Admirable Ecumenical Sentiments; Mary as Our “Hope” & “Refuge” & “Comfort”; Must We Always Know of Mary’s Co-Mediation?

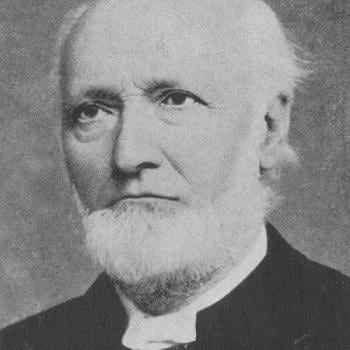

Edward Bouverie (E. B.) Pusey (1800-1882) was an English Anglican cleric, professor of Hebrew at Oxford University for more than fifty years, and author of many books. He was a leading figure in the Oxford Movement, along with St. John Henry Cardinal Newman and John Keble, an expert on patristics, and was involved in many theological and academic controversies. Pusey helped revive the doctrine of the Real Presence in the Church of England, and because of several other affinities with Catholic theology and tradition, he and his followers (derisively called “Puseyites”) were mocked by over-anxious adversaries in 1853 as “half papist and half protestant”. But, unlike Newman and like Keble, he never left Anglicanism.

I continue my replies to Pusey by examining a few portions of his follow-up volume, First letter to the Very Rev. J. H. Newman, D.D., in explanation chiefly in regard to the reverential love due to the ever-blessed Theotokos, and the doctrine of Her Immaculate Conception (London: Rivingtons, 1869; aka Eirenicon, Pt. II). He described Newman in the beginning of his letter as his “dearest friend” and a person “whom I still admire as well as love” and he fondly recalled the “sunny memories” of their time together in the Oxford Movement and rejoiced that they were still comrades-in-arms “against unbelief.” It’s an ecumenical model we can all admire, and should seek to emulate. Pusey’s words will be in blue. The larger series will be collected under the “Anglicanism” section of my Calvinism and General Protestantism web page, under his name. I use RSV for Bible citations.

*****

The Church of England does hold a Divine authority in the Church, to be exercised in a certain way, deriving the truth from Holy Scripture, following Apostolical tradition, under the guidance of God the Holy Ghost. I fully believe that there is no difference between us in this. The “quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus,” [“that which was believed everywhere, always, and by all”] which our own Divines have so often inculcated, contains, I believe, the self-same doctrine as is laid down in the Council of Trent upon tradition. (pp. 4-5)

This shows that High Anglicans or Anglo-Catholics, hold the same view on the rule of faith that we do, over against sola Scriptura.

My book [An Eirenicon, 1864] had necessarily a two-fold aspect. It was a defence of ourselves against what, amid all courteousness of language, was a root-and-branch attack upon the Church of England, . . . I claimed to her all the broad outlines of faith which you too have, and, (as I trust, truly,) I set aside many things which are the ordinary subjects of Protestant attack upon you. (p. 6)

This is true. Pusey’s criticisms are some of the most articulate and reasoned and bigotry- and falsehood-free observations about Catholicism that I have seen from a Protestant in my 34+ years as a Catholic. He disagrees in all good faith and honesty and he does so with class and a lack of all acrimony and derision. What a breath of fresh air! Pusey is to be highly commended for this and it’s a pleasure to interact with his thoughts.

I meant to suggest, that this state of things was not irremediable; that there was a way, whereby peace and intercommunion might be restored, through mutual explanations, without calling upon the Church of Rome to abandon any thing which she had pronounced to be “de fide.” (p. 7)

It’s certainly a worthy goal. How sad and discouraging, however, to think upon how much the Church of England has changed — in a heterodox direction — from 1869 up to the present time, where the prospect of such unity and reunion would be the most distant pipe-dream at best. I believe that Pusey, like C. S. Lewis, would certainly be a Catholic if he had the choice that would be presented to him today. The Protestant body that is closest to the Catholic Church in its thinking now is the conservative wing of Lutheranism, though there are still small bodies of separatist traditional orthodox Anglicans that have separated themselves from their mother-communion.

I simply wished to exhibit the picture of practical devotion to the Blessed Virgin, as it was reflected to me in their writings, and it did not even occur to me that I could be thought thereby to pass any opinion as to the inner life of those whose words were cited. When I heard that my not expressing this was thought to be unjust to holy men whom I quoted, I took the first opportunity which occurred to say, that I did not mean, to impute to any, of them that “they took from our Lord any of the love which they gave to His Mother.” (p. 8)

This is the very model of charity in theological dialogues: assuming the best of the opponent and not attributing to him ill will or ill motives or insincerity. It’s not surprising that it’s an exchange between men who had been, and continued to be, good friends. Would that all dialogue could be of this sublime nature!

Pusey critiques what he thinks is the excessive Marian veneration of St. Alphonsus de Liguori in his Glories of Mary, on pages 9-10. I have explained in several papers that this perceived-to-be-extreme-and blasphemous language has to be understood within the backdrop of St. Alphonsus’ repeated statements and reiterations in the same book of the primacy of Jesus Christ. See:

St. Alphonsus de Liguori: Mary-Worshiper & Idolater? [8-9-02]

It seems to me, that the writer, in his vehement desire to set forth the privileges of Mary, contradicted the truth which he himself held, if he believed that the mercy of Jesus could save them. (p. 10)

This is relatively more accurate, but I submit that the problem isn’t contradiction in the Catholic writer; rather, it’s misunderstanding of the overall theology and veneration of the Catholic writer by the Anglican reader. There are two different ways to look at almost anything.

But my object was a practical one. I knew that in thousands of English minds (I doubt not, that in millions), this and the like language is the great barrier against re-union. (p. 10)

All the more reason to take the greatest pains to try to understand and comprehend the writing and worldview which is so vehemently disagreed with . . . I think articles such as mine, above, can help Protestants today to do exactly that. But it takes an open and willing mind.

I have often (though you will smile perhaps at the advocacy) had to defend the Roman Church against being idolatrous, and that, on the ground of this and the like language. (p. 10)

Then he was predisposed to be open to an agreeable explanation for what he thinks are Marian “excesses.” But if the brilliant Cardinal Newman couldn’t persuade him, I doubt that anyone else ever could (and apparently no one did, or else he would have converted to Catholicism, too). There are many of us — including myself — who have made the move from a much more distant Protestantism to Catholicism, without any insuperable intellectual difficulties. It’s entirely possible.

. . . (in your Bishop Milner’s words which I have already quoted,) ” That, as the saints in Heaven are free from every stain of sin and imperfection, and are confirmed in grace and glory, so their prayers are far more efficacious for obtaining what they ask for, than are the prayers of us imperfect and sinful mortals.” If this had been all, I have expressed my conviction that the difficulty never would have arisen. (pp. 35-36)

There still, indeed, remain the difficulties of some titles, which do not occur in the Fathers, and which one would have expected rather to be given to our Lord ; Health of the weak, Refuge of sinners, Comforter of the afflicted, Help of Christians . . .

This title, “Refuge of sinners,” is, accordingly, the text on which S. Liguori puts together the passages of middle-age writers, or such as are attributed wrongly to the Fathers, which speak of her as the Hope of Sinners.” Such sinners seem to be spoken of as out of the reach of Jesus, or hopeless of His help, and Mary seems to be held out to them as the way by which they are to approach to Jesus. (p. 37)

I don’t see that this is beyond what the Bible says about great prayer warriors. In my Reply #2 to Pusey, I went through a long list of such holy and powerful people. When, for example, God told Abimelech that Abraham would pray for him, so he could live, “for” Abraham was “a prophet” (Gen 20:6-7), would it not have been appropriate and fitting for Abimelech to consider Abraham his “hope” or “refuge” or “help”? I think it makes perfect sense. And so we consider Mary a hope and help and refuge in this very sense: her extraordinary holiness helps make her prayers much more powerful. Pusey recognized the premise of this principle of prayer in his words from pages 35-36 above (derived from James 5:16).

Likewise, when “All Israel” (1 Sam 12:1) “said to Samuel [the prophet], ‘Pray for your servants to the LORD your God, that we may not die’. . .” (1 Sam 12:19), would it not have made perfect sense for them to regard Samuel as their “hope of sinners” or “refuge” or “help”? Why couldn’t this be, then, also applicable to the far holier and indeed sinless and immaculate Mary? Further, when God’s “anger was kindled, and the fire of the LORD burned among them” and as a result, “the people cried to Moses; and Moses prayed to the LORD, and the fire abated” (Num 11:1-2), who could argue that they couldn’t possibly have regarded Moses as their “hope of sinners” or “refuge of sinners” or “help”? He saved their lives, and possibly saved them from eternal damnation! How is that not being “hope” or “refuge” or “help”?

St. Paul wrote in some depth about the “comfort” that his suffering and work had been to the Corinthian Christians, even unto their “salvation”:

2 Corinthians 1:3-7 Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of mercies and God of all comfort, [4] who comforts us in all our affliction, so that we may be able to comfort those who are in any affliction, with the comfort with which we ourselves are comforted by God. [5] For as we share abundantly in Christ’s sufferings, so through Christ we share abundantly in comfort too. [6] If we are afflicted, it is for your comfort and salvation; and if we are comforted, it is for your comfort, which you experience when you patiently endure the same sufferings that we suffer. [7] Our hope for you is unshaken; for we know that as you share in our sufferings, you will also share in our comfort.

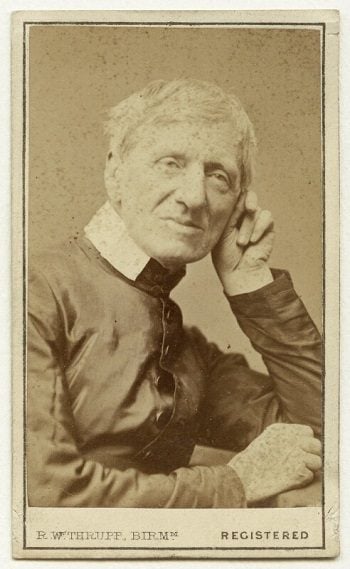

Photo credit: photograph of St. John Henry Cardinal Newman (1801-1890) from 1866, three years before E. B. Pusey’s long letter to him. [public domain]

Summary: This is a reply to a few portions of E. B. Pusey’s “First letter to the Very Rev. J. H. Newman” (1869), dealing with the veneration of Mary and her Immaculate Conception.