Poet and Editor Aleksandr Tvardovsky

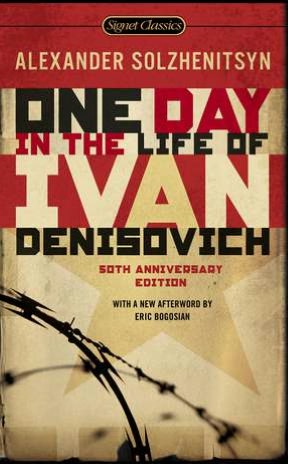

It was Aleksandr Tvardovsky’s habit to lounge about his apartment in his bathrobe looking at the manuscripts that littered his living quarters. As editor of the liberal magazine Novy Mir in the Soviet Union during the height of the Cold War, Tvardovsky was well known as a Soviet poet as well as a staunch defender of his literary magazine’s independence. One morning he came upon a manuscript and began reading. He then stopped, put the manuscript down, took a shower, shaved, put on his best clothes, and drove to his office to finish reading it. The manuscript? It was “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who wrote it in secret in the late 1950s. Tvardovsky was so moved by the manuscript that he convinced Khrushchev to publish it and it appeared in Novy Mir in serial form in 1962. Solzhenitsyn would go on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature several years later. This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of its publication.

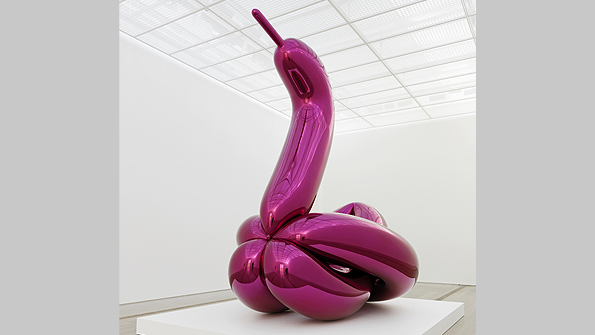

It is easy to see how Solzhenitsyn is the hero of the story. But it is the editor Tvadovsky who recognized its brilliance amidst the clutter of competing manuscripts and fought for its publication, at great cost to his career and even his life. The poet Osip Mandelshtam once said that the Russians take their poets seriously, they shoot them. (Mandelshtam would himself experience that seriousness.) This story demonstrates the need for discerning critics, curators, and editors with the sensitivity to recognize significant artistic achievement and the courage to promote it, whatever the cost, within their spheres of influence. This is especially so in our autistic, distracted, and amnesic cultural moment, where quality and success is defined by the phrase, “going viral,” Jersey Shore dominates cultural discourse, art dealers prowl undergraduate art departments on the coasts to find the twenty-somethings with the next signature style, and Jonathan Franzen’s novels are considered serious literature. In a recent article in The Economist, Jeff Koons’s new work is celebrated as “speak[ing] to a global elite that believes in the holy trinity of sex, art and money. Art collectors enjoy seeing themselves reflected in what they buy.” Great art, literature, and music is being produced, but there are more distractions and clutter that obscure it and more effort is needed to support it.

Evangelicals have been largely content to participate in culture in a narrow, negative, oppositional way, railing against art that supposedly undermines a “Christian worldview,” obsessing about four-letter words in music and movies. Yet we also possess a well-earned reputation for the production of mediocre-to-atrocious art and culture, from Thomas Kinkade, Warner Sallman, CCM to the Left Behind franchise, and countless artifacts from “Christian artists” that are nothing more than thinly-veiled propaganda.

It is clearly not enough to make culture, all of us make culture—that is what we do, which Andy Crouch has brilliantly demonstrated in Culture Making (IVP, 2008). Evangelicals have a responsibility to support great art and culture, to support art and culture that will last beyond the news cycle, the fall season, even the current generation of consumers. When asked what he would do today if he knew that the world would end tomorrow, Martin Luther responded, “I will plant an apple tree.”

Apple trees have been planted throughout culture, apple trees like Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich that take years to cultivate, requiring care and commitment beyond gauging the number of “hits” or “shares,” licking one’s finger and determining where the winds of fashion are blowing. Artists will continue to make significant work in the face of the noise and distractions. What are needed, however, are critics, editors, curators like Tvardovsky who recognize them and are willing to cultivate their work at any cost because they believe in their significance as works of art, as artifacts that give form to our humanity.

Jeff Koons, Balloon Swan, Stainless steel, 2012

Jeff Koons, Balloon Swan, Stainless steel, 2012

The world of culture–art, music, literature, film–is overrun by transactional artists who are less concerned about their craft and its capacity to give shape to the human condition than in chasing recognition—wealth, fame, power—like Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Thomas Kinkade, Jonathan Franzen, and Jerry Jenkins, who use “art” and “literature” to flatter and patronize their consumers. Yet the world of culture is also overrun by transactional curators, editors, and critics who chase these entertainers, who use them or allow themselves to be used by them to satisfy their own desire to be justified through wealth, fame, power. These curators, editors, and critics wouldn’t be caught dead not riding the current bandwagon or standing alone in support of a particular artist that appears out of step with current trends.

The contemporary cultural landscape needs Christian participation like never before. Not because art needs to be transformed, redeemed, remade into something “Christian.” In fact, the last thing culture needs is “Christian artists.” But rather, art needs to be protected and preserved by critics, curators, and editors who care about it for its own sake, as a humanizing practice that deepens our humanity, and is committed to preserve the Great Traditions of painting, film, poetry, prose, and music because they are a vital means of human expression. Christians who care about the arts must co-labor with anyone who shares their commitments. But perhaps it is Christians, who believe their identity is hidden in Christ, whose justification as human beings is defined by what Christ has done, not what they do, and thus have the freedom to resist the urge to use art as instruments of fame and power, who can recognize and support art that reveals the truth of our condition, our brokenness, while at the same time testifying to the alien presence of grace rustling about in the world, which comes from beyond the hills. Authentic art is nothing less than an aesthetic testimony to the promise of grace, and as such, deserves our utmost respect and our efforts to preserve it against forces that would distract us. We need to be cultural witnesses, willing to seek out and preserve authentic art, no matter where it is, and no matter how unpopular it might be to do so, bearing even the criticism we will surely receive from fellow Christians.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich exists in the world not only because one man had the courage to write it, but because another man recognized its greatness and had the courage to publish it.