Claudia Alvarez, Flower Girl, ceramic, 2011

Art is like a magnet, attracting, collecting, and accumulating our thoughts and experiences over time. This process peels back new layers of the work, which those thoughts and experiences seem to reveal. A good work of art interprets us, works on us, forces itself on us and invades our thoughts, getting into our psychological nooks and crannies, insinuating itself into our emotional lives, and often forcing us to confront the reality of our lived experience in particularly powerful ways.

Claudia Alvarez, Falling Rope of Silence, Installation, 2011

Claudia Alvarez, Falling Rope of Silence, Installation, 2011

Over the past few weeks the work of New York-based artist Claudia Alvarez has been interpreting me. But I did not realize the extent to which it has penetrated my inner life until yesterday at Coral Ridge Presbyterian Church, when Dr. Jono Linebaugh, professor of New Testament at Knox Seminary, who delivered the sermon, asked, “What does Christmas have to say to the slaughter of babies under Herod, to the atrocities in Newtown?” And so I thought I would reflect on her work in the light of that sermon and recent events.

Claudia Alvarez, Juntos, 2005, oil on canvas, 72″ x 48″

Claudia Alvarez studied art at the University of Cal-Davis and at the California School of Arts and has worked as an artist in residence in Mexico, Switzerland, France, and China. Her work has been exhibited throughout the United States, Europe, and Canada. Her artistic project is exclusively concerned with children. And they have haunted since I first saw them ten years ago when I was serving as a residency juror at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art in Omaha, Nebraska. Art work that features them are often (usually) didactic and moralistic or trite and kitschy. And it is easy to understand why. Children elicit our strongest emotions, our most passionate responses to and hopes for this world. They embody our hope that the world really is, down deep, good. It is the world of Christmas morning. But Alvarez’s work offers us something else, what C.S. Lewis wrote about Narnia under the rule of the White Witch—it is always winter but never Christmas. This is what we want to protect our children from—from our fear that there really isn’t Christmas. But Alvarez’s work refuses to play along.

Alvarez’s children are strange—they look like children but they don’t feel like children. They are harsh. It is not hard to imagine that Victor Hugo’s description of the young orphan, Cosette, in Les Misérables, applies to these creatures: “injustice had made her sullen, and misery had made her ugly” (p. 157).

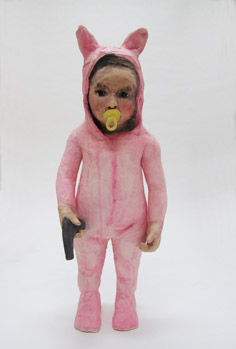

Claudia Alvarez, El Chupon 3, painted ceramic, 2010

Alvarez’s girls were innocent and beautiful. And we see glimpses of it—the pink sleeper and the yellow binky (El Chupon 3). But they live in an adult world—they smoke, carry guns, and glare. They are also deprived—deprived of limbs (Falling Rope of Silence), clothes, joy, and faith. These creatures trust no one, because they are not loved.

Claudia Alvarez, Donde nacio la Lluvia, 2005, oil on canvas, 83″ x 83″

In Alvarez’s ceramic sculptures, the crouching figures occupy our space, haunting us with their presence. In her paintings, the figures seem to emerge, often only partially, from an ominous atmosphere. But what is it that bothers me about these children? What is so strange about them?

Fear.

They are afraid. But not just afraid of the dark, or afraid of the bogeyman. Alvarez’s children experience the fear that characterizes adult life, that existential suffering that drains the world of its enchantment and wonder, its grace and love. We call this fear something else in the adult world—it’s determination, passion, courage, strength—a whole glossary of euphemisms that masks the terror that we live with on a daily basis. Every day is a fight—a fight for justification and recognition. We feel it. We don’t want our children to feel it, yet. And Alvarez’s children haven’t learned to hide it. It deforms them, transforms them into something other than children.

And this is what Alvarez’s children have become—something other than children. And they bother me. Again, I think of Cosette. She’s given a nickname among the villagers, the Lark. Hugo tells us why:

No larger than a bird, trembling, frightened, and shivering, first to wake every morning in the house and the village, always in the street or in the fields before dawn (p. 157).

But Hugo continues, “except that the poor lark never sang.” Cosette lurks behind the eyes of The Flower Girl.

A child is made to sing. And there is something evil about a child who cannot. A child who cannot play. Alvarez’s children are silent. And they do not play.

Her work reminds us that children are not born into Disneyland. They are often born into Newtown, into Ethiopia, into ER incubators, into crack houses—into murder, starvation, and suffering. Alvarez’s work forces me to ask, where is God in the suffering of a child? How can God create such a beautiful lark that cannot sing?

So, what does Christmas have to do with Claudia Alvarez’s children? The only answer is the one that Dr. Linebaugh offered yesterday, the same answer that Alyosha gives his older brother, Ivan, who, in Dostoyevsky’s Brothers Karamozov, demands an answer to suffering, especially the suffering of children.

Jesus.

The child who was born to suffer and die for us. The child who makes us all children through faith.

And gives us a song to sing, even in the suffering.