One of the hallmark features of Western culture is a widespread preoccupation with the notion of “competition”. In virtually all sectors of society — industry, economics, technology, education, governance, international relations, sports and other entertainments — there seems a relentless need to rank things, and to determine who or what is the “best” — the “winner”. Accordingly, many of our most important social institutions are designed to operate around this dynamic.

Competition has unquestionably played a critical role in birthing the world we know today — taking life from a few chains of nucleic acids to an entity capable of photographing its home planet from the edge of the solar system. Yet at this stage in the evolution of culture, is this still the best way to organize a society? I propose it is not. The competitive impulse may be in fact becoming an impediment to our further evolution as a species.

On first thought, there is a common rationale for our ongoing commitment to the competitive principle. As a living species, we seek ideally to realize our full potential — to be safe and to do the most we can with the gift of our existence. To achieve this, it makes sense to find the smartest, strongest, and most creative people who can teach and lead us toward taking best advantage of opportunities, and to develop the most effective solutions to the various threats and challenges we face.

However, consider also that humans are a social species. Few of us, even the most adept, are willing or able to live as a lone survivalist in the wilderness. In today’s world, we depend upon a myriad of others to grow food, weave clothing, build housing and other infrastructure, do medical research, provide healthcare and all the other accoutrements of a modern society. Moreover, most contemporary Western cultures profess values of equality and democracy — “one person, one vote”, “a level playing field”, “all equal in the eyes of God”.

Yet contrary to this, the structure of relationships in a competitive system is always a pyramid — start with the many and end up with the one. (Note for example the successive rounds of “eliminations” as charted in many sporting events.) This is in principle directed toward finding the single best among many. Once the “winner” is identified, all of the rest (technically the “losers”) tend to be treated as irrelevant (or at least don’t get the sponsorships and TV commercials).

Consider the Olympic competitions as an extreme example. While the games may be wonderful for generating international bonhomie, consider the premise that, of the world’s seven billion people, there is only one best skier/ swimmer/ marathoner who is deserving of the top award.

Were this competitive principle to be carried to logical conclusion in all sectors of society, we’d end up with a world populated by perhaps several dozen people and hoards of human irrelevancy (except to the extent that the latter may be useful to the former). I propose this organizational model is not the most functional and effective way to manage a large, modern, complex, and interdependent society.

Scarcity and Competition

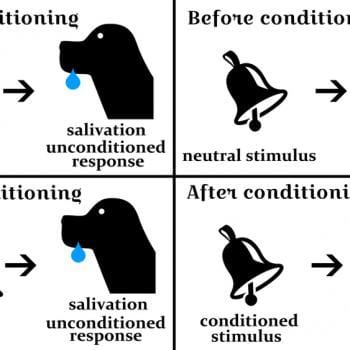

In earlier historical times, when food and other necessities were often scarce or unpredictable, the ability for a person or tribe to be an effective competitor was clearly a survival advantage. Competition determined which persons, technologies, and philosophies were “fittest” (in the Darwinian sense) for the prevailing conditions.

Yet owing to the vast array of knowledge, technology, and resources available in the modern world, survival today need not be an issue for anyone, anywhere, were our resources properly managed. Today, our competitions are largely over symbols, in pursuit of symbolic victories. Republicans vs Democrats, Ford vs, Chevrolet, Lyft vs Uber, one sports team vs another — none of these are essential to survival. (Acknowledging however that, if there is universal belief in the power of a symbol – money or national identity for example – life threatening consequences can follow.)

Simple versus Complex Systems

Again, in earlier times, social structures and technical processes were generally simple, involving few variables. Under such conditions, “best”, can be determined with reasonable validity. Whoever gets there first is “fastest”. Whoever lifts the most is “strongest”. Whichever farming practice brings the greatest yield is “best”. Who survives the battle is the “champion”.

Today however, along with the complexification of culture, any competitive person or system is affected by a far greater range of factors. Things or people who perform well in one context or environment, may not do well in another. Climate, geography, education, social networks, cultural mindset, timing, energy sources, ecological factors – and a host of others may affect the way something performs. Not to single out the Olympic competitions in particular, but does anyone believe that if the same contests were to be run on multiple dates, that exactly the same rankings would occur? Or if the world’s populace at large were included, that dozens of gold medals might need to be awarded?

If not Competition, then What?

In brief, this paper is intended to question several principles or assumptions that drive much of our culture — yet operate largely unconsciously:

1) People will perform at their optimum only under threat (greed and dominance being secondary responses to fear/threat)

2) It is essential to find the “best” in every context

3) Competition is the best way to do so

4) Once the best is determined, everything else can be discarded as irrelevant

If we are in fact a social species, living in a complex, interdependent society, one does not have to connect too many “dots” to see the unsuitability of the above model. A complex system – the human body for example – works best when all components are considered valuable, attended to, and supported toward serving their function for the health of the whole system. The heart cannot survive at the expense of other organs. In contrast, there is a biological system that seeks to maximize its own well-being without regard to its larger environment. We call it “cancer”.

Finally, competitive systems have a built-in limitation — one never exceeds the abilities of the winner (otherwise, he, she, or it would not be the winner). The best that the one has to offer is the limit of what can be — unless an infinite string of new winners can be found. By contrast, the power of collective intelligence and effort can under the right conditions be an exponential advance. That’s why lone geniuses are rare, and most innovation tends to come from small groups or companies.

Yes, I know human culture is virtually crack-addicted to competitions — Super Bowl, Emmys, America’s Got Talent, races, spelling bees, politics — and that basic Chaos Theory holds that it is hard to imagine a new paradigm from the vantage point of the old. But I hope you will at least hold some mental door ajar for the possibility of a newly emerging society wherein every member is valued, and can be supported toward realizing their potential — without the requirement that someone else must fall behind in order to do so. What might then be possible?

Our current tendency is to always view life as a zero-sum game. Let’s play a new game!