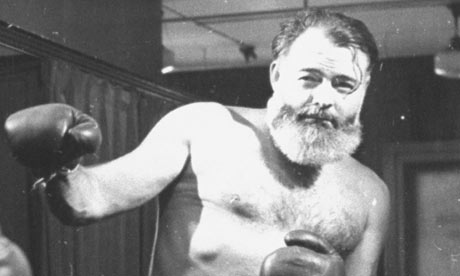

What is the relationship of the artist to the work of art? Is it merely the result of the artist’s intentions and nothing more—a visual, literary, or musical message sent to the viewer that contains the artist’s emotions, thoughts, worldview? This is a question that has long perplexed critics and Charles McGrath’s recent article, “Good Art, Bad People” in The New York Times, offers another dimension to this question. McGrath’s article focused on artists who have produced great art but have done so at the expense of their loved ones. McGrath reflects on this disjunction and asks, how can we appreciate the great work of greatly flawed men and women? Hemingway is his primary focus but it could have been countless others. Do their lives, that is, their immoral or criminal behavior, bigoted beliefs, and horrible treatment of friends and family disqualify the greatness of their work? Is the work of art forever tethered to the artist’s intentions and, by extension, to his or her seriously flawed character? And are we obligated to experience a work of art through the biography of the artist and interpret the work of art as an artifact of their broken lives (and abhorrent ideas)?

The popular understanding of art is that it is indeed a direct extension of the artist’s thoughts, emotions, worldview—indeed, his life. In fact, it is so direct, that one can even start with the work of art and extrapolate from it the artist’s thoughts. The presumption is that a work of art and its meaning is the product of precisely what an artist intends. This is often how “Christian worldview” thinking operates, taking the work of art and that work of art is merely aesthetic an extension of an artist’s intentional worldview.

We want artists to tell us, once for all, “what the painting means,” yet this is contrary to how artists understand their work (even as some go to great lengths to control the interpretation of their work). Abstract Expressionist painter Willem de Kooning once said that he painted himself out of a picture and T.S. Eliot observed that the meaning of a poem occurred somewhere between the poem and the reader. The artist brings all she has to the production of a particular work—emotions, thoughts, ideas but that completed work then faces the world and moves toward the viewer, reader, listener. It is not the artist but the work of art that is working on us, and what it offers to us is therefore much broader and deeper than the artist’s intentions, many of which she is only barely aware, if at all.

But this gap between the artist and his life, thoughts, and intentions, is theological. It is founded on the unfree will of the artist. We are trained to believe that art is about the expression of freedom. Although few would put it quite this way, artists recognize—through intuition and feeling—that they possess a radically unfree will. One of the many consequences of this unfree will is that it makes even one’s own heart a mystery. If my will is not free, it cannot be transparent to me, much less to anyone else. And artists by their own work as artists recognize this. Indeed their work is an attempt to search those unfathomable and mysterious depths of their own hearts and their own understanding. Artists make paintings, poems, stories, and song not to express what they already know and feel (evidence of a free will) but try to discover something about themselves they do not know. The work of art thus encompassing more of the artist than he or she is even consciously aware. Scripture is saturated with evidence that supports the prophet Jeremiah’s lament, “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick; who can understand it” (Jer 17: 9)? Artists, more than anyone else, are confronted with the convoluted mystery and frustrating opacity (and darkness) of one’s own heart, the impossibility of knowing one’s own intentions. Artists know they work with a radically unfree will when they finish a painting, stand back to look at it and realize it is doing something they not only did not expect but could not control yet reveals something profound about them while also disclosing our shared human experience of this fallen yet grace-filled world.

Only those who expect a work of art to make an artist’s beliefs, thoughts, and ideas transparent assume that the artist’s will is free, free to be known unambiguously by the possessor and then, through the work of art, by the viewer. But artists follow St. Paul, who made much of the war inside himself, that maddening disjunction between what he wants and what actually occurs, the confrontation of the old and the new Adam (Rom 7: 21-25), which made him incapable even to judge his own intentions (1 Cor 4: 3-4).

That we do not and cannot know our hearts is a source of liberation for those who know that their hearts are known fully only in Christ (1 Cor 13: 12). And it is what gives great works of art their capacity to transcend the limits of their makers (and their deceitful hearts), opening up a space that allows the viewer, reader, or listener to discover unknown regions of their own hearts. Contrary to everything we’ve been taught, the very existence of art is a witness to our unfree wills and a promise that they will one day be free, a promise that we can be fully known.

While we lament the radical and heartbreaking disjunction between the darkness of an artist’s life and the light of his work, we give thanks nevertheless for that light, which shows us, if only momentarily, beauty in the face of ugliness, clarity in the face of chaos, and freedom in the face of slavery.