made or organized all this matter for a reason, or else the Mind or Power is somehow inherent to the system, and the cosmos itself divine.

From this perspective, you may still doubt the straightforward goodness of the system- because the world is so often painful, dangerous, tragic, a vale of tears- and question the perfect benevolence of whatever Power governs it. But that Power clearly matters to your existence in such a fundamental way that it would be strange to to wonder about its purposes or where you fit into them, self-defeating to care about how your own life aligns with the story in which you have been placed. And when the story’s Author speaks to you, as God speaks to Job and his friends, it’s clearly a good idea to show a little respect.

Seeing the Supernatural:

Investigating Angels, Demons, Mystical Dreams, Near-Death Encounters,

and Other Mysteries of the Unseen World

by Lee Strobel

MDS 235 Spiritual beings

When William Peter Blatty set out to write the classic horror film The Exorcist, he had an agenda—and it wasn’t simply to scare audiences to their core (though he did manage to do exactly that).

Reeling from the death of his beloved mother, the screenwriter best known for authoring a Pink Panther comedy decided there was a critically important message that needed to be shared with an increasingly skeptical populace: “The spiritual world is real.” “I wanted to write about good and evil and the unseen world all around us,” he told journalist Terry Mattingly. “I wanted to make a statement that the grave is not the end, that there is more to life than death.”

To Blatty, who earned an Academy Award for his script, the logic was inexorable: “If demons are real, why not angels? If angels are real, why not souls? And if souls are real, what about your own soul?”

Want You to Be Happy: Finding Peace and Abundance in Everyday Life (2025)

by Pope Francis

MDS 248 Christian experience, practice, life

Being Christians means having a new perspective, and looking at things with hope. We believe and know that death and hate are not the final words on the parabola of human existence.

Some people believe that we only know happiness when we are young, that it is bound up in the past, that life is actually slow deterioration. Others think that any kind of joy we experience is fleeting and momentary, that human life is meaningless.

But we Christians do not think that. No, we believe that resting on the horizon of life is a sun that shines forever. We believe that our most beautiful days are yet to come. We are people of the spring, as opposed to the autumn. Let us look to the buds of a new world rather than yellowed leaves on its branches.

A Christian knows that the kingdom of God, the dominion of Love, grows like a vast field of wheat, and that it may well have weeds in its midst. There are always problems: people gossip, there are wars, there is illness… But even so, the wheat ripens, and in the end evil will be eliminated.

We know that the future does not belong to us. We know that Jesus Christ is life’s greatest grace. We know that God’s warm embrace not only awaits us at life’s end but also accompanies us on our journey every day.

Let us not cultivate nostalgia, regret and sorrow. God wants us to be the heirs of a promise; he wants us to be tireless growers of dreams.

Check Out 25 New Catholic Books in 2025

Becoming Free Indeed:

My Story of Disentangling Faith from Fear (2023)

Jinger Duggar Vuolo,

MDS 289 Other denominations and sects

Here’s one of the many quirky facts about being a Duggar: my husband, Jeremy, and I didn’t watch our first movie together until we were husband and wife. On our honeymoon in 2016, we watched The Truman Show. I had never seen it before. (That’s something I can say about a lot of movies!) After we finished the movie, I turned to Jeremy and said, “That movie is my life.” Well, except for the spouse-picking part. I’ve been on television since I was ten years old.

Life on TV has its perks as well as its challenges. For me, one of those challenges has been dealing with other people’s expectations. When strangers expect me to make certain decisions—even rooting for me to make them as if I’m a character on a sitcom—they seem to forget that I’m a real person with my own feelings and emotions. Add my family’s values to the equation and you get even more criticism, opinions, and debates about how I should live. Every decision is put under a microscope, dissected, and either criticized or praised.

Dear Alyne:

My Years as a Married Virgin

by Alyne Tamir

MDS 289 Other denominations and sects

This was my wedding night. My heart dropped. I was afraid. I didn’t have the tools to communicate how I really felt, so instead of saying, “Hey, I really don’t want to disappoint you, but I feel really stressed and unprepared and overwhelmed, and I’m having a lot of uncomfortable feelings I can’t even explain,” I said: “We should play Speed Scrabble IN the shower! That would be so fun, right!?” It was our first time seeing each other naked. But instead of looking at each other, or exploring each other, we were looking at a Scrabble board. And it was all my fault.

For all my life, up until that moment, virginity had been the foundation upon which my every decision was built. At my college, Brigham Young University, a Mormon aka Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints school, sex was a punishable act—you would be literally expelled, your hope for a degree lost, your marriage prospects and reputation destroyed—no matter how far along you were in your degree. No pressure! Just your entire future at stake. Shorts and skirts above the knee were forbidden to help avoid temptation and promote modesty. Men couldn’t grow beards without a “beard card” for special permission. And as for shoulders? Those sexy surfaces were to be completely covered at all times. No tank tops allowed.

I’d somehow internalized that any sexuality, even in marriage, was something to be suppressed.

290 Other religions

Flight of the Bön Monks:

War, Persecution, and the Salvation of Tibet’s Oldest Religion (2024)

by Harvey Rice, Jackie Cole

MDS 299.54 Religions not provided for elsewhere

The monks carried the few sacred texts and artifacts they had been ale to rescue from their monasteries before they were looted y Chinese troops. Tenzin carried the most sacred object: a six-hundred-year-old reliquary containing the ashes of the founder o the Bon’s premier monastery. The artifacts were mere slivers of a culture under assault by the Chinese. Soldiers were torturing and killing monks, razing temples and destroying texts, statues, and paintings. Tenzin’s world was being ripped apart. Escape was the only way to ensure the monk’s survival and of Bon itself.

Their only escape route was across the daunting Himalayas that lay south of the vast plateau. In Sanskrit, Himalaya means “the abode of snow.” The Himalayas would be the final abode or untold numbers of Tibetans as they died from hunger, cold, avalanches, and steep plunges from rocky heights during their long trek to freedom.

Moving as fast as possible, members of Tenzin’s party continually cast wary eyes behind them. Tenzin ran for his life.

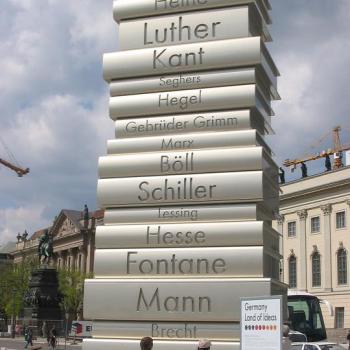

300 Social Sciences

Revenge of the Tipping Point:

Overstories, Superspreaders, and the Rise of Social Engineering

by Malcolm Gladwell

MDS 302 Social interaction

Twenty-five years ago, I published my first book. It was entitled The Tipping Point: How Little Things Make a Big Difference. Back then I had a little apartment in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, and I would sit at my desk, with a glimpse of the Hudson River off in the distance, and write in the mornings before I headed to work. Because I had never written a book, I had no clear idea how to do it. I wrote with that mix of self-doubt and euphoria common to every first-time author. “The Tipping Point is the biography of an idea,” I began, “and the idea is very simple.”

Twenty-five years is a long time. Think about how different you are today than you were a quarter-century ago. Our opinions change. Our tastes change. We care more about some things and less about others. Over the years, I would sometimes look back on what I had written in The Tipping Point and wonder how I ever came to write the things I did. An entire chapter on the children’s television shows Sesame Street and Blue’s Clues? Where did that come from? I didn’t even have children back then. I moved on to write Blink, Outliers, David and Goliath, Talking to Strangers, and The Bomber Mafia. I started the podcast Revisionist History. I settled down with the woman I love. I had two children and buried my father and took up running again and cut my hair. I sold the Chelsea apartment. I moved out of the city. A friend and I started an audio company called Pushkin Industries. I got a cat and named him Biggie Smalls.

Knowing What We Know:

The Transmission of Knowledge: From Ancient Wisdom to Modern Magic (2023)

by Simon Winchester

MDS 306.42 Culture and institutions

The arc of every human life is measured out by the ceaseless accumulation of knowledge. Requiring only awareness and yet always welcoming curiosity, the transmission of knowledge into the sentient mind is an uninterruptible process of ebbings and flowings. There are times—in infancy, or when at school in youth—during which the rate at which knowledge is gathered becomes intense and urgent, a welling tsunami of information ever ready for the mind to process. At other times, maybe later in life, the inbound knowledge drifts in more slowly, set to adhere and thicken like moss, or a patina.

What You Should Know About Politics

. But Don’t, Fifth Edition: A Nonpartisan Guide to the Issues That Matter (2024)

by Jessamyn Conrad

MDS 320 Political science (Politics and government)

Personally, I’m not much of an ideologue. Because North Dakota does not require me to register to vote, I have no party affiliation. If I had one, I’d be a disappointed Democrat with a strong libertarian streak. In another era, I probably would have been a Rockefeller Republican. I loathe the entrenched political machines of both parties, which I think are dangerous and far too often misleading, manipulative, and fundamentally dishonest. So in that sense, you might say I’m a populist. My most politically informed friend calls me a pragmatist, and that’s about right. I get my undies in a bunch when people lie. I want things to work well. I think we probably should be nice to other people as much as possible, but I believe there’s such a thing as evil in the world, too. Mostly, I’m glad I don’t have to make these decisions. I don’t know what I would do about gun control or the death penalty or trade agreements if it were up to me. Like most Americans, I’m conflicted on many issues.

The Year of Living Constitutionally:

One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Constitution’s Original Meaning (2024)

by A.J. Jacobs,

MDS 342.73 Constitutional and administrative law

My goal is to understand the Constitution by expressing my rights as they were interpreted back in the era of Washington and Madison (or, in the case of the later amendments, how those amendments were interpreted when they were ratified). I want, as much as possible, to get inside the minds of the Founding Fathers. And by doing so, I want to figure out how we should live today. What do we need to update? What should we ignore? Is there wisdom from the eighteenth century that is worth reviving? And how should we view this most influential and perplexing of American texts?

Just how much our lives are affected by this 4,543-word document inscribed on calfskin during that long-ago Philadelphia summer.

And it’s not just the issues we’re divided on—it’s the Constitution itself. Is the Constitution a document of liberation, as I was taught in high school? Or is it, as some critics argue, a document of oppression? Should we venerate this brilliant road map that has arguably guided American prosperity and expanded freedom for 230-plus years? Or should we be skeptical of this set of rules written by wealthy racists who thought tobacco-smoke enemas were cutting-edge medicine?

Framed:

Astonishing True Stories of Wrongful Convictions (2024)

by John Grisham

MDS 345 Criminal law

“Each of these stories is told with astonishing power.”—David Grann, author of The Wager

In 2006, I published The Innocent Man, a true story about the wrongful conviction and near execution of Ron Williamson. Before then, I had never considered nonfiction—I was having too much fun with the novels—but Ron’s story captivated me. From a pure storytelling point of view, it was irresistible. Filled with tragedy, suffering, corruption, loss, near death, a measure of redemption, and an ending that could not be considered happy but could have been much worse, the story was just waiting for an author. I soon learned that every wrongful conviction deserves its own book. Since then I’ve met many exonerees, along with their families,

This Ordinary Stardust:

A Scientist’s Path from Grief to Wonder (2024)

by Alan Townsend

MDS 362 Social problems of and services to groups of people

Decades ago, I became entranced by the stardust that resides in all of us. I sat in a California lecture hall and listened to my biology professor talk about the ways we pass that stardust not only between one another but to everything else on earth. About how those exchanges can happen in the tiniest of spaces or across the world, sometimes every second, sometimes not for millions of years. And about how our own species was rewriting the rules of the game.

It hooked me. And while the whole “we are made of stardust” thing is also a total cliché, when the lecture ended, I thought: that stupid hippie bumper sticker was a true and literal statement of who we are, our nature as well as our limits. When viewed in our most elemental form, people are trillions of outer-space atoms, moving around temporarily as one, sensing and seeing and falling in love. Then those atoms scatter, joining one new team for a bit, then another. Far from depressing, I found this notion profoundly comforting. Sure, “I” the atomic collective wouldn’t be around all that long in the grand scheme of things—but my atoms would, forever remixing and reencountering one another. I thought: No matter what happens, we’re still here. And we always will be.

The Barn:

The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi

by Wright Thompson

MDS 364 Criminology

“An incredible history of a crime that changed America.” —John Grisham

author of Framed:Astonishing True Stories of Wrongful Convictions

I first heard about the barn four years ago. The barn where Till was murdered, Patrick said, was just some guy’s barn, full of decorative Christmas angels and duck-hunting gear, sitting there in Sunflower County without a marker or any sort of memorial, hiding in plain sight, haunting the land. The current owner was a dentist. He grew up around the barn. When he bought it, he didn’t know its history. Till’s murder, a brutal window into the truth of a place and its people, had been pushed almost completely from the local collective memory, not unlike the floodwaters kept at bay by carefully engineered reservoirs and levee walls.

400 Language

Australia in 100 Words

by Amanda Laugesen

MDS 408 Groups of people

If you were asked to nominate 100 words that tell the story of Australia, how would you go about it? You’d probably pick out some of the words that many see as quintessentially Australian: fair go, Aussie, Anzac, larrikin, or bush might be some of them. You might choose a few that reflected our history, such as digger or bushranger. You might choose a bird or an animal, and maybe a plant: emu or wombat or gum tree, perhaps. A few colourful phrases would also have to be there: perhaps you would select flash as a rat with a gold tooth or flat out like a lizard drinking. But settling on 100 words and expressions to tell the story of a nation is no easy task, as I can attest after having done it myself for this book.

The Origin of Language: How We Learned to Speak and Why (2025)

by Madeleine Beekman

417.7 Dialectology and historical linguistics

Growing a large brain is expensive—so expensive that mothers cannot allow their babies to stay in the womb until that brain is more fully grown. The consequence of this is that our babies are born early; their heads are too large, their brains are too expensive, and their mothers’ birth canals are too narrow for them to be born any later than they are. Thus, the babies are seriously “underbaked.” So underbaked, in fact, it takes them almost two decades to catch up, a time during which they have to rely on others. As the brain expanded and the head changed shape, the throat did too. The larynx descended, pulling the tongue with it. And that change led to two uniquely human characteristics. One is a high risk of choking on our food and drink, and the other is the ability to mold sounds like no other creature. Sounds we crafted into the language needed to organize our childcare.

Enough Is Enuf:

Our Failed Attempts to Make English Eezier to Spell

by Gabe Henry

MDS 428 Standard English usage (Prescriptive linguistics)

Why does the G in wage sound different from the G in wag? Why does C begin both crease and cease? And why is it funny when a phonologist falls, but not polight to laf about it? Anyone who has the misfortune to write in English will, every now and then, struggle with its spelling. In our woeful orthography, choir and liar rhyme, daughter and laughter don’t, and God help you if you encounter a pterodactyl out in the wild. There’s an old British joke, first told around 1855, about a nervous schoolboy who is called upon to spell the word fish. He understands just enough about English spelling to be utterly confused by it. He knows that GH makes the sound of an F in tough, O sounds like an I in women, and TI is pronounced SH in station. And so he recites this combination:

G-H-O-T-I

There’s a reason spelling bees are only common in English-speaking countries: English spelling is absurd.

500 Science

The Beast in the Clouds:

The Roosevelt Brothers’ Deadly Quest to Find the Mythical Giant Panda

by Nathalia Holt

MDS–508 Natural history

The 1920s were a decade of discovery, as groups of scientists, adventurers, and hunters ventured forth into the wilderness to fill museum collections. They were successful: every large mammal on earth had been attained, and their bodies mounted in exhibits, except for one.

The Roosevelts desired this one animal so acutely that they could barely speak about it with each other, much less anyone else. “We did not let even our close friends know,” wrote Ted of their shared purpose. Some dreams sound too wild when spoken aloud. The animal the Roosevelt brothers coveted looked like no other species in the world. It was a black-and-white bear so rare that many people did not believe it was real. This legendary creature was called the giant panda. Rumors swirled about the mysterious animal. No one, not even naturalists who had worked in China all their lives, could say precisely where the creature lived, what it ate, or how it behaved.

Brown, black, and polar bears had never been in doubt among humans. Even polar bears, although living in the remote reaches of the Arctic, were well known, and had been kept in zoos for thousands of years. In Egypt, King Ptolemy II had a polar bear in his zoo in Alexandria as early as 285 BC. In 1252, a polar bear was part of the Tower of London’s extensive menagerie of beasts.

Yet the same could not be said of the panda bear.

Pillars of Creation:

How the James Webb Telescope Unlocked the Secrets of the Cosmos

by Richard Panek

MDS–522.2 Techniques, procedures, apparatus, equipment, materials

How much farther in space? How much farther in time?

Even before the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope in 1990, its successor-the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) – was in the works. At that point in the history of astronomy, nobody knew precisely what horizons the Hubble telescope would identify. But astronomers were confident that it would identify some new horizon-a horizon that would excite the curiosity of the next generation of astronomers, the horizon for which they would need a more powerful tool in order to cross.

Dinosaurs at the Dinner Party:

How an Eccentric Group of Victorians Discovered Prehistoric Creatures

and Accidentally Upended the World

by Edward Dolnick

MDS–567.9 Fossil cold-blooded vertebrates

The tracks on that New England farm, it would turn out, had been made two hundred million years before, by a dinosaur. In 1802 no one had ever heard of dinosaurs. These were, as far as anyone knew, the first dinosaur tracks ever found.

That find was as strange and unexpected as any discovery in human history. A series of similar discoveries followed, in rapid succession and across the globe. The finds were giant bones and enormous footprints in stone and, soon, immense skeletons. No living creatures looked like this. Whose bones were these?

Today every child knows the answer. But in the early decades of the 1800s, no one had any inkling that there had ever been such creatures as dinosaurs. The word dinosaur would not be coined until 1842.

That seems awfully late in the day, especially considering how much we now take dinosaurs for granted. Today every natural history museum in the world boasts an enormous dinosaur skeleton that scrapes the ceiling and pokes its head out into the hall. Every kindergarten class has a plastic dinosaur or two near the shelves with the crayons and the blunt-nosed scissors. Every toddler has pajamas with cartoon dinosaurs or a bin stuffed with toy dinosaurs.

But a time traveler from 1800 would look at those toys and relics in bewilderment. Shakespeare, who imagined everything, never imagined a world ruled by house-sized beasts and where human beings had never set foot. The world’s most farseeing thinkers had never seen that far. No such possibility had ever crossed the mind of Leonardo da Vinci or Galileo or Isaac Newton or Benjamin Franklin.

Is a River Alive?

by (2025) Robert Macfarlane

MDS–577.64 Ecology

I wish to say plainly and early that this book was written with the rivers who run through its pages, among them the Río Los Cedros, the Adyar, the Cooum and the Kosasthalaiyar, the Mutehekau Shipu, the mighty St Lawrence, and the clear-watered stream who flows unnamed from the spring that rises at Nine Wells Wood, a mile from my house, and who keeps time across the pages that follow. They are my co-authors.

One morning when we were walking to school together, my son Will asked me the title of the book I was writing. ‘Is a River Alive?,’ I told him. ‘Well, duh, that’s going to be a short book then, Dad,’ he replied, ‘because the answer is yes!’

Most of us, I think, once felt rivers to be alive. Young children are natural explorers of the vivid in its old sense: from the Latin vividus, meaning ‘spirited, lively, full of life’. Young children instinctively inhabit and respond to a teeming world of talkative trees, singing rivers and thoughtful mountains. This is why in so much children’s literature – from fairy tales to folk tales, across centuries and languages – a speaking, listening, convivial landscape is a given.

Secrets of the Octopus (2024)

by Sy Montgomery

MDS– 594 .56 Mollusca and Molluscoidea

I’d never met anyone like Athena before. Athena was a giant Pacific octopus, an Enteroctopus dofleini. We met at the New England Aquarium in Boston. While all of the octopuses I came to know were playful and intelligent, each displayed a distinct personality. Octavia, who replaced Athena after she died, was standoffish at first but became a very gentle, loving, and stalwart friend. I wrote of my friendships in a book published in 2015. Its title, The Soul of an Octopus, gave some readers pause. How can an octopus have a soul? (Many scientists and philosophers don’t believe in souls; some believe humans don’t even possess consciousness—that it’s just a made-up concept to help us handle the pointlessness of existence.) Octopuses are mollusks, relatives of brainless clams. Surely, some said, suggesting an octopus might have a soul, or a personality, or thoughts or memories or emotions, was simply a product of a misguided human propensity to anthropomorphize animals, to wrongly attribute “human” feelings to non-human creatures, like a child pretends that a doll is really alive. These folks are mistaken.

In another article I will cover new non-fiction books from 600 Technology – 900 History and Geography.