It’s rather serendipitous that on the same day that I was questioning my own meaning and purpose and considering whether to continue advancing my own ultimate goal, that a large package arrived in the mail. I wasn’t expecting a package. When I opened it, I found that it was filled with 40 books. The best day ever, right? My children helped me unpack the stacks of books and there was one in particular that stood out—even my daughter noticed it and said, “This looks like a cool book!”—judging the book by its cover, I couldn’t disagree with her.

The bold, sunflower yellow words Psychedelic Christianity lay bluntly on top of a picturesque depiction of what appears to be a birch tree, blossoming with new leaves in front of a red stained-glass window. I’ve never really paid much attention to the cover of a book before, but I must say, this one drew me in.

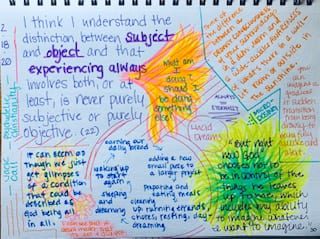

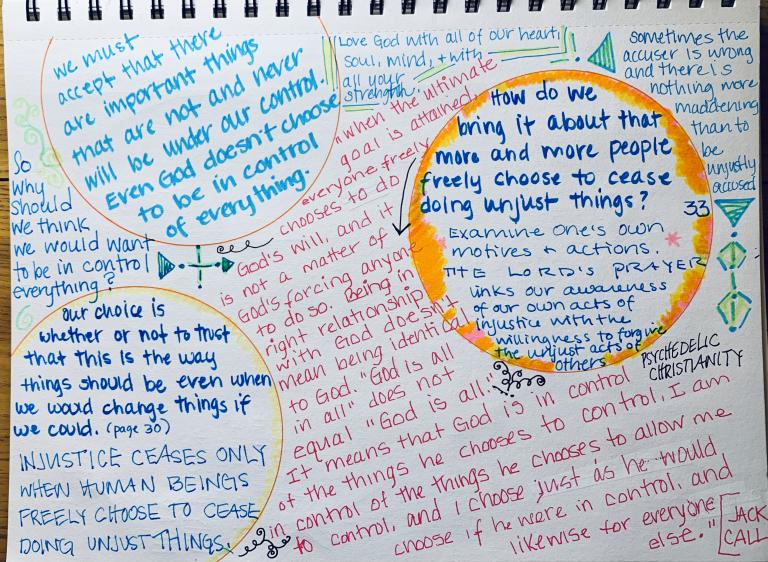

Jack Call’s writing style is cerebrally philosophical and inquisitively seductive. His way of posing question after question lured me in to consume page after page, with tantalizing enjoyment, I must add. Call is comfortable with his curious, human nature. He dared to discover deeper possibilities of the questions we all have in life. The concepts that he extrapolates from his own psychedelic experiences and recorded in ink have confounded my thoughts. Call poses bold questions and postulates riveting considerations for a new truth.

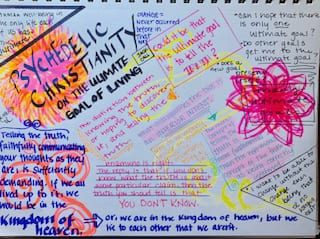

The first question asked is a big one: What’s the point? The same question I was asking myself earlier that morning before the package arrived. A question I have asked out loud several times in the last few months. More so, “what is the point, the goal, the purpose? What is it all for?” Call asks: “Is there an ultimate goal?” and while one reflects on such an extraordinary and expansive question, he follows up by asking, “Could it be that the ultimate goal is to tell the truth?”

“And you shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free,” (John 8:32) Call sees this as Jesus suggesting that being free is the ultimate goal. He notes that “Jesus talked about knowing the truth, not telling the truth.” ( 2) But how do we discern the truth? How can we know the truth if we cannot identify the truth?

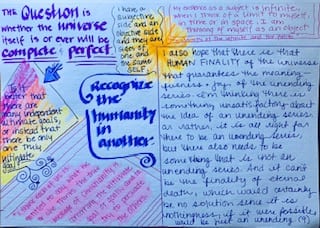

Call prefers to use the concepts of truth as distinguished by Unamuno, whereas we see truth as objective and subjective.

One is the truth that may or may not be known, that is, the objective facts about how things are. The other is the faithful correspondence between a person’s inner states or processes of believing and what he or she communicates to someone else. It is the distinction between knowing the truth, or hoping to discover it, and telling the truth. The opposite of knowing the truth is being ignorant. The opposite of telling the truth is lying. The outward evidence in both cases is the same: someone saying something false or otherwise acting as if something false is true. What distinguishes the two is an interior intent. The distinction is no great revelation, but it is often ignored when someone unfairly accuses someone else of lying who really just sincerely has a false belief and isn’t guilty of being willfully ignorant.

What stands out to me is that Call touches on a redundant scenario that I experience—one that most of us can relate to—unfair accusations of either lying or being willfully ignorant in disagreements with others. During our textual exchanges of words with others in the social media realms, we enjoy the insta-opportunity to pre-judge a person with as little information as possible. When we do this, we are typically incorrect in our assessments.

What change could we bring about if we first established a basic foundation that centers on recognizing the ultimate goal is, to tell the truth? And what if the only assumption we dared to make was that of believing the other person is intentionally truthful and substantively informed? What if instead of assuming the other person is woefully and intentionally ignorant or blatantly lying, we assumed something positive about them?

“The other is the faithful correspondence between a person’s inner states or processes of believing and what he or she communicates to someone else.”

Subjective truth is to be used in collaboration with objective truth, not to oppose it. This means that we do not allow our own subjective understanding of the objective truth to be used against another simply because we lack their unique, personal experience. We must stop impersonalizing the experience of another simply because it doesn’t resemble my own.

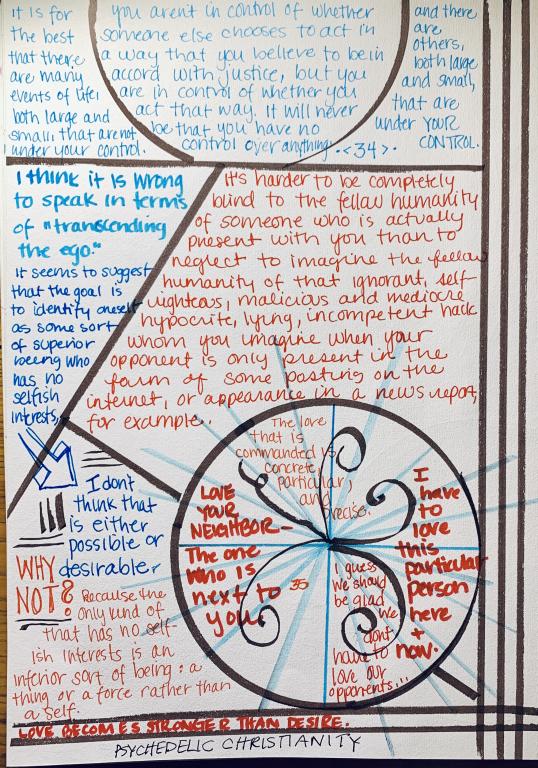

Not only have we depersonalized the other, but we have dehumanized the other. We have forgotten to see our neighbor. And perhaps when we do see the neighbor, we have too many conditions and expectations regarding who our neighbor is, that we won’t claim a neighbor.

In the Gospel of Luke, when the expert in law asks Jesus “And who is my neighbor?” (10:29), Jesus responds with the parable we all know well— the parable of the Good Samaritan. For many years, I believed that to be the foreigner, the homeless on the streets, anyone I passed by and made eye contact with. But what if it’s more intimate than that?

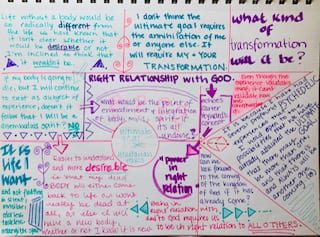

Call’s response is confounding; your neighbor is “the one who is next to you…”

Why doesn’t [Jesus] say you should love everybody no matter how near or far? I think it is because the love that is commanded is concrete, particular, and precise. It is much easier to believe that one is obeying if one thinks the love that is commanded is abstract, general, and vague, flowing out from oneself to encompass all of humanity. But Jesus is saying I have to love this particular person I happen to be interacting with here and now… (35)

The proximity and the particularity of the other constitute my neighbor. It’s how we relate to the one we are interacting with at any given time. How do we love our neighbor as ourselves? What does that include? I think Call’s Psychedelic Christianity peels back the superficiality of the neighbor—a pseudo representation that we weren’t always willing to confront because it didn’t serve our own selfish interests.

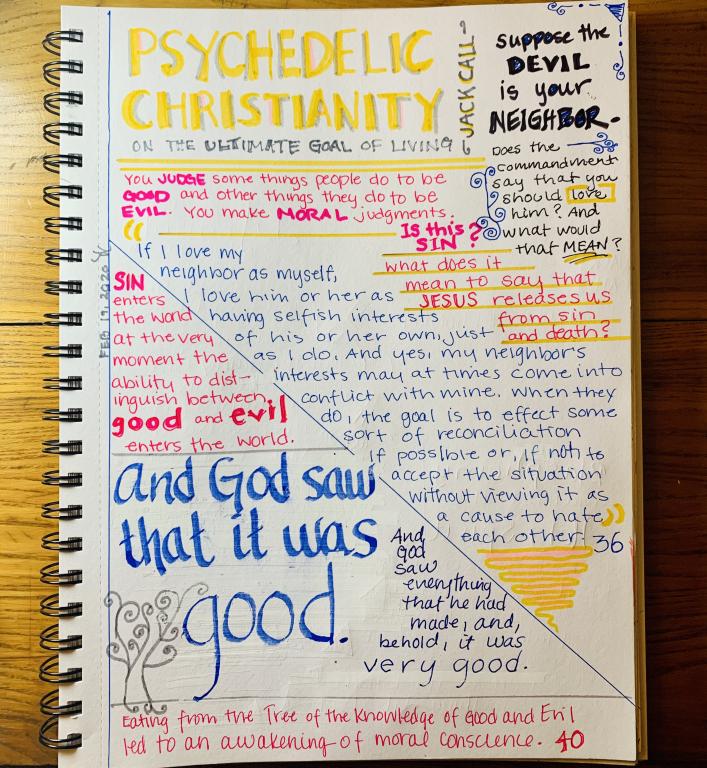

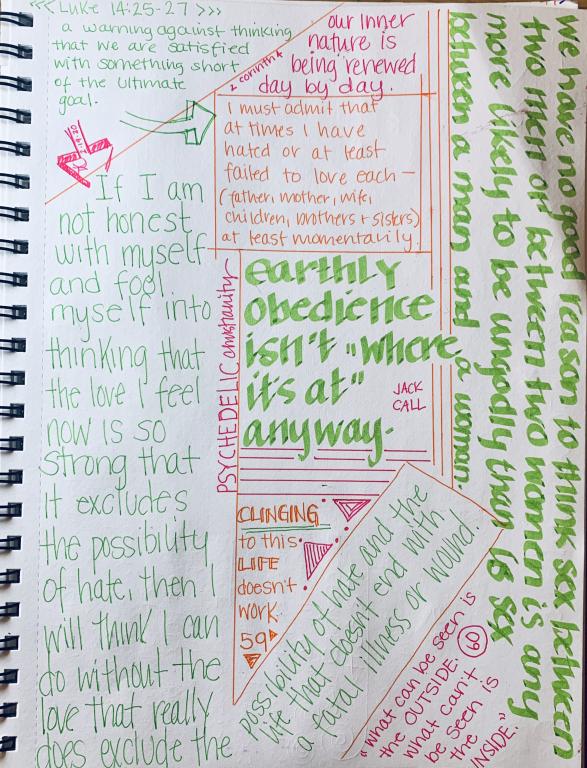

If I love my neighbor as myself, I love him or her as having selfish interests of his or her own, just as I do. And yes, my neighbor’s interests may at times come into conflict with mine. When they do, the goal is to effect some sort of reconciliation if possible or, if not, to accept the situation without viewing it as a cause to hate each other. (36)

This makes me consider the ways in which we yearn for others to simply understand our point of view, all the while remaining almost certain that the way we see things is the right way. Well, yes, but if I believe that about myself, shouldn’t I also believe that every individual I interact with also believes that for themselves? That those who oppose my view or whose views challenge my own could also see things through their eyes as the truth?

This is our neighbor: as we see them, we see ourselves, or, at least I believe we should. Right relationship with God looks like right relationship with God who is all in all, which means my neighbor.

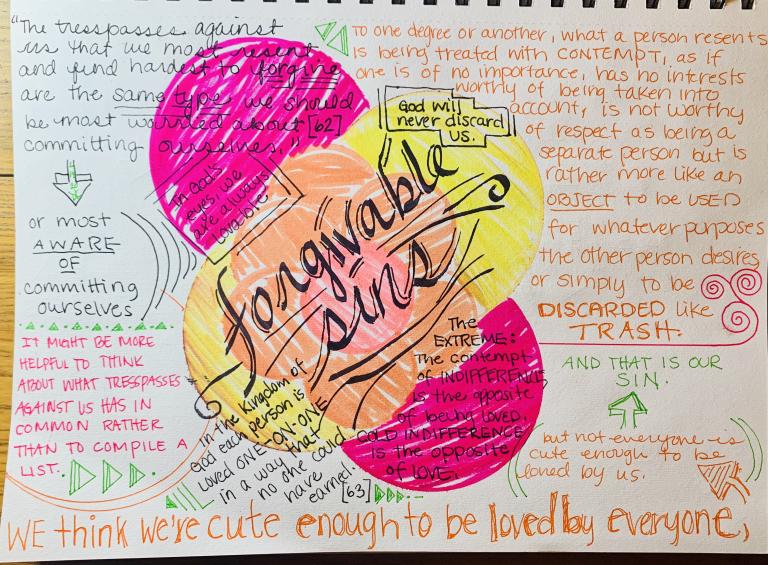

Is it easier for us to dehumanize the other that disagrees with us or our views if we see the other as “evil” and the Devil? We believe that the Devil is not our neighbor. And by association, anything deemed evil we must hate, or reject, or condescending, or attack, or assault. Why do we do this? Call says, “It’s harder to be completely blind to the fellow humanity of someone who is actually present with you than to neglect to imagine the fellow humanity of that ignorant, self-righteous, malicious and mediocre hypocrite, lying, incompetent hack whom you imagine when your opponent is only present in the form of some posting on the internet, or appearance in a news report, for example.” If we can strip away the dignity and divinity that we know we should be able to see in the other, we can justify our hatred and contempt for others. It’s terribly easy to do this when the other is behind a screen.

But “Suppose the Devil is your neighbor. Does the commandment say that you should love him? And what would that mean?” (37) Suppose your neighbor is Donald Trump or Michael Bloomberg, or Nancy Pelosi, or Alexandria Octavio-Cortez, or Michelle Obama, or John Piper, or Francis Chan. Suppose that, if we, as Call speculates, hate ourselves and we inevitably end up hating our neighbors, then when we are hating our neighbors, we end up hating ourselves. What would this mean?

It seems as if we get caught up in a cycle of hate rather than a cycle of love when we justify hating what is “evil” without clarifying, universally, that which is evil and why.

For most of us, the aforementioned people are actually not our neighbors. So, the bigger question we can ask ourselves is if she or he is not my neighbor, must I love her or him? What if we asked yet another question instead: What if I can hope for that person—who is not in my direct proximity; that they are working towards attaining a right relationship with God for their ultimate goal, and that somehow, my knowledge of that person would contribute to my own ultimate goal? What if we didn’t look for a cause to hate another, or even announce our contempt for another unless we thought that by doing so it would actively contribute to bringing the kingdom of heaven to earth?

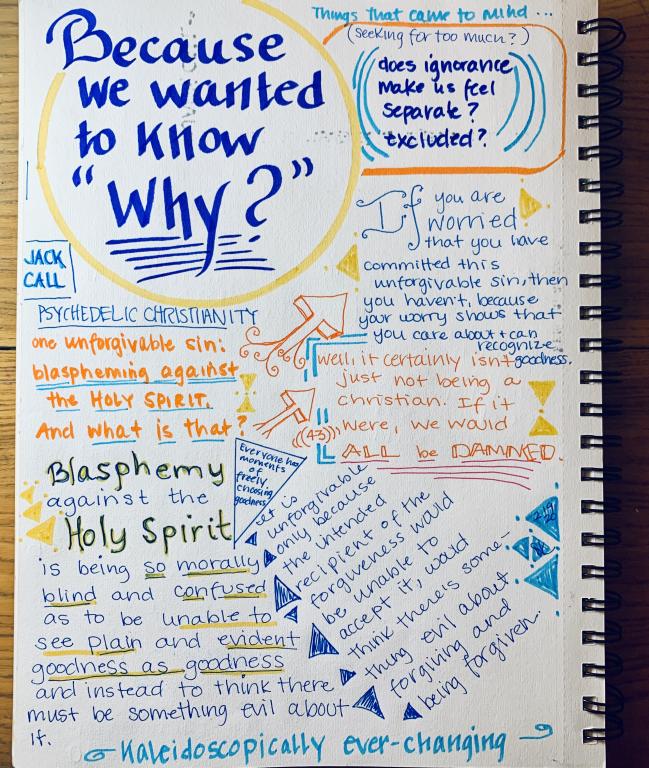

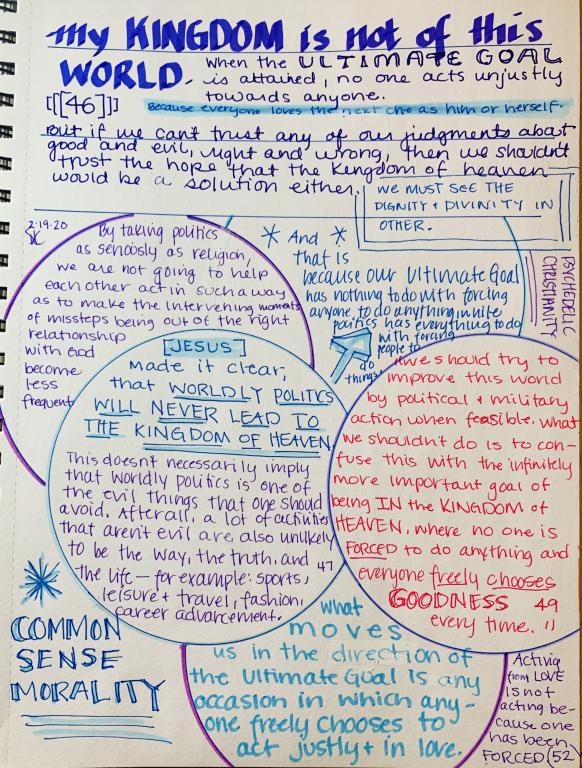

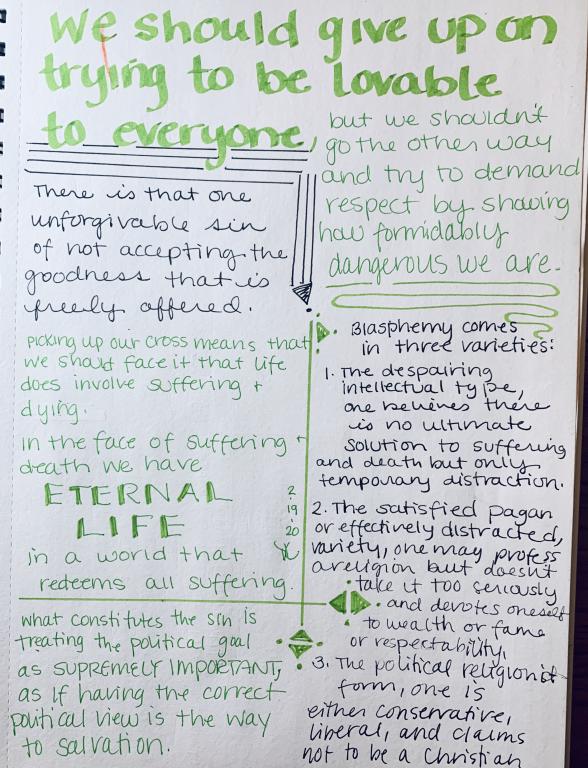

Call suspects that we can do just by acknowledging that the Kingdom is not of this world. “When the ultimate goal is attained, no one acts unjustly towards anyone.” (46) That is because realizing and pursuing the attainment of your ultimate goal includes the ability to discern goodness as goodness. Refusing to see goodness as goodness is what Call defines as the unforgivable sin. “Blasphemy against the Holy Spirit is being so morally blind and confused as to be unable to see plain and evident goodness as goodness and instead to think there must be something evil about it.” (44)

This is the sin that entered the world in the Garden of Eden. Eating from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil led to an awakening of moral conscience. God sees everything as good, behold, it was very good. For Call, the awakening of moral conscience and the point of the story is, as he sees it, “That sin enters the world at the very moment the ability to distinguish between good and evil enters the world.” (39) As soon as Eve and Adam were able to discern good from evil, they could delude themselves for having realized they made a mistake, by letting their desires guide them. They could manipulate their own self- image and effectively find cause to hate themselves or each other. They could have freely chosen God’s will at that moment and remained in right relationship to God, but instead, sought after more, followed their desire, and ever since then, we have been trying to undo the original sin.

Justice has been the worldly way of conquering sin. And we enact righteous justice by way of politics in the United States. Since the dawn of the Republic, society has advanced to bring about progress through extending rights and observing injustice and thwarting it. But one thing that Call wants to emphasize, is that Jesus “made it clear that worldly politics will never lead to the kingdom of heaven.” (46) It’s not that Call believes politics is “one of the evil things that one should avoid.” He admits, many activities are not “necessarily evil” but “are also unlikely to be the way, the truth, and the life—for example: sports, leisure and travel, fashion, career advancement.” (47)

For me, this means that not everything we do is in God’s will, nor advances our ultimate goal, nor does it mean that it brings the kingdom of God to earth. Some things we do just to fill space and time (and our present moments of uniting the now with the kingdom of God transcend space and time).

Call is quite blunt.

The goal of politics is to create policies about how we live our lives together, where those policies are enforced by a system of rewards and punishments, with an emphasis on the latter…I think the more we treat politics like a sport and the less we treat it like a religion, the better off we are…And that is because our ultimate goal has nothing to do with forcing anyone to do anything, while politics has everything to do with forcing people to do things. (47-48)

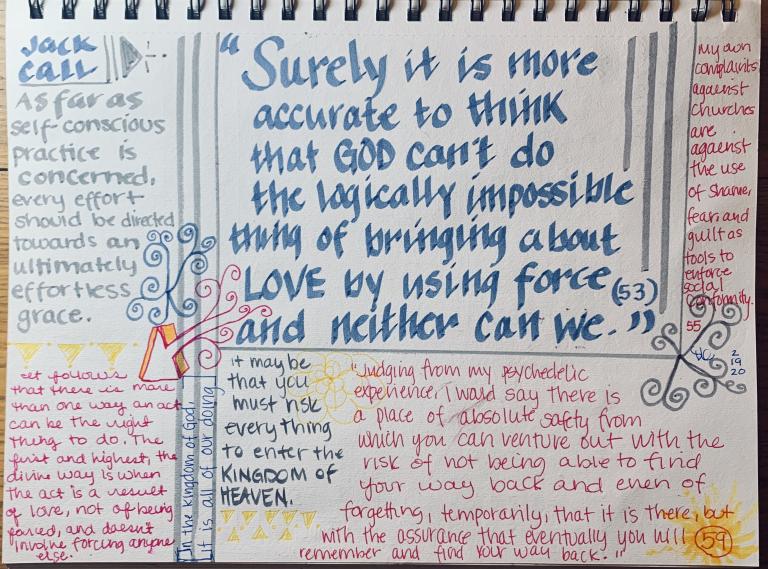

The Kingdom of God is not about control or force, or votes and propaganda, or comparison and competition. None of us has the power to force another to act unjustly. But we do have the power to cease to act unjustly ourselves. “The kingdom of God happens when everyone exercises this capacity and loves God and neighbor so that everyone freely chooses always to do what is just as the natural consequence of that love.” (52) Call does not suggest that we do nothing, just that we don’t force anything that would create greater harm that the initial intervention of protection.

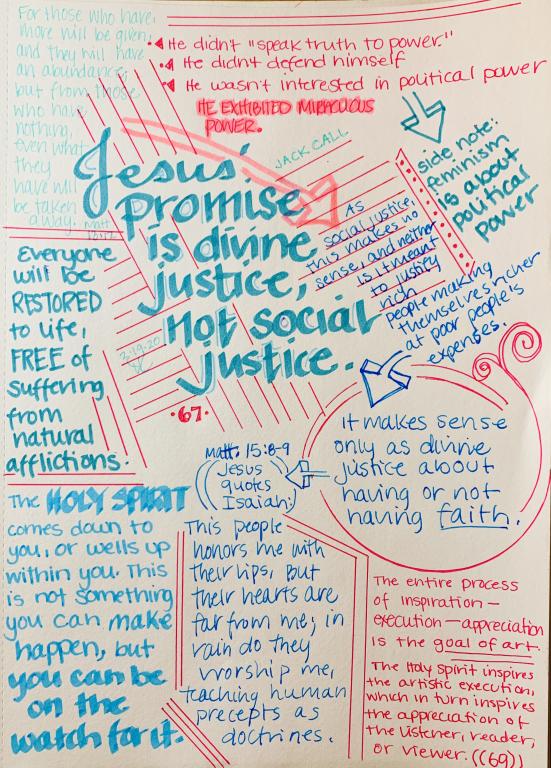

Psychedelic Christianity presents another climatic and provocative statement that demands maximum absorption; “Jesus’ promise is divine justice, not social justice.” (67)

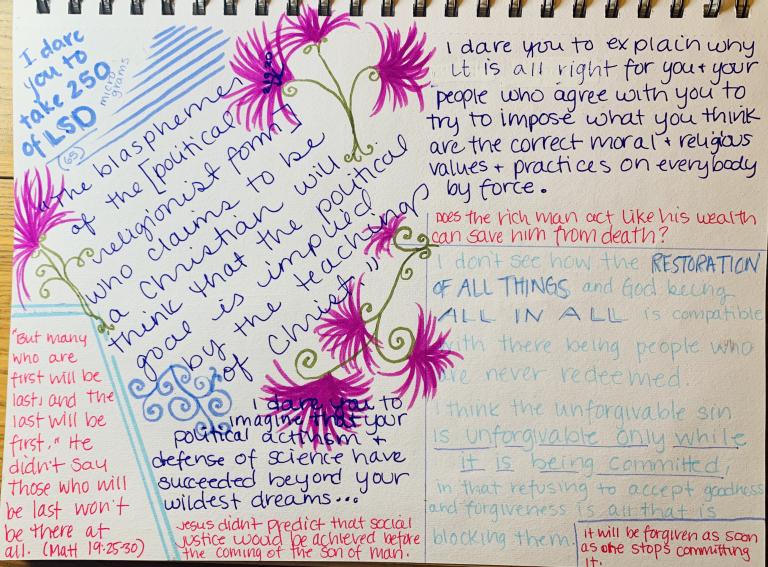

A profound yet paralyzing concept that he unpacks ardently, selecting Matthew 13:12 for readers to consider. For those who have, more will be given, and they will have abundance; but for those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away. Call notes, “As social justice, this makes no sense, and neither is it meant to justify rich people making themselves richer at poor people’s expenses. It makes sense only as divine justice about having or not having faith.” Call observes that Jesus didn’t “speak truth to power, he didn’t defend himself, and he wasn’t interested in political power. But “he exhibited miraculous power.”

Politics that look like religion are not religion. Politics are not meant to bring about the kingdom of heaven. And as an aside, I came to a deeper understanding of why feminism’s fundamental roots rub so coarsely against the tubers of Christianity’s modesty movement. Both represent a desire for a political power that is not necessary in the Kingdom. Feminism aims for political power equal to (and sometimes more than) a man, while the modesty movement and its associations of purity and virginity culture prefer the patriarchal politics of male power over females as sacred and holy property to be owned. Either way you look at it, both ways depend on the comparison or ruling of man, and not God. Neither will bring about the kingdom of God nor lead us to attaining the ultimate goal.

Politics are naturally divisive. Jesus was naturally inclusive. Jesus did say “But many who are first will be last, and the last will be first.” “He didn’t say those who will be last won’t be there at all.” Current political rhetoric permits the cruelest and most vulgar methods of dehumanizing the opposing side. People are targeted and excluded solely because of who they vote for. But if politics won’t advance the kingdom of God,

Does Psychedelic Christianity entice me to consider hallucinogens? Not currently. I do, however, believe that I am near the same frequency of understanding how Jack Call can see life as he does. The ultimate goal can bring us peace and contentment and we don’t have to dare ourselves to take 250 micrograms of LSD to attain it.

The ultimate goal is simple yet complex and perhaps that is why for many, it takes complex compounds to see what the ultimate goal is. Call’s psychedelic experiences allowed him to strip away the false pretenses of the reality that has been built around us to reveal something more transcendent and readily available. He doesn’t intend that others discover such a goal the same way he does, but he does dare you to. A dare that I would like to accept in the future.

* Jack Call is Janitor and President of the Institute for the Advancement of Psychedelic Christianity. He taught philosophy at Citrus College in Glendora, California for 19 years. He has published numerous essays on the relations between philosophy, religion and social science and is the author of God is a Symbol of Something True and Dreams and Resurrection.

You can purchase Psychedelic Christianity: On the Ultimate Goal of Living here.

The TL; DR Version: