(From Wikimedia Commons)

1.

Why did Jesus need to travel through Samaria in order to reach the Galilee from Judea (4:4)? If, as I’ve been saying, he was baptizing at the Jordan River somewhere not too far from Jericho and the northern end of the Dead Sea, couldn’t he simply have traveled northward up the Jordan Valley, and reached Galilee (or, more specifically, the Sea of Galilee) that way? Why did he need to climb up to the hilly country of Palestine’s central mountain range and then travel up and down and up and down through the hills of Samaria? Why didn’t he avoid Samaria, as Jews of his time commonly did (4:9)?

My answer: Because he didn’t care about avoiding Samaritans. And, of course, because he was apparently going to Nazareth, which is up in the central hills, before he went down via Cana to Capernaum, which is on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. (See Matthew 4:12; Mark 1:21; Luke 4:31; John 2:12, 4:46.)

2.

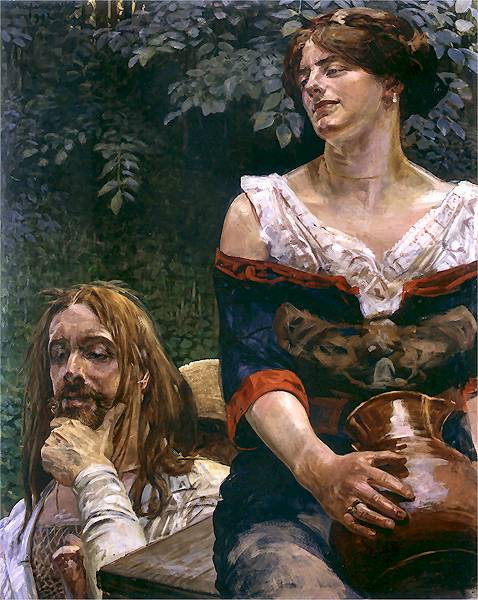

When John 4:6 notes that “it was about the sixth hour,” that means that it was roughly six hours after sunrise. In other words, it was about high noon, and probably pretty hot. That helps to explain why Jesus was “weary,” and why he sat down by the well. This Polish painting is strikingly modern, but the scene is quite a bit too green, leafy, and cool:

(Jacek Malczewski, d. 1929)

From Wikimedia Commons

3.

I’ve always been amused by the portion of the story of the woman at the well in which, Jesus having indicated that he knows about her apparently-not-quite-married state, she abruptly changes the topic by raising the question of Jewish/Samaritan disagreements concerning where God should be worshiped (4:16-20). But she’s plainly very impressed by his unexpected and miraculous knowledge of her (“Sir, I perceive that you are a prophet”), just as Nathaniel had been, earlier (John 1:47-50).

4.

Most Latter-day Saint missionaries, I would guess, have been confronted with John 4:24 (“God is a Spirit) as part of an argument against Mormonism’s concept of God as embodied. I’ve always found this argument misguided. It would have been very odd if, in a dispute about how and where to worship God, Jesus had suddenly let forth an irrelevant comment about the ontological character of God. He’s saying, rather, that God is spiritual, and that worship must be spiritual, too. But, in that sense, we too are spiritual. God isn’t simply a rock. Nor are we, although — like God — we’re enclosed in flesh. Worship is a spiritual matter, not just one of outward observances and particular geographical locations.

The Greek of John 4:24 reads πνεῦμα ὁ θεός, and it can be argued — I would argue — that the King James Bible’s indefinite article a (“God is a spirit”) misleads readers just a bit. The 1545 Luther Bible handles this passage better, in my judgment, when it omits the indefinite article (“Gott ist Geist,” in other words, rather than “Gott ist ein Geist”), as do such modern English translations as the English Standard Version and the rendering by J. B. Phillips, both of which have “God is spirit.”

5.

I’m struck by the contrast between Nicodemus, the “ruler of the Jews” who’s mentioned in John 3, and this ordinary Samaritan woman. The honorable Nicodemus comes to Jesus by night, apparently doesn’t understand what Jesus tells him, describes Jesus merely as “a teacher sent from God,” and, so far as we can see from that chapter, tells nobody else about his conversation with the Savior. The morally slightly ambiguous Samaritan woman at the well, by contrast, converses with Jesus in broad daylight, perhaps even at high noon, immediately perceives him to be a prophet, and tells everybody in her village about him, wondering if he could perhaps be the Messiah. Soon, they’re all declaring that he is “indeed the Savior of the world” (4:42).

There’s so much more that might be said about this encounter, but I’ll leave it at that.