My theological analysis of Thomas Kinkade’s work (“The Dark Light of Thomas Kinkade”) was an attempt to make sense of my abiding discomfort with his work as well as respond to my dissatisfaction with the commentary it has generated over the years. Neither his supporters nor his critics have offered compelling arguments. In fact, a virtue of Kinkade’s work is that it poses a stiff challenge to those advocating “Christian art” and those defending a purely secular understanding of artistic practice, including old saws about what makes a work of art “good.”

It is inevitable, as an art historian and a theologian of culture, that in attempting to follow St. Paul and take every thought captive (2 Cor. 10: 5), I run the risk of over-interpretation, finding theological significance under every aesthetic and cultural rock, some of which might better be kept unturned. Yet it is a risk I am willing to take. Visual images, including works of art, are not passive and harmless. They exert their presence, demand recognition, and shape us, whether or not we are aware of it. They do so because they are aesthetic artifacts of human intentionality, bringing us in relationship to embodied thought, feeling, and action. Last week I suggested that Kinkade’s quaint and nostalgic images, as pleasant as they seem to be, are dangerous, offering a comfortable world that silences the two words with which God speaks to us (law and gospel). The world isn’t so bad, faith isn’t so hard, grace therefore not so desperately sought. Following Michael Horton, Kinkade’s desire to depict a world before the Fall is Christ-less Christianity in paint.

I would like to go even further and suggest that it was Kinkade’s work that killed him. It was not a weak heart or too much alcohol that caused his sudden death at 54 on Good Friday, but the unrelenting pressure that the production and distribution of these images exerted on a man who spent thirty years trying to live up to their impossible and inhuman standard. His emotional life found no creative release in and through his studio work. As he, like each of us, experienced the ebb and flow of life, the challenges, tragedies, and the struggle with personal demons, he was forced (condemned) to produce the same, innocuously nostalgic pictures again and again, fighting on one hand to preserve a brand as the Painter of Light, while he fought to the death his own demons on the other. These seemingly gentle images came to exert a claustrophobic spiritual pressure on him that rivaled anything that Munch, Picasso, or any other modern artist has produced. It is a pressure that, as Luther observed in his commentary on Jonah, “makes the world too narrow” so narrow that “a sound of a driven leaf shall frighten them” (Lev. 26: 26)–a driven leaf or a Kinkade print.

“The best way out is always through,” wrote Robert Frost in “A Servant to Servants” (1914 ). Whether in words, sound, movement, paint, or bronze, artists give form to their joy and grief, searching out their doubts and questions through their studio work. A painter like Gerhard Richter, a photographer like Cindy Sherman, lyricist and poet like Leonard Cohen, musicians like the Cowboy Junkies, and writer like Toni Morrison, produce work that shifts and changes as they themselves shift and change, and as they walk through the valley of the shadow of death (Ps. 22: 4). Not so for Kinkade. He became a prisoner of a pre-Fall fantasy world that by refusing him creative space to work through his life’s difficulties, destroyed him, over and over, to which he finally succumbed.

Hans Holbein’s Dead Christ, which fascinated Dostoyevsky and horrified Prince Myshkin, is a predella without an altarpiece; a depiction of the dead Christ in the tomb without the resurrection to give it meaning as Holy Saturday. Although his work refused to confront and work through evil and brokenness, our lived reality, Kinkade himself did. It is not insignificant that he died on Good Friday. For Kinkade, as for each of us, our lives are hidden in Christ, who rose on Easter Sunday, reconciling us and establishing the work of our hands (Ps 90: 17). For in fact, every work of art, whether Holbein’s Dead Christ, Munch’s The Scream, Damien Hirst’s stuffed shark, or Kinkade’s pictures, is made in the shadow of the resurrection. An artist once told me that he considers every painting he makes to be a diptych (a two-panel painting). The second panel is always a mirror, scrutinizing him as he paints it.

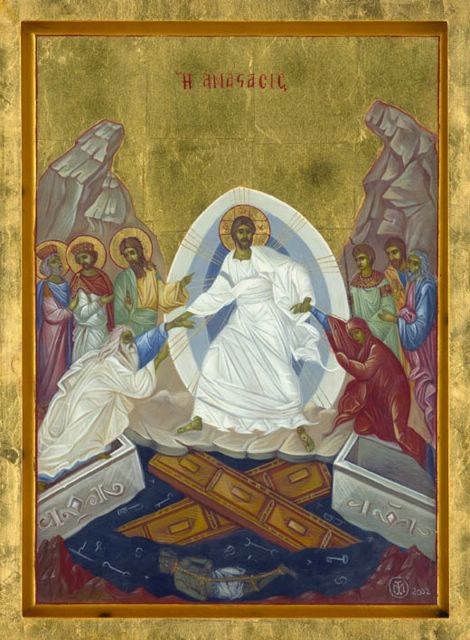

It might be better to think of that second panel not as a mirror, but as an icon, an icon of the resurrection. Commonly called The Anastasis, the image depicts Christ bursting forth from the grave, having descended into Hell on Holy Saturday, “leading a host of captives” (Ps 68:18; Eph. 4: 8-10). The power of the icon comes from Christ liberating the dead from their tombs by taking them (you and me) by the hand. It is this for which Christ came. “He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives/ and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed…” (Luke 4: 18).

Christ also frees our work, including our art and culture making, liberating it to glorify God and serve our neighbor, rather than means for our salvation or justification, as metaphysical transactional leverage. In captivity, “the world becomes too narrow for us.” Christ opens up the world, the world of experience, action, making. He does so because, as St. Paul writes in his letter to the Colossians, “all things were created through him and for him” and “in him all things hold together” (Col. 1: 15; 17). And that includes Kinkade’s work, even if he was unable to reconcile the creative work of his hands to his daily struggle as a Christian. In Living by Faith: Justification and Sanctification (2003), Oswald Bayer writes,

“Justification comes when God himself enters the deadly dispute of ‘justifications,’ suffers from it, carries it out in himself. He does this through the death of his Son, which is also God’s own death. In this way God takes the dispute into himself and overcomes it on our behalf.”

Kinkade and his work engaged in a deadly dispute over justification, which he lost. But the final word on Thomas Kinkade is not his work’s. Nor is it mine. It is God’s, who offers the final Word of liberation and freedom. The next time I notice a Kinkade print in an office or a home, I will now see it next to the icon of the resurrection, reminding me that Christ is at work reconciling “all things” to himself, and second, I will give thanks that the work of my own hands, which in its own way deceives and distorts, judges and condemns me, narrowing my own world, will receive God’s final Word as well.