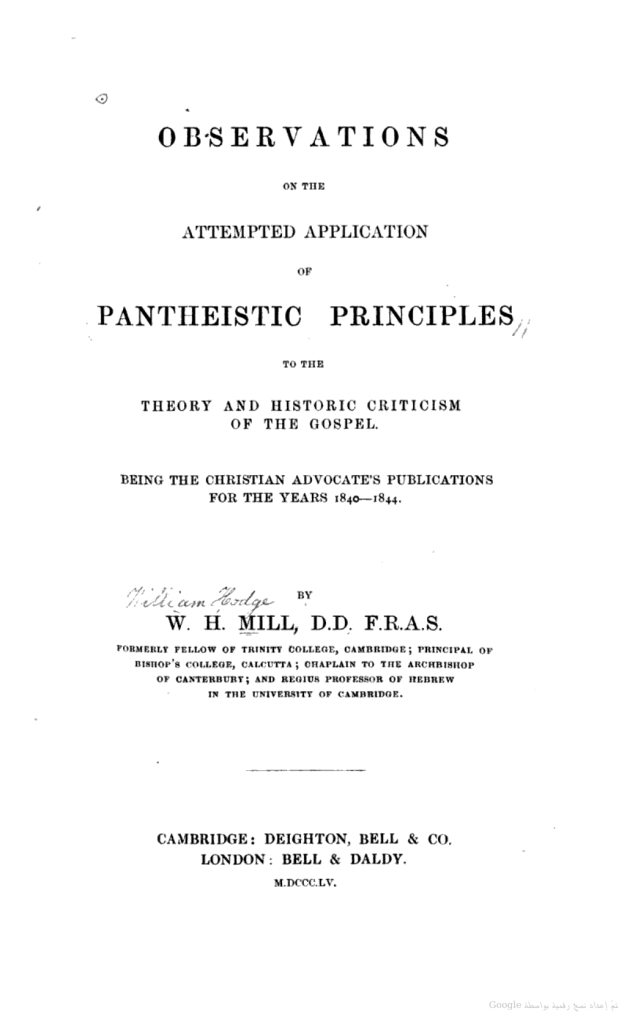

William Hodge Mill (1792–1853) was an English Anglican priest, orientalist, and professor of Hebrew at Cambridge, with a canonry at Ely Cathedral. The following is drawn from the chapter, “The Record of the Brotherhood of Jesus in the Gospels” (pp. 221-316) in his book, Observations on the Attempted Application of Pantheistic Principles to the Theory and Historic Criticism of the Gospel (Cambridge: Deighton, Bell & Co. / London: Bell & Daldy, 1855). It’s considered one of the classic treatment of the “cousins” theory of Jesus’ so-called “brothers” (famously set forth by St. Jerome and largely followed by the western Catholic Church and the first Protestant leaders). This theory is consistent with a belief in the perpetual virginity of Mary.

The Catholic Encyclopedia, “The Brethren of the Lord” (Florentine Bechtel, 1907), recommends it as one of eight sources regarding Jerome’s theory. For the step-brother, or “Epiphanian” theory (the “brothers” were children of Joseph from a previous marriage, favored by the Orthodox and Eastern Catholics), this article recommends one source: St. Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians (Andover: Warren F. Draper, 1870), by the renowned Anglican theologian and commentator, Bishop J. B. Lightfoot (1828-1889); specifically, its section, “The Brethren of the Lord” (pp. 88-128). Lightfoot himself in this volume thought that Mill’s treatment was among the “most important” on the topic, and stated that “I am also largely indebted to the ability and learning of Mill’s treatise”.

I won’t bother with page numbers, since anyone who wishes to do so can search any words by consulting the online Google Books version that I am utilizing. Paragraph breaks will be indicated by a space; omissions of portions of the text, by ellipses (. . .) only, or ellipses immediately followed by a space. Footnotes will be in brackets ([ ]) and blue color.

*****

The subject of our Lord’s genealogical descent is intimately connected with that of the persons whom all the four Evangelists term his brethren: on whose actual relation to Mary and to Joseph I would now propose some observations. Though a question not altogether without obscurity, I hope to show that the difficulties are by no means so inextricable, as Strauss, with even more than his usual desire of entanglement, has laboured to represent them: . . .

Of the notices of these singularly favoured persons in the New Testament, the most complete is that in the Gospels of St Matthew and St Mark,- where the people of Nazareth, the earliest and the nearest witnesses of all that concerned the immediate family of our Lord, exclaim, on first hearing his public announcement of himself in their synagogue, “Whence hath this man this wisdom and these mighty works? Is not this the carpenter’s son? Is not his mother called Mary (Mariam)? and his brethren James (Jacob) and Joses and Simon and Judas? And his sisters, are they not all with us? Whence then hath this man all these things?” [Mt 13:54-56; (cf.) Mk 6:2-3] . . .

The same two Gospels which, in the speech of the Nazarenes, give us the names of James and Joses, with Simon and Judas, as brethren of Jesus,- tell us also that among the pious women who witnessed the crucifixion, having accompanied our Lord from Galilee, were Salome the wife of Zebedee, Mary of Magdala, and Mary the mother of James and Joses; that these two last, viz. “Mary Magdalene and the other Mary” carefully marked on that sad evening, the spot of burial, and all the three approached the holy sepulchre with ointments on the Easter morn.

These are St Matthew’s expressions respecting this new Mary; St Mark, when relating the same things, using in the first instance, the phrase “Mary the mother of James the Less (‘Ιακώβου τοῦ μικροῦ) and Joses, to distinguish the former from James the Great the son of Zebedee and Salome; and in the two last instances, instead “of the other Mary,” calling her severally, the mother of Joses (Μαρία ᾿Ιωσῆ), and the mother of James (Μαρία ἡ τοῦ ᾿Ιακώβου). And who was this ” other Mary,” the companion of Mary Magdalene at Calvary, we learn distinctly from one who was there present with them; and who also tells us, that not content with beholding from afar the scene of suffering, these same two Maries, towards the close, were with the afflicted mother herself, and the writer, at the foot of the Cross.

From St John, the witness alluded to, we learn that the Mary in question was the sister of that most honoured person whom she then accompanied, and whose name she bore; and that she was either the wife (as it is most generally understood), or else the daughter, of Clopas; ἡ τοῦ Κλωπᾶ. Lastly, she is associated with Mary Magdalene after the resurrection, by St Luke also; by whom, as by St Mark, she is called “the mother of James” (Μαρία Ιακώβου). Proceeding therefore on the principle already mentioned with respect to this last distinguished name, have we not here the amplest proof that we could desire, from the testimony of all the Gospels taken together [See Matt. xxvii. 56, 61. xxviii. 16. comparing the three places respectively with Mark xv. 40, 47. xvi. 1: comparing also John xix. 25. with the first place of each of the two series, and Luke xxiv. 10. with the last.], that the mother of St James the Just and his brother Joses was not the blessed Virgin Mary, but her sister of the same name?

The domiciliation of either sister, when a widow, in the other’s house at Nazareth, on the decease of Joseph or of Clopas, so that the children of both would thenceforth form but one household, is therefore a most conceivable and probable event; still more if, as the ancient Judæo-Christian historian, Hegesippus, positively testifies, those husbands of the sisters were themselves brothers [. . . The marriage of two brothers to two sisters appears to have been no uncommon case among the Hebrews. . . . Nor is the circumstance of the two Maries bearing the same name, destructive of the notion of even their strictest sisterhood: of which the family of the Herods, abounding with cognominal brothers, is sufficient proof.].

The occasion for the mention of this is supplied to the historian by Simon or Symeon (שמעון) the son of Clopas, who on the martyrdom of St James the Just became the second Bishop of Jerusalem, being, like him, a cousin of our Lord, his father being “mentioned in the Gospel,” (viz. in John xix. 25). Now even if Symeon were a son of Clopas by a former wife, and this were likewise the case with his yet more eminent brother Jude, they were still sufficiently near to Jesus to be termed brethren in Matt. xiii. 55, and Mark vi. 3: while James and Joses, the declared children of Mary the wife of Clopas and sister of our Lord’s mother, would stand in the most intimate natural relation to Him.

The conclusion to which a positive testimony has thus conducted us would have been reached, as far as the negation of strict brotherhood is concerned, by two independent lines of argument, equally irrefragable, from Scripture. 1. We have seen St Paul’s testimony to our Lord’s brother, St James, as an Apostle, and a pillar among Apostles co-ordinately with St Peter and St John; which could not be, unless he were either of the original Apostolic College, or else extraordinarily called, as we read of St Paul alone, by the same Lord that chose the twelve, to a footing of equality with them: and if any thing were wanting to the proof of this fact, we should have it in the authoritative decision pronounced by him in the Apostolical Council at Jerusalem.

Now in the list of the chosen Apostles, as given severally by St Matthew, St Mark, and St Luke, we read after St James Boanerges the son of Zebedee, but one other James, viz. James the son of Alphœus: whose name is in the last-named sacred historian’s list, followed by Simon Zelotes, and Judas the brother of James: but in the two other Gospels, by the names of the same Apostles rather differently exhibited, without reference to the relationship, and in an inverted order, viz. Lebbæus or Thaddæus and Simon Cananites. Now we may lay it down as certain, that he whom St Matthew and St Luke call the son of Alphæus cannot be the son of Joseph, of whom their opening chapters are full: the notion of our Lord’s brother being such, and still more, that of his being the son of Joseph and Mary, is therefore at once refuted.

But is there any obstacle to his being accounted (what this argument compels us to esteem him) the son of the blessed Virgin’s sister Mary? Certainly none; if either we conceive Alphæus and Clopas to have been successive husbands of this Mary, – or one the husband, the other the father-or, what is more probable, both the same husband: ᾿Αλφαῖος and Κλωπᾶς being indeed not so much as different names of that person, but only different ways (both agreeable to ordinary usage) of representing in European letters one and the same Aramean name אָזְלַח . . . [That Alphœus and Clopas should be Hellenic exhibitions of one and the same Syriac name, is not more strange than that in the far less dissimilar languages of Southern and Northern Europe, Aloysius and Ludovicus should be both recognized Latin representatives of the same Franco- Teutonic name Louis or Ludwig. This name, in the founder of the Frankish monarchy, is written Clodoveus or Clovis: in succeeding ages of that monarchy the hard aspiration of the initial Gothic letter was more mildly represented by the guttural Chlodovicus, then by Hludovicus or Hlouis, till even the aspirate was dropped, and in Spain and Italy the first-named depravation of the name was adopted; the two extremes, Clovis and Aloysius, bearing a certain inexact analogy to our Clopas [and] Alphœus.]

For it is to be observed that the form Clopas is peculiar to St John [It may be thought that this assertion is incorrect, because St Luke has in one place (xxiv. 18) the name Cleopas, though attached to a different person, viz. one of the two disciples whom the risen Lord joined on the walk to Emmaus: and therefore he at least would not exhibit the same name belonging to the Virgin’s brother-in-law in so different a form as Alphœus, but express it as St John does. But this is a mistake arising from the confusion of two totally different names. That disciple’s name Κλεόπας is a Hellenistic one, contracted from Κλεόπατρος after the manner of the Judæo-Alexandrine dialect, in the same manner as Αντίπας from Αντίπατρος, Καρποκρᾶς from Καρποκράτης &c.; . . . The NT and the oldest Greek fathers, as we have seen in the citations from Eusebius and Epiphanius, never confound these two names; though our version has followed the Vulgate (and the Coptic) in so doing, i. e. in calling the husband of the Mary in Joh. xix. 26, Cleopas. This distinction of the two names, as well as the identity of Κλωπᾶς and Αλφαῖος, is allowed by Blom, p. 63, though he is far from admitting our conclusion.], who on the other hand never uses the form employed by the three other evangelists to denote this and perhaps one other person of the same name [Namely, the father of Levi the publican in Mark ii. 14, in other words, of St Matthew; whose identity with Levi appears from comparing his account of his own conversion, Matt. ix. 9 seq. with the above place of St Mark, and Luke v. 27 seq.- Several Fathers, as Chrysostom, (Hom. xxxiii. in Matth. it. Cal. Græc. Oct. 9.) consider this Alphæus to be the same as the other, and consequently make St Matthew and St James the Less brothers.].

This identification, to which the collation of the sacred text has conducted the critics of these later ages, was not unknown as a matter of tradition to the earliest. We find, in a fragment bearing (and in the opinion of good judges truly bearing) the name of Papias of Hierapolis, a disciple of Apostles and of apostolic men [. . . Though we have here some incongruities, and the singularity of finding in Salome both a third Mary, and also a sister of the Virgin, (an opinion which a recent Gottingen professor has revived), yet even the rumours recorded by so very ancient an author deserve notice: and the proof is at all events complete, that the identification of Maria Clopae with the wife of Alphæus, is far older than the time of St Jerome. . . .], that “Mary the wife of Cleophas or Alphæus was the mother of James Bishop and Apostle, and of Symon and Thaddeus (or Jude) and a certain Joseph” (i.e. Joses; distinguishing by this kind of mention the only one of the four who was not celebrated in subsequent Christian history): also that ” James and Jude and Joseph (or Joses) were the sons of the maternal aunt of the Lord;”–and again stating that “Mary the mother of James the Less and wife of Alphæus was the sister of Mary the Lord’s mother:” a doubt being appended here whether St John calling her ἡ τοῦ Κλωπᾶ may not have intended to denote her father or kindred, or another husband: for the identity of the names in Syriac would not approve itself by its own evidence to the Phrygian bishop.

But whatever doubt might occur as to the identity of this secondary name, as first indicated by Papias, the identity of the son of Alphæus with the brother of our Lord is laid down by him without the least question or ambiguity. So is it also in the book on the Twelve Apostles ascribed to St Hippolytus, where the known history of the martyrdom of the first Bishop of Jerusalem, our Lord’s brother, is predicated distinctly of James the son of Alphæus. And a still older and more eminent Father, St Clement of Alexandria, states clearly and precisely that there were but two distinguished persons in the apostolical history who bore this name of James; the one, he who having been with St John his own brother and with St Peter, honoured with peculiar distinction by his Lord, was at last beheaded (by Herod Agrippa); the other the one surnamed the Just, who having been by the three preceding apostles made bishop of Jerusalem, ended his life by being precipitated from the temple, and then dispatched by a fuller’s club; the same whom St Paul saw alone of the Apostles in the holy city, and called the Lord’s brothers.

Thus does this learned Father exclude absolutely from the number of Apostles any other James than the son of Zebedee on the one hand, and our Lord’s brother, the first bishop of Jerusalem, on the other, who is therefore the son of Alphæus. These testimonies suffice to show that the view defended by St Jerome against Helvidius, and which from his time has been the generally received opinion of the Western Church, was no novel introduction of his own; and when he confidently appeals to Ignatius, Polycarp, Irenæus, Justin Martyr, and many other Apostolical men, as having refuted the ancient heretics on that point which alone Helvidius held in common with them, viz. the existence of other sons of Mary, it is not unreasonable to presume that as to the actual parentage of the alleged sons, their sentiments were not opposed to those of Clement and himself.

But beside this proof from the strictly apostolic character of our Lord’s brother, that he could not be the son of Mary or of Joseph, there is a further most powerful argument against the existence of any son of Mary beside One. In his last agony on the Cross, He commits the domestic charge of the desolate mother to the specially beloved disciple St John. Is it then credible, that in giving the last and highest sanction of Incarnate Deity to the sacredness and tenderness of the filial relation, He would make that transfer of its obligation which the words, “Woman, behold thy son,” imply, had that mother sons living, and among them a St Jude and a St James?

What are we to think, in reference to these, of the argument, that the Saviour sought less to provide the support of natural duty than of Christian sympathy to the afflicted mother, and that this last could not be imparted by the brethren, who, as yet, “believed not on him,”–when not only is the speaker one to whom even the distant future was then present, but the persons so strangely vilified by this argument were confessedly within fifty days from this time, in the upper chamber of Jerusalem, engaged in prayer and supplication with St Mary and with the Apostles, in the midst of their virulent and triumphant enemies, (πάντες προσκαρτεροῦντες ὁμοθυμαδὸν τῇ προσευχῇ καὶ τῇ δεήσει)?

It is not wonderful that they whose singular zeal to give a family of children to the blessed Virgin has compelled them to employ an argument like the foregoing, should be forced, in pursuance of it, to imagine (against all the analogies of Scripture) that our Lord’s special appearance to James [1 Cor. xv. 7, 8. Ἔπειτα ὤφθη Ἰακώβῳ · εἶτα τοῖς ἀποστόλοις πᾶσιν· ἔσχατον δὲ πάντων, ὡσπερεὶ τῷ ἐκτρώματι, ὤφθη κάμοί. It need scarcely be remarked, how strongly this passage also speaks to the fact of the St James here meant being, in the strictest sense, an Apostle: nor how the distinction drawn in the subsequent verses by St Paul, of his own case as a witness of the resurrection, and as an Apostle, from all others, makes it utterly incredible that either St James was an extraordinary Apostle like him, (though Eusebius has made a remark tending to this, . . . or that this apparition to St James should have been the means of converting him from infidelity, (an infidelity after long sight and converse with Jesus as a brother, how unlike that of Saul!)–or that it should have been at all different in kind from the apparitions mentioned in the verses preceding, viz. to Cephas, to the twelve at Jerusalem, and to the five hundred brethren in Galilee. . . . ] after the resurrection was the means of at last converting him from absolute infidelity; . . .

On every side, then, we find our Scriptural proof confirmed; that he who was constantly termed, by way of distinction, our Lord’s brother, and was assigned a post so different from all the other Apostles, yet so eminent among them, as that of fixed resident Bishop at Jerusalem, was an Apostle notwithstanding from the first, and could not have been the son of Mary. How otherwise, in a situation that so peculiarly fitted him for the office of her guardian, was he deprived of that honour and happiness, and the parent that had reared him from infancy committed to the charge of an errant Apostle?

But having arrived at so much of definite conclusion on this subject, it is well that we should enumerate some of the difficulties with which it is attended. For beside that it is never expedient to conceal from ourselves the existence of such difficulties, . . .

I. Since of the four brethren enumerated by the men of Nazareth, James and Jude his brother are proved to be of the twelve Apostles, and Simon, who certainly succeeded the former at Jerusalem, has been by many not improbably thought identical with Simon Zelotes of the same number, a difficulty follows as to the narrative in John vii., which is certainly posterior to the calling of the twelve: inasmuch as we have left but one brother, viz. Joses, to whom that narrative can possibly apply; though it is said of many, or rather of the whole number, that “neither did his brethren believe on him.”

To meet this difficulty, we may observe, (1) that it is by no means necessary to suppose all who might be according to Jewish usage termed our Lord’s brethren, to have been enumerated by the Nazarenes by name. ( 2) Neither is it necessary that all of these should have manifested that unbelief (which is not of the worst kind or degree, though incompatible with the character of a true disciple”), but only a considerable proportion of them. (3) Neither is it necessary to exclude from the unbelievers on that occasion him whom Hegesippus calls Symeon the son of Clopas: for neither in that most ancient account of him do we find any assertion or hint that he was an Apostle: nor in the enumeration of the Twelve in the Gospels is there any such family designation attached to Simon the Canaanite or Zealot, as we find attached to Jude by the third Evangelist.

(4) Neither is there any repugnancy between the history of John vii., even if conceived to relate to Simon and Joses only, and the other statements of the New Testament: for there was ample time between that feast of Tabernacles and the Passover of the year following, for the conversion of the former, and the latter also, to the better mind of their apostolic brothers. (5) Still less is there any repugnancy, if, to Joses and Simon, or even to Joses without Simon, we add the sisters, or Clopas their father, or (as Grotius suggests) other more remote relatives, as constituting the ἀδελφοὶ who manifested unbelief on the former occasion; and if to the same Joses and Simon, or Joses singly, we add others of the same class, but not necessarily identical with the former individuals, as making up those ἀδελφοὶ who in Acts i. 14, and on subsequent occasions, are distinguished as a class of the faithful from the Apostles.

II . While it is from the first two Gospels that we obtain the names of the four brethren, James, Joses, Simon, and Judas; and also the correct notion of their parentage, in the statement that the mother of the two first-named was another Mary; it is somewhat perplexing to find that by these Evangelists only is the last of the four not thus named in the list of the Twelve: that whereas St John mentions Jude as an Apostle, and St Luke twice includes him in their catalogue as “Jude the brother of James,” placing him next after James and Simon Zelotes, the two earlier Evangelists place him between the same James and Simon, under the different name of Thaddeus; St Matthew adding also a third name, Lebbæus.

Perhaps, when the treason of Judas Iscariot was yet recent, there might be a reluctance, unfelt at the period when St Luke, and St John, and St Jude himself wrote, to use in the designation of an Apostle a name that might lead the readers to think of the traitor, (St John himself thinking it necessary to say ” Judas, not Iscariot“): while in recording the speech of the men of Nazareth, it was not necessary to forbear the use of the more ordinary well-known name of the person in question; which continued even to the last to be his usual proper designation. No more need be said on this singular circumstance; which, considering the frequency of plurality of names among the Jews, and the indubitable identity of the possessor of these three names, Lebbæus, Thaddæus, and Judas, scarcely amounts to a difficulty. . . .

The fourth and last circumstance, which must be stated as a difficulty in the way of the conclusion here drawn from the scattered notices in the New Testament, and the vestiges of primitive belief on that subject, is the concurrence with this at a very early period, in the Eastern Church especially, of an entirely different opinion respecting these brethren and sisters of our Lord: I mean the opinion which makes them the children of Joseph the carpenter by another wife, prior to his espousal of the blessed Virgin, and which consequently distinguishes St James the Just our Lord’s brother from the Apostle St James the Less, the son of Alphæus. . . .

It is remarkable that these brethren are never termed the sons of Joseph; and that they are named but once, and then but indirectly or mediately, in connexion with him [Viz. in Matth. xiii. 55, where,though Jesus is termed by the Nazarenes “the carpenter’s son,” the brotherhood of James and the rest is connected with the mention of his mother rather than of Joseph: as we find in all the other places, xii. 46; Mark iii. 31, vi. 3; Luke viii. 19; John ii. 12.]; whereas they are repeatedly mentioned in direct association with Mary, and though never called her children, are yet spoken of nearly as they would have been had they been hers. But excepting this circumstance, (of which the widowhood of Mary and headship in the household of the deceased Joseph may well be taken as a sufficient account), this hypothesis is far more agreeable to the Gospel, when carefully examined, than the one that has been refuted [i.e., that Jesus had true siblings, or the “Helvidian” view]. . . .

The circumstance . . . that the first Bishop of Jerusalem was not to harbour his father’s wife, by whom he had been on this hypothesis supported from early infancy, is surely left by it without adequate explication: for no real solution of the difficulty is obtained even from the strange hypothesis to which the modern Helvidians have had recourse, that St James and the other supposed sons of Joseph were reclaimed from absolute unbelief in Christ between the resurrection and the ascension.

This however is but the commencement of improbabilities. There follows the necessity of maintaining that he was not an Apostle whom St Paul not only so describes to the Galatians, but ranks with St Peter and St John as a chief pillar of the Church, and apostle of the circumcision: that while beside the son of Zebedee, there was certainly another called James, and surviving the former, among the chosen twelve, and also a “Jude the brother of James,” the James here distinguished as extra-Apostolic so far eclipses the estimation of that Apostle, that when his brother Jude likewise writes authoritatively to the Jewish Church of the dispersion, he styles himself, as by distinction from every other of his common name, Jude the brother of James–thus appropriating the very designation which is twice attached by St Luke to another Jude the brother of another James, both Apostles of Christ’s own selection to convert the world.

And this hypothesis at the same time requires us to believe that when St Matthew speaks of ” Mary the mother of James,” he does not there mean the James whose fame has thus obscured every other James in the Jewish Church, for which he was particularly writing-not even though he adds there (xxvii. 56,) “the mother of James and Joses,” and had before confessedly assigned to this same distinguished James a brother named Joses (xiii. 55); but here–for the very purpose of distinguishing that hitherto unmentioned Mary-he is calling her the mother of another James, viz. the eclipsed son of Alphæus, and of another Joses his brother. I do not say that these things are incapable of being proved: I only assert that the necessity of admitting them should be most decided and unquestionable, to overcome their great apparent improbability.