When I say that I do not believe free will has any reality other than our immediate experience of it, that is not to say that I do not think we experience degrees of freedom. I do believe that causal forces (physical environment, genetics, quality of life in utero, how we’re raised, how we’re schooled, etc.) do ultimately all weave together—however subtly and complexly—to determine the decisions we make; however, we definitely experience greater and lesser degrees of freedom. (A friend of mine suggested, “Perhaps natural selection has allowed for a brain that loosens instinctual responses, thus allowing for higher levels of cognitive flexibility.” Yes, human beings are capable of making decisions that are more subtle, nuanced, and refined than blunt instinct tries to dictate.) To illustrate: Child A is born to a malnourished woman in a third world country, doesn’t attend school, and carries cinder blocks for pretty much his whole childhood. Child B is born to a healthy, well-to-do family in a first world country and is thoroughly educated in well-funded schools. I do believe that both of these people are without free will—that their decision-making is ultimately determined by prior forces, but I also believe that the second fellow is more “free” in that the forces “behind him” weave together into a life that is fuller and brings him closer to human flourishing (eudaimonia) than the first fellow. If the first fellow could experience the life of the second fellow, he would almost certainly choose to switch places with him, while the second fellow would almost certainly not switch places with the first. Or, more radically, would you rather be a prisoner in a Soviet gulag or be a traveling poet in western Europe? One is unquestionably preferable because you’re more “free.” I do not see a conflict between having a wide range of freedom while having no “free will” (paradoxical as that at first might seem).

Now you ask: Why should we choose to live and not end it all in an absurd, meaningless universe? To that I have two responses: First, if we admit that death could mean total annihilation, then death is preferable to some states but not to others. If I were experiencing extraordinary anguish from which no recovery appeared possible, I might possibly choose death over that. But it seems to me that for most people, life in general isn’t so awful. Feeling the sunshine on my skin and listening to music, for example, seem net-positive experiences—meaning preferable to the nothingness of death, so why not live for those experiences? My God, if we’re all headed to the grave one way or another, I can see no reason not to extend the experience of “worldness” a little longer—absolutely no reason not to!

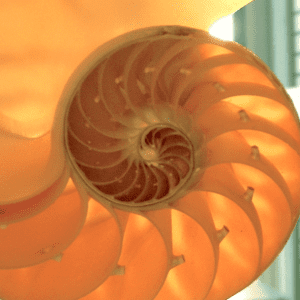

But there’s a question: if ultimately there is no self and no free will, then is everything just random and meaningless? It’s possible, but it doesn’t appear that that’s the case. I really have been thinking this one through, and I think whoever came up with the “Transcendentals” of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty (I believe Thomas Aquinas was the major proponent) had it right—and by these three I am not claiming that there is any “absolute” truth/goodness/beauty (though there might be, as people of faith are confident), but I will say that in those three categories there can be more or less of it. Regarding truth: if the armed forces kill a thousand civilians during a war but say they only killed ten civilians, for whatever reason—say, to preserve institutional reputation, doing so is definitely worse than disclosing that they indeed killed a thousand, regardless of the consequences for doing so. Don’t get me wrong—I realize that there are (unusual) cases when concealing the truth is justified—like the proverbial “hiding Jews when the SS comes inquiring at your door.” Regarding goodness: it is better to feed, raise, and educate a child than it is to lock him up in box or starve him. Human flourishing is essentially always preferable to human stuntedness, despair, and misery (and this should be extended to encompass all higher animals). Finally, there is better and worse regarding beauty—perhaps not with whether a painting by Paul Gauguin or Georges Seurat is better, or whether Johann Bach or John Coltrane produces better music, but for God’s sake if you had to tell me which is the more beautiful: an Appalachian mountain before or after having its top blown off and strip-mined, let’s soberly admit the correct answer—the former. Could we, with a photographer’s eye, find some beauty (perhaps symmetry or shadow) in the strip-mined mountaintop? Sure, but the mountaintop prior to being ravaged is more beautiful, just as the face of a woman is more beautiful before her horrible husband strikes and bruises her. I will not accept that there is total relativism in beauty.

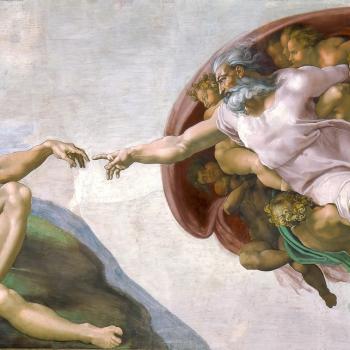

Finally, I feel Rilke nailed it in 1903 when he wrote:

“Why don’t you think of God as the One who is coming, who has been approaching from all eternity, the One who will someday arrive, the ultimate fruit of a tree whose leaves we are? What keeps you from projecting his birth into the ages that are coming into existence, and living your life as a painful and lovely day in the history of a great pregnancy? Don’t you see how everything that happens is again and again a beginning, and couldn’t it be his beginning, since, in itself, starting is always so beautiful? If he is the most perfect One, must not what is less perfect precede him, so that he can choose himself out of fullness and superabundance? Must he not be the last one, so that he can include everything in himself, and what meaning would we have if he whom we are longing for has already existed?” (Letters to a Young Poet—letter #6, trans. S. Mitchell)

So this is my current view of reality: For whatever reason (cue Kant on space and time) while we live, we experience the unfolding of a universe “toward” some end that is wonderful, and we can only trust that that end (what Rilke describes above) is wonderful because we experience truth, goodness, and beauty now and we also experience ourselves defending and advancing them—that they somehow matter in a fundamental sense. I could say, “Well there has been and continues to be so much misery in the universe that it’s clearly all a waste or a sick cosmic joke,” but for some reason, in my actual lived life, I nevertheless contemplate the truth of things, seek the camaraderie of friends, and participate in decisions that move things toward flourishing rather than wretchedness. Somehow a set of forces weaves together to produce all that’s wrong and flawed with me but also all that’s noble and thirsty-for-truth in me.

I’ll close by saying that I am not certain of any of the above; I am at least confident that some of it is the case, but I am not certain, and I’m also not going for some Hegelian totality. I’m just trying to put together what seems like the most thoughtful and fruitful view of the world based on what I’ve so far learned. And I am repelled by people who seem so certain of their beliefs. The same friend I quoted in the opening said to me, “We are adrift. Maybe all attempts at coherence end in idolatry or ideology.” I agree that we might be adrift, but there is coherence of some sort in reality; even putting words together at this moment is evidence of it. But a question remains: Can we proceed in some way that is neither idolatrous, nor ideological, nor completely relativistic? (Surely there is something “between” those extremes?)