I felt it rumbling around inside my belly again this week, the news of each day sparking flints of anger inside me.

Continued atrocities in Ukraine, including hits on the southern region of Mykolaiv. One state’s rejection of 54 math books (namely for reasons of critical race theory). A celebrity pastor’s Easter post, as endorsed by an elite clothing line.

These, of course, are acceptable forms of anger: I am allowed to get mad on behalf of other people. When dictators destroy entire peoples, cultures and lands, it is okay for me to feel anger. When fear wages a political war in the name of “protecting our children” that hinders future generations in more ways than one, I am allowed to express anger. When the name of Jesus is made synonymous with wealth and affluence, as if God can be equated with luxury and freedom, righteous anger is a holy response.

Whether or not these examples spark anger in you, they are made acceptable for me because they are not of me.

Additionally, when systems designed to benefit all, actually, only benefit some, and I dig my heels in to advocate for those who have been wronged, then I am allowed to get angry. When wrongful hate crimes rise by 339 percent nationwide toward the Asian American community, and I dig my heels in and take a stand for justice, then my anger is justified.

Then, my anger may even be praised.

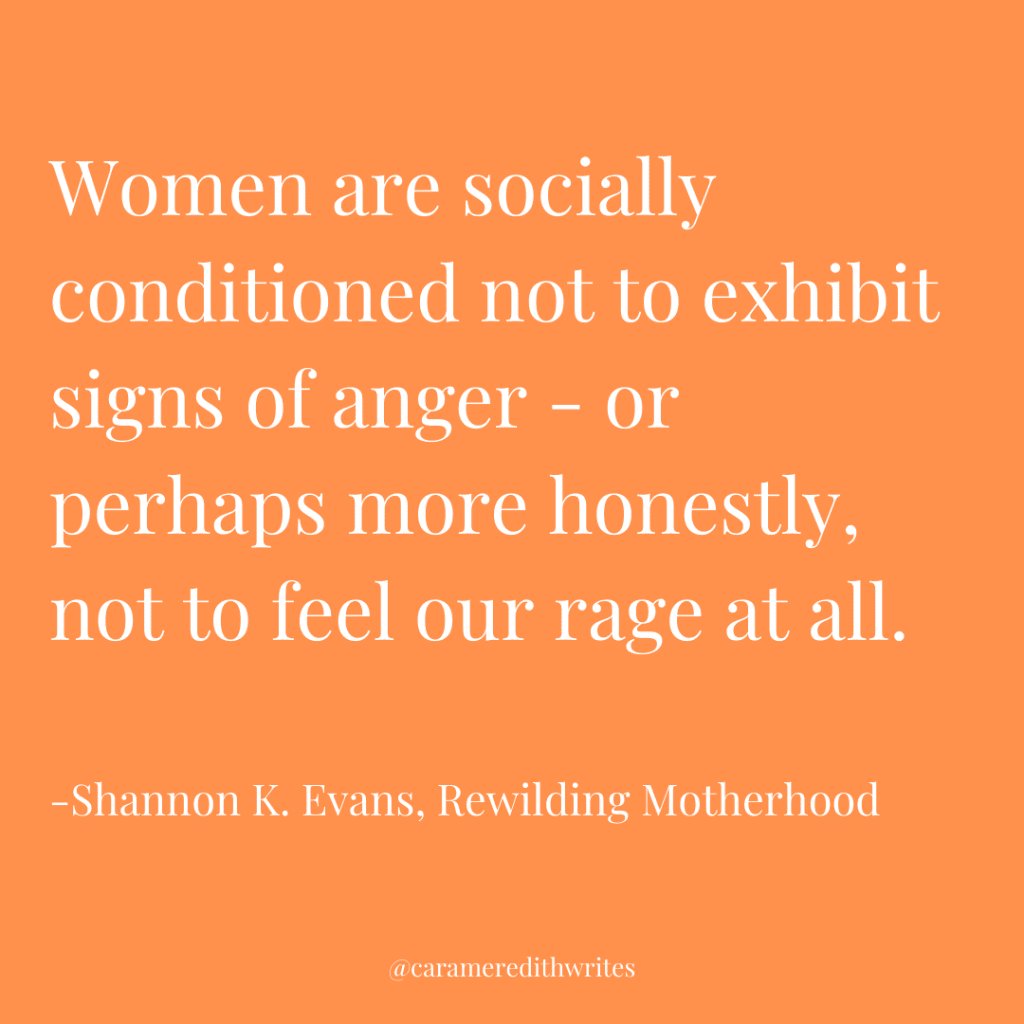

Too often, though, “Women are socially conditioned not to exhibit signs of anger – or perhaps more honestly, not to feel our rage at all,” Shannon K. Evans writes in Rewilding Motherhood.

As a white woman, I have been socially conditioned to run from anger, to subdue anger, to ignore anger, to suppress anger, and to not feel anger, in general.

Whether or not we actually, healthily express our anger, anger is a real emotion, alive and well inside each one of us.

And anger, even though it’s been there all along, is something I’m just now learning how to express – as a Christian, as a woman, as a white person, and as a human, in general.

Evans goes on to quote author Sue Monk Kidd, who speakings of transforming rage into rage. After all, “Rage is internal: a ball of fiery emotions held captive within us that, left to simmer too long, can lead to physical and psychological ailments and bitterness. What rage needs is to be transfigured into outrage.”

When this happens, anger no longer simmers inside us, bubbling up underneath the surface. Instead, and as Evans goes on to say, we wake up. We find ourselves disturbed by the status quo. We seek wholeness, for ourselves and for the world around us.

We do something, one might say, about those angry feelings that are already alive and well within us. We act on the fire inside.

We practice outrage, as Kidd writes in The Dance of the Dissident Daughter, for:

Outrage is love’s wild and unacknowledged sister. She is the one who recognizes feminine injury, stands on the roof, and announces it if she has to, then jumps into the fray to change it. She is the one grappling with her life, reconfiguring it, struggling to find liberating ways of relating.

And, God, isn’t this freeing? Isn’t this coloring outside of the lines, finally?