I recently spent the weekend with artist Makoto Fujimura at his new studio in Princeton, New Jersey, and in the course of our conversations, some of which were videotaped for a documentary, we discussed the presence of grace in artistic practice. Grace, which is undeserving, one-way love, is disruptive, counter-intuitive, and operates against our fallen human nature because it wrecks our conditional economy that finds meaning and significance in transactions. However, painters, writers, and musicians seem more sensitive to its presence and its violent implications than the rest of us, especially those of us who happen to do theology and cultural criticism. Yet my conversations with Fujimura revealed much more. To experience a painting is also to be on the receiving end of the violence of grace. A work of art is brought into existence through a long, arduous, and often painful process, and then given gratuitously and undeservingly for another, for me. A work of art speaks, and as the viewer, I listen. We look at a painting, but what we are really doing is listening. Grace comes through speech. It comes through our ear hole. And we must hear it before we can see it.

There is a saying in the art world that collectors, curators, and dealers see with their ears. They respond first to the buzz and gossip surrounding the artist and that determines what they see when they look at his or her work. Although it is intended to reveal the shallowness of the business of art, it discloses a profound yet overlooked theological and aesthetic truth. It is with the ear, not the eye, that reflection on art begins. Most modern Protestant and Catholic theological reflection on art begins with the dichotomy of text and image. Yet neither is foundational. It is speech, the Word of the Lord that creates the cosmos, that comes to his prophets, that comes in Christ as a promise–I love you, I forgive you, and lo, I will be with you always even to the end of the age. That is grace and it comes through speech.

Luther rediscovered the sacramental nature of speech by recovering God’s disclosure of his promise of grace through preaching, through the preached Word of forgiveness, mercy, grace. Preaching conjures negative connotations in the modern world, and not without good reason. It brings to mind the hellfire and brimstone of Jonathan Edwards, the anxious bench of Finney, the self-help feel goodism of Joel Osteen, and even the dry as dust verse by verse lectures that masquerade as sermons. But Luther meant something very different. God’s promises needed to be spoken into the ear holes of those who believe that it is too good to be true. Preaching is the material embodiment of God’s grace, his own words of forgiveness to us that despite every evidence to the contrary, in nature, culture, and in our hearts, his promises are true.

For Luther, preaching as the communication of God’s promises, discloses the world in all its enchanted beauty and aesthetic richness. On September 8, 1538 Luther gave a remarkable sermon on Jesus’s healing of the demon-possessed deaf and mute man in Mark 7: 31-13, the gospel reading for the Twelfth Sunday after Trinity. (I discuss it in some depth in my first blog post, The Scream and it will no doubt reappear often.) Jesus recreates the man by opening his ears and sighing “Ephphatha!” (be opened!). This recreation, in which Jesus uses material (the spittle that he places in the man’s blocked ears with his fingers) opens him to “hear” the world, turning him toward the world, unlocking him from the prison house of his own head. For Luther, preaching, baptism, and Holy Eucharist are sacramental, they are material means by which God brings his promises to us–spitting on his fingers and sticking them in our ears and sighing, be opened! Whether through wine, bread, water, or the voice of the preacher, God is preached through matter, and as we taste and see, we do so all the while hearing the Word spoken to us.

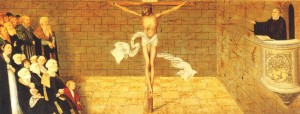

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Wittenberg Altarpiece (predella), 1547

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Wittenberg Altarpiece (predella), 1547

In his reflection on Luther’s sermon, theologian Oswald Bayer writes,

The most surprising point in the entire sermon is that Luther, without digressing and in a theologically bold way that is most strange to our ears, takes the Word that Jesus Christ himself speaks in the miracle story and claims it as a Word that every creature speaks to us (Martin Luther’s Theology: A Contemporary Interpretation, 114-115).

For Luther, the whole world speaks: “Sheep, cows, trees when they bloom, say: ‘Ephphatha’.” The world speaks, yet without the proclaimed, sighing Word to open our ears, we are deaf to it. For Luther, “Creation,” as Bayer argues, “is the promised world.” It is an article of faith and is disclosed as creation only through Christ, the preached Word, God’s promise, which opens our ears, and by so doing, transforms what we see and what we make of the materials of the world, including oil paint and canvas.

Makoto Fujimura and the author at his studio in Princeton, New Jersey

Makoto Fujimura and the author at his studio in Princeton, New Jersey

But what of painting? Our conversations about art and grace took place in front of a painting, Golden Sea, that Fujimura had wanted me to see for some time. It is a painting with an unusual story. As he was at work on an ambitious painted manuscript project for Crossway publishers, called the Four Holy Gospels, Fujimura would take a break by painting on a canvas in the corner of his studio–a form of absent-minded relaxation from the rigors of the illumination project. Yet visitors to his studio whom he had expected to show examples of his painted manuscript pages, were continually attracted to this form of play. The painting began to declare its presence, speaking to visitors in the studio. Finally, Fujimura began to be attentive to the work, listening and responding to it, and in the process realized that something special had been occurring without his awareness. The result is a painting that to his mind marks a culmination and a watershed in his development as an artist. In an essay on his studio practice, Fujimura writes,

The process of creating renews my spirit, and I find myself attuned to the details of life rather than being stressed by being overwhelmed. I find myself listening rather than shouting into the void. (“A Second Wind,” Refractions, p. 15).

At important moments, making a painting becomes passive; it involves responding, listening, waiting. The Scriptures reveal to us that we are perpetually prone to look for God in impressive monuments, great whirlwinds, massive visual displays of his glory. Yet God reveals himself in the still small voice, the timid and reluctant mouths and brokenness of his prophets, the humiliation of God preached. We are most definitely created to wait on this Word, waiting for a message (messenger) of hope from beyond the hills, waiting for Godot, even if we are, like Hermann Hesse, convinced it (He) will never come (“I wait, I sleep, I die.”).

It is the artist, the writer, the musician who gives form in countless ways to this absurd hope that clings to all of us. A painting in the world, whether Munch’s The Scream or Fujimura’s The Golden Sea, speaks, saying, “be opened!” It does so because God has not been silent. What must we do? Believe that Word.

And that opens our ears so that we can see.