In the last offering in this series [1] your humble servant promised to explore Pope Leo XIII’s objection to socialism on natural law grounds, and this I will now endeavor to do. For those of you following along, we are in the midst of Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum novarum [2], wherein he, among other things, explained why socialism was not an adequate remedy for the serious plight of the working class in his day.

The natural law rationale that he gave was based on human reason and the way that property is primitively acquired. By means of these he concluded that a human being “has by nature the right to possess property as his own,” (Ibid, §6) while the socialists were contending that justice could only be served if that right was abolished.

Human reason, the Pope said, gave us the power to understand and prepare for our needs over time. He put it this way:

“It is the mind, or reason, which is the predominant element in us who are human creatures; it is this which renders a human being human, and distinguishes him essentially from the brute. And on this very account – that man alone among the animal creation is endowed with reason – it must be within his right to possess things not merely for temporary and momentary use, as other living things do, but to have and to hold them in stable and permanent possession; he must have not only things that perish in the use, but those also which, though they have been reduced into use, continue for further use in after time.

“It is the mind, or reason, which is the predominant element in us who are human creatures; it is this which renders a human being human, and distinguishes him essentially from the brute. And on this very account – that man alone among the animal creation is endowed with reason – it must be within his right to possess things not merely for temporary and momentary use, as other living things do, but to have and to hold them in stable and permanent possession; he must have not only things that perish in the use, but those also which, though they have been reduced into use, continue for further use in after time.

“This becomes still more clearly evident if man’s nature be considered a little more deeply. For man, fathoming by his faculty of reason matters without number, linking the future with the present, and being master of his own acts, guides his ways under the eternal law and the power of God, whose providence governs all things. Wherefore, it is in his power to exercise his choice not only as to matters that regard his present welfare, but also about those which he deems may be for his advantage in time yet to come. Hence, man not only should possess the fruits of the earth, but also the very soil, inasmuch as from the produce of the earth he has to lay by provision for the future. Man’s needs do not die out, but forever recur; although satisfied today, they demand fresh supplies for tomorrow. Nature accordingly must have given to man a source that is stable and remaining always with him, from which he might look to draw continual supplies.” (Ibid, §§6-7)

Without private property we cannot secure provisions for the future, but instead are left to whatever nature can afford us at the moment of need. But God has given us the double gift that we are capable of both understanding our future needs and providing for them. And since God did not give us this ability only to frustrate us, it follows that we are to make use of it, and the use of it results in private productive property. And here we see why many socialists have found atheism to be a useful posture toward life.

The Holy Father also pointed out that the very means we acquire things from nature gives us a right to ownership of those very things. He said,

“Truly, that which is required for the preservation of life, and for life’s well-being, is produced in great abundance from the soil, but not until man has brought it into cultivation and expended upon it his solicitude and skill. Now, when man thus turns the activity of his mind and the strength of his body toward procuring the fruits of nature, by such act he makes his own that portion of nature’s field which he cultivates – that portion on which he leaves, as it were, the impress of his personality; and it cannot but be just that he should possess that portion as his very own, and have a right to hold it without any one being justified in violating that right.

“So strong and convincing are these arguments that it seems amazing that some should now be setting up anew certain obsolete opinions in opposition to what is here laid down. They assert that it is right for private persons to have the use of the soil and its various fruits, but that it is unjust for any one to possess outright either the land on which he has built or the estate which he has brought under cultivation. But those who deny these rights do not perceive that they are defrauding man of what his own labor has produced. For the soil which is tilled and cultivated with toil and skill utterly changes its condition; it was wild before, now it is fruitful; was barren, but now brings forth in abundance. That which has thus altered and improved the land becomes so truly part of itself as to be in great measure indistinguishable and inseparable from it. Is it just that the fruit of a man’s own sweat and labor should be possessed and enjoyed by any one else? As effects follow their cause, so is it just and right that the results of labor should belong to those who have bestowed their labor.” (Ibid, §§9-10)

“So strong and convincing are these arguments that it seems amazing that some should now be setting up anew certain obsolete opinions in opposition to what is here laid down. They assert that it is right for private persons to have the use of the soil and its various fruits, but that it is unjust for any one to possess outright either the land on which he has built or the estate which he has brought under cultivation. But those who deny these rights do not perceive that they are defrauding man of what his own labor has produced. For the soil which is tilled and cultivated with toil and skill utterly changes its condition; it was wild before, now it is fruitful; was barren, but now brings forth in abundance. That which has thus altered and improved the land becomes so truly part of itself as to be in great measure indistinguishable and inseparable from it. Is it just that the fruit of a man’s own sweat and labor should be possessed and enjoyed by any one else? As effects follow their cause, so is it just and right that the results of labor should belong to those who have bestowed their labor.” (Ibid, §§9-10)

In a world where most real estate that is owned has been acquired ultimately by conquest, this might be a little hard to swallow. In fact, we see now too often that those who labor do not acquire productive property at all. But a little analysis will reveal that it is really force that keeps the laborer from the fruits of his labor; whether it be the force of the conqueror, the force of the robber, or the force of the State through its property laws.

The socialists that Pope Leo XIII was confronting were able to understand how that force functioned better than most. Unfortunately, their remedy was to make that force complete, and deprive humans of the right to acquire productive property at all. As a believer in natural law, the Holy Father was compelled to reject that solution.

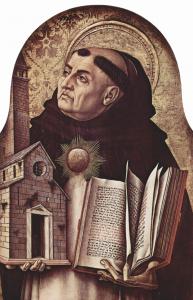

The icon of St. Joseph the Worker is by Daniel Nichols.

Listen to Christian Democracy on live internet radio on Tuesdays at 10:30 p.m. Eastern time at WCAT Radio here, or listen to the podcast here on the Christian Democracy Patheos blog.

Please go like Christian Democracy on Facebook here. Join the discussion on Catholic social teaching here.