Our (superb) guide on the recent Interpreter Foundation Church history tour, Peter Fagg — whom my wife and I have known for years now, and who will also, if all goes according to plan, accompany us on a Christian history-themed tour of England in May of 2026 — shared these remarks with us while we were there a few weeks ago. We liked them so very much that we invited him to share them with the readership of the Interpreter Foundation. He generously agreed to do so: “Empty Chairs: Reflections on How Faithful Latter-day Saints Can Handle the Pain Presented by Wayward Loved Ones,” written by Peter Fagg

[Editor’s Note: Peter Fagg gave these remarks at a Sacrament Meeting of the Chorley Second Ward of the Preston England Stake on 30 June 2024. With his kind permission, we share them here, lightly edited, with the hope that they might be helpful and comforting to some of our readers.]

We held our quarterly Interpreter Foundation board meeting today. I’m deeply impressed by — and very grateful for — all of the time and effort that our uncompensated board puts into the Foundation’s work, along with the time and effort given by all of our volunteers. Jeff Bradshaw returned only very early this morning from (I think) six weeks in Africa, where he’s been working on the Not by Bread Alone project.

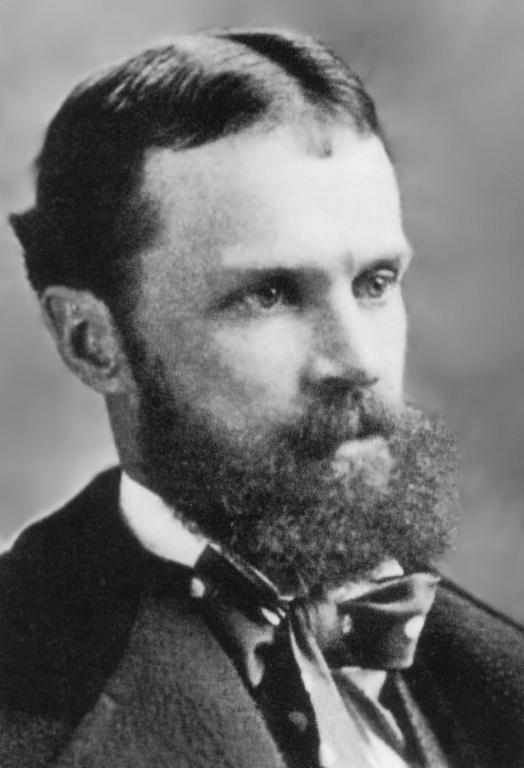

I want to share some passages that I recently marked during a reading of Deborah Blum, Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death (Penguin, 2007):

James and his companions in this scientific ghost hunt were famed for their intellectual brilliance—their intellectual courage gained them less admiration. Yet they possessed both qualities in abundance. James’s fellow ghost hunters included the codiscoverer of the theory of evolution, a physiologist from France who would win the Nobel Prize in Medicine, an Australian who became a founding member of the American Anthropological Society, a female mathematician who became principal of Cambridge University’s first college for women, a pioneer in British utilitarian philosophy, and a trio of respected physicists. All of them had reputations that would suffer as a consequence, and all of them, like William James, would refuse to abandon the search. (15)James wrote to Science magazine, a journal devoted to upholding the research ethic, that he loathed the reverential use of the word “scientist … it suggests to me the priggish, sectarian view of science, as something against religion, against sentiment,” even against real-life experience. (17)

In his most famous demonstration—investigated by German philosopher Immanuel Kant—Swedenborg disrupted a garden party by suddenly announcing a firestorm in Stockholm, some three hundred miles away. Staring at a clear evening sky, Swedenborg described the fire’s progress, street by street and building by building, to the disbelieving company. Two days later, a messenger from Stockholm confirmed every detail. Kant concluded that the case showed “beyond all possibility of doubt” that Swedenborg did indeed possess an extraordinary visionary gift. (23)

“The ideal of every science is that of a closed and completed system of truth,” James acknowledged. If supernatural events did not match the categories of the scientific system they “must be held untrue.” James admired the efficiency of the “scientific” approach to the spiritual murkiness. “It is far better tactics, if you wish to get rid of mystery, to brand the narratives themselves as unworthy of trust,” James wrote. But while he agreed that most so-called supernatural events were suspect, he worried that scientists stayed deliberately blind to the rare credible ones, that researchers might be ignoring “a natural kind of fact of which we do not yet know the full extent.” And he worried too about the larger effect of such prejudice on the way people viewed science itself. “Thousands of sensitive organizations in the United States today live as steadily in the light of these experiences, and are as indifferent to modern science, as if they lived in Bohemia in the twelfth century. They are indifferent to science, because science is so callously indifferent to their experiences.” (42)

If scientists did not afford some respect to the beliefs of the lay public, James warned, there was little reason for the public to respect the pronouncements of science. (42)

Nations, James said simply, are not saved by wars. They are saved, he said, by “acts without external picturesqueness; by speaking, writing, voting reasonably; by smiting corruption swiftly; by good temper between parties—by people knowing true men when they see them, preferring them as leaders to rabid partisans and empty quacks.”

Finally, lest the zealous defenders of humanity against the ravages of theism grow too complacent, I offer several appalling items of evidence, drawn from the venerable Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File™, of how busybody religious believers continue to afflict and torment innocent men, women, and children around the world:

- “Church Donation Funds the Training of Breast Cancer Specialists in Mexico”

- “Church Donates Equipment to Koforidua Polyclinic in Ghana”

- “The Church Gifts Ethiopian Christians a New Worship Space in Utah.” “If everyone followed the example of your prophets and saw things from a wider perspective, we wouldn’t have this worrisome world.”

- “A Closer Look at Caring: How the Church Is Helping in Jordan, Cambodia and Mongolia”