According to Thomas Aquinas, we can know things in three ways:

- Directly, as we know the things we see around us.

- Indirectly, by reasoning from the things we see around us.

- By revelation from God.

The first category—the things we know by direct experience, as I know the keyboard on which I’m typing and the desk it sits on—would go without saying if it weren’t for the persistent influence of Descartes’ methodological doubt and the absurdities of those who followed after him. As for me and Thomas, we accept objective reality as a given. (Yadda yadda yadda, brain in a jar, yadda yadda yadda: I’m not buying it.)

Second, we can learn many things by reflecting on the things we know by direct experience, and by reasoning about those things.

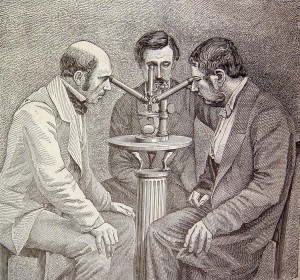

Scientific knowledge, properly understood, is a combination of these first two categories. It is always based on observation of things as they are, possibly with the help of complex instruments such as microscopes and supercolliders; and it is always based on reasoned abstraction from those observations. Newton did not observe that Force = mass times acceleration; he observed objects in motion, abstracted from those motions the notions of force, mass, and acceleration, hypothesized that the equation F = ma described the relationship between them, and found that in the examples he saw around him that F = ma was a good fit to the data. Similarly, Ptolemy was trying to predict the motions of the heavenly bodies. He proposed a model, based on observations taken with the naked eye, and found that it did a good job of predicting them—such a good job that it held up for over a thousand years, until better observations made with telescopes were available. (Michael Flynn has told the story of the Great Ptolemaic Smackdown in painstaking but fascinating detail; highly recommended.)

Scientific knowledge, properly understood, is a combination of these first two categories. It is always based on observation of things as they are, possibly with the help of complex instruments such as microscopes and supercolliders; and it is always based on reasoned abstraction from those observations. Newton did not observe that Force = mass times acceleration; he observed objects in motion, abstracted from those motions the notions of force, mass, and acceleration, hypothesized that the equation F = ma described the relationship between them, and found that in the examples he saw around him that F = ma was a good fit to the data. Similarly, Ptolemy was trying to predict the motions of the heavenly bodies. He proposed a model, based on observations taken with the naked eye, and found that it did a good job of predicting them—such a good job that it held up for over a thousand years, until better observations made with telescopes were available. (Michael Flynn has told the story of the Great Ptolemaic Smackdown in painstaking but fascinating detail; highly recommended.)

But though Thomas would certainly have supported the scientific method, as it later came to be understood (his master, St. Albert the Great, was the greatest scientific observer of his day), he went beyond that. In addition discovering the proximate causes of the events and phenomena in front of us, he believed (with Aristotle) that there were ultimate principles that could be discovered by applying logic to fundamental truths and observations of nature. One of these ultimate principles, according to Thomas, is the existence of God, and a handful of facts about Him. These, he thought, could be objectively and rigorously proved.

I am not attempting to prove this here, mind you, as it’s a lengthy chain of reasoning, and though I’ve followed it I’m not at all confident of my ability to present it accurately. I’ll simply note that Aquinas’ famous “five ways”, found in his Summa Theologiae, are proof sketches, rather than full-fledged proofs, and depend on a shared philosophical (not theological) understanding that derives from Aristotle’s Physics and Metaphysics. I may have some words to say about those at a later date.

Still, Aquinas’ proofs about God, what is called his “natural theology”, do not go very far, and are more about what we cannot say about God than what we can. To go farther we need revelation. God’s revelation to us, through Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, through Moses and David and Solomon, and ultimately through Christ, shows us a God, creator of all, who wishes to make Himself known to us.

Aquinas did not hold that we could prove the truths of “revealed theology” as we could prove the truths of philosophy and natural theology. But one of the things Aquinas shows in the Summa is that God is not simply a speaker of truth, but Truth itself. God is not, therefore, a liar: everything He does is consistent with everything else. As He is the creator of the natural world, and the author of revelation, then, these two things cannot ultimately be in conflict. (This is why the Church accepts the fossil record and doesn’t generally support Young Earth creationism—if the earth is young, the fossil record would seem to be a kind of lie.) Thus, in the Summa Aquinas operates in two distinct modes:

- He proves what he can prove (natural theology)

- He refutes objections to proposition of revealed theology

In short, when I tell you that Christ is the Son of God, the incarnation of the Second Person of the Trinity, I cannot prove to you that this is the case, either on scientific terms or by the kind of rigorous philosophical demonstration that Thomas favored. What I can (in principle) show is that it is not logically inconsistent with what we can know without revelation. (I say “in principle” because though I’ve been studying up on these things, as a philosopher/theologian I remain a pretty good software engineer.)

And that brings us to faith, which is not a blind acceptance of logical propositions, but trust in a person, Jesus Christ. You don’t need to know (or be able to articulate) everything about a person to know that they are faithful, that is, trustworthy. And because they are trustworthy, you can take what they say “on faith”. What Catholics mean by the God-given gift of Faith is this ability to trust in Jesus Christ.

I cannot argue you into this kind of faith, no matter how hard I try. All I can do is to do my best to introduce you to Jesus Christ himself; and ultimately, you have to ask Him to introduce Himself. Marshall McLuhan did this, as Julie Davis related recently. He prayed, “Lord, please send me a sign.”

He asked sincerely, and God answered.

____

photo credit: El Bibliomata via photopin cc