Also Including Analysis of Josephus’ and Philo’s Views, Jewish Scholars at Jamnia (c. AD 90), and the Qumran Community

Norman L. Geisler (1932 – 2019) was an American evangelical Protestant theologian, philosopher, and apologist. He obtained an M.A. in theology from Wheaton College and a Ph.D. in philosophy from Loyola University, and made scholarly contributions to the subjects of classical Christian apologetics, systematic theology, philosophy of religion, Calvinism, Catholicism, biblical inerrancy, Bible difficulties, biblical miracles, the resurrection of Jesus, ethics, and other topics. He wrote or edited more 90 books and hundreds of articles.

Dr. Geisler was the Chairman of Philosophy of Religion at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School (1970–79) and Professor of Systematic Theology at Dallas Theological Seminary (1979–88) and a key figure in founding the Evangelical Philosophical Society. He also co-founded Southern Evangelical Seminary. He was known as an evangelical Thomist and considered himself a “moderate Calvinist”. He was not an anti-Catholic (i.e., he didn’t deny that Catholicism was fully a species of Christianity).

This is one of a series of comprehensive replies to his book, Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences (co-author, Ralph E. MacKenzie, graduate of Bethel Theological Seminary-West; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 1995). It’s available online in a public domain version, which has no page numbers, so I will utilize page numbers from my paperback copy, for the sake of full reference. I consider it the best Protestant critique of Catholicism (especially in terms of biblical arguments) that I have ever found, from any time period. The arguments are, for the most part, impressively presented, thought-provoking, respectful, respectable, and worthy of serious consideration (which I’m now giving them).

I’ll be concentrating on the eight sections of Part Two: “Areas of Doctrinal Differences” (202 pages). These installments will be listed and linked on my Calvinism & General Protestantism web page, in section XVII: “Catholics and Protestants” (second from the end). Dr. Geisler’s and Ralph MacKenzie’s words will be in blue. My biblical citations are from RSV.

*****

Actually, all that the arguments used in favor of the canonicity of the apocryphal books prove is that various apocryphal books were given varied degrees of esteem by different persons within the Christian church, usually falling short of canonicity. Only after Augustine and the local councils he dominated mistakenly pronounced them inspired did they gain wider usage and eventual acceptance by the Roman Catholic Church at Trent. This falls far short of the kind of initial, continual, and complete recognition of the canonical books of the Protestant Old Testament and Jewish Torah (which exclude the Apocrypha) by the Christian church. It exemplifies how the teaching magisterium of the Catholic church proclaims infallible one tradition to the neglect of strong evidence in favor of an opposing tradition because it supports a doctrine that lacks any real support in the canonical books. (p. 165)

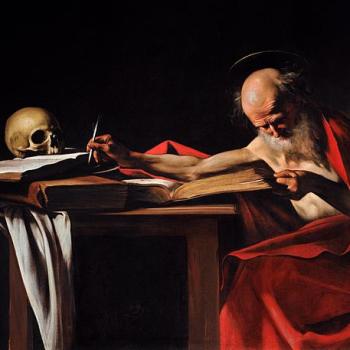

Geisler wars against himself here, as I will now proceed to demonstrate. He claims that the “evidence” supports the Protestant OT canon. He cites in its favor the advocacy (or supposed advocacy) of “Jerome . . . Origen, Cyril of Jerusalem, and Athanasius” (p. 166). These are the same four fathers that he had already cited on page 162 as being “opposed” to the deuterocanon; and he cites the same four — for the same purpose — for a third time on page 169, and three (minus Origen) on page 171. I have four responses to this:

1) Merely repeating a falsehood makes it no more true or no less false than it was in the beginning. In my installment #4 I already dealt with Jerome, Athanasius, and Origen (and will address St. Cyril’s views in due course as well), and showed that a straight description of their view as “opposed” is unwarranted. If Geisler were so sure and confident about patristic consensus, surely he could cite many more Church fathers on his side, but as it is he names merely four men, three times. This certainly suggests a great weakness in his position, since if more support existed, as is required in this debate, surely he would have brought it forward.

2) Even if Dr. Geisler were correct about the views of these four men (which I deny), “four Church fathers do not a patristic consensus make.” It’s silly to even imply such a thing; in fact, it is an insult to the intelligence of any reader who has studied the Church fathers and/or who understands how the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox think about their authority. We regard a consensus of the Church fathers as highly significant, in terms of what is likely true. But four Church fathers obviously don’t constitute a consensus. There are at least fifty major Church fathers (I think most would agree). So four out of fifty is a mere 8%, if we use the estimate of fifty.

3) Dr. Geisler’s and other Protestant’s defenses of the “protocanon” of the OT relies precisely on the widespread consensus of the Church fathers. This is why they accept the books that they do; and we fully agree as far as these books go; we simply think seven more should be included. But Geisler applies a glaring double standard. When he writes elsewhere about patristic support for the protocanon (such as in his book How We Got the Bible), he names many Church fathers, and assumes that this makes a strong case (as indeed it does). Yet then when it comes to opposition (or supposed opposition) to the deuterocanon, he can only come up with four. This won’t do. Consensus is what it is, and four men isn’t that. Geisler himself refers above to “initial, continual, and complete recognition of the canonical books of the Protestant Old Testament” and “strong [patristic] evidence.” Thus, the very fact that he produces so many in one case and only four in the other, proves that his point of view (i.e., the standard Protestant one) is so weak that it ought to be rejected.

4) It’s an old, obnoxious, Protestant apologetical tactic, I’m afraid — and I’m in a good position to be aware of this, as a Catholic apologist these past 35 years — to make a great deal of one or a few exceptions to the rule, if many Church fathers cannot be produced in support of a particular novel and late-arriving Protestant view. In discussions of the OT canon, St. Jerome is always highlighted by the Protestant apologist, even though his opposition is not uniform or consistent; and St. Augustine (widely considered the greatest Church father in both camps) is minimized, because he strongly advocated the Catholic and Orthodox view. Protestants themselves usually try to argue from the consensus of the Church fathers regarding many doctrines, so it’s silly — and even embarrassing — to assume that one (Jerome) or just four fathers is definitive as to the deuterocanon. But this is what is done: if no consensus can be found, then they major on the minors and discuss just a few. But this is contrary even to their own ostensible patristic outlook and is self-defeating.

I’ve already in this series given documentation on this score from Jerome, Athanasius, Origen, Clement of Rome, The Shepherd of Hermas, and The Didache, and I’ll proceed now with many more citations, showing where the patristic consensus actually lies. It’s no mystery. For example, Anglican patristics scholar and Principal of St Edmund Hall, Oxford, J. N. D. Kelly (1909-1997) states:

The Old Testament thus admitted as authoritative in the Church . . . always included, though with varying degrees of recognition, the so-called Apocrypha, or deutero-canonical books. (Early Christian Doctrines, New York: Harper & Row, 2nd edition, 1960, p. 53)

In the first two centuries at any rate the Church seems to have accepted all, or most of, these additional books as inspired and to have treated them without question as Scripture. Quotations from Wisdom, for example, occur in 1 Clement and Barnabas, . . . Polycarp cites Tobit, and the Didache Ecclesiasticus. Irenaeus refers to Wisdom, the History of Susannah, Bel and the Dragon and Baruch. The use made of the Apocrypha by Tertullian, Hippolytus, Cyprian and Clement of Alexandria is too frequent for detailed references to be necessary. (p. 54; see primary references in the online book, linked above)

Kelly goes on (pp. 54-55) to cite Augustine (“whose influence in the West was decisive”), Hilary, John Chrysostom, Origen, and Theodoret as of essentially the same opinion. That adds (including The Shepherd of Hermas, that I noted) up to at least 15 Church fathers or early treatises in favor of the deuterocanon. He also names others as opposed (Athanasius, Cyril of Jerusalem, Gregory Nazianzus, Epiphanius, Rufinus, Melito, and John Damascene). So that is — so far — 15 “pro” and 7 “con”: a 2-to-1 ratio or 68.2% to 31.8%: which is clearly a consensus towards the “pro” view, as verified also by his broad description of the view of the early Church.

Catholic apologist Gary Michuta documents the views of Church fathers in this respect in great depth, in his books, Why Catholic Bibles are Bigger (Port Huron, Michigan: Grotto Press, 2007) and The Case for the Deuterocanon: Evidence and Arguments (Livonia, Michigan: Nikaria Press, 2015). Here is a handy summary of the views of many fathers not mentioned above (and many that were listed as “opposed”):

1) Athenagoras cites Baruch 3:36 alongside citations of Isaiah, not indicating any difference. (Bigger, 76-77; Case, 112)

2) The Catacombs (2nd-3rd centuries) includes images drawn from Susannah, Bel and the Dragon, and Tobit (Bigger, 79-80)

3) Dionysius the Great cites Tobit and Wisdom and introduces Sirach as “divine oracles.” (Bigger, 98-99)

4) Archelaus, bishop of Mesopotamia, cites Wisdom 1:13 as an authority on doctrine. (Bigger, 99-100)

5) Lactantius cites Sirach to confirm doctrine. (Bigger, 101-102)

6) Aphraates the Persian refers to the martyrdoms of the Maccabees and quotes Sirach 29:17, seemingly not distinguishing them from the authority of the books of the protocanon. (Bigger, 103)

7) Alexander of Alexandria cites Sirach alongside 1 Corinthians, regarding the doctrine of God’s incomprehensibility. (Bigger, 104-105)

8) Cyril of Jerusalem includes Baruch in his protocanon, and stated that the deuterocanonical books, though “secondary” could be read in churches. He himself cited Wisdom and Sirach for doctrinal instruction and considered the deuterocanonical sections of Daniel as authentically part of that book, and sometimes cited them with the introduction, “It is written . . .”(Bigger, 114-117)

9) Basil the Great cites Judith, Wisdom, Baruch, and the deuterocanonical chapters of Daniel in a manner no different than the rest of Scripture (Bigger, 121-12)

10) Gregory Nazianzus cites Baruch 3:35-37 concerning the Trinity and often cites Wisdom and Sirach without qualification. He regards the deuterocanonical chapters of Daniel as part of that book. He introduces a passage from Judith as having been taken from “Scripture.” In the context of listing great figures of the Old Testament, he includes the seven Maccabean martyrs. Then he goes on to cite examples in the New Testament, suggesting all as part of what Holy Scripture describes. (Bigger, 122-125)

11) Epiphanius was inconsistent. He compiled three list of canonical books, but they disagree with each other (as to the status of Baruch, the Letter of Jeremiah, Sirach, and Wisdom. In his work, Adversus Haereses 76.5 he even describes Wisdom and Sirach as among “the books of Scripture” and he does this in other places as well, and wrote of Wisdom, that it “has come from the mouth of the Holy Spirit.” He introduces Maccabees and the “extra” sections of Daniel with the formula, “It is written . . .” He describes Baruch as part of the “Scriptures.” (Bigger, 127-130)

12) Ambrose views Baruch as part of Jeremiah. He cites Tobit as a prophetic book. He quotes Wisdom as “Scripture”, with the introduction of “It is written . . .” (as he does also with 2nd Maccabees), and writes that Wisdom contains the words of the Lord. He calls Sirach “Scripture” and accepts the deuterocanonical sections of Daniel as part of that book. (Bigger, 131-133)

13 Rufinus refers to Baruch as the words of Jeremiah. He refers to Sirach as both “Scripture” and “sacred Scripture.” Wisdom is said to contain prophecy. He regards the entire (Catholic) book of Daniel as the “deposit of the Holy Spirit.” (Bigger, 134-138)

14) John Cassian quotes Sirach and Wisdom as “Scripture.” (Bigger, 165-166)

15 Vincent of Lerins refers to Sirach as one of “the divine oracles” alongside Proverbs and Ecclesiastes. (Bigger, 166-167)

16) Leontius cites Sirach, Wisdom, and Baruch as Scripture. He utilizes Wisdom to affirm the consubstantiality of the Son. (Bigger, 173-174)

17) Gregory the Great introduces Wisdom with “It is written . . ” about sixteen times. (Bigger, 175-178)

18) Isidore of Seville listed as “books of the Old Testament” and “divine books” Wisdom, Sirach, Tobit, Judith, and 1 and 2 Maccabees, refers to “seventy-two canonical books.” In his Prologue to the Old Testament he mentions that “the Hebrews do not receive Tobias, Judith, and Maccabees, but the Church ranks them among the Canonical Scriptures . . . these are acknowledged to have, in the Church, equal authority with the other Canonical Scriptures.” (Bigger, 181-183)

19) John Damascene described Wisdom 3:1 as “divine Scripture” and Baruch in the same way, in a quote appearing between Psalms 14:7 and 137:1. He uses 2nd Maccabees to support the doctrine of God’s omniscience. (Bigger, 189-190)

20) Methodius states that Wisdom is “a book full of virtue, the Holy Spirit openly drawing his hearers” and cites Wisdom and Sirach as “Scripture” (Case, 118-119)

21) Gregory Nyssa describes Wisdom 1:4 as “Scripture.” (Case, 123)

22) Didymus the Blind cites Tobit 12:8-9 as “divinely-inspired Scripture,” Judith as part of the “Old Testament,” Sirach as “Scripture.” (Case, 123)

23) Theophilus of Alexandria cites Wisdom 1:7 as “Scripture.” (Case, 134-135)

24) Sulpitius Severus describes Tobit and the Maccabees as “Scripture.” (Case, 135)

25) Cyril of Alexandria cites Sirach 3:22 as “Sacred Scripture” and Baruch and Wisdom as “Scripture.” (Case, 136)

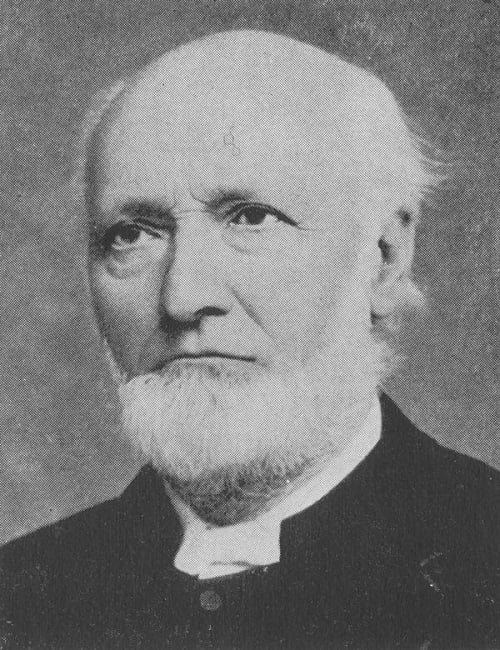

The eminent Protestant Church historian Philip Schaff (1819-1893; see much more about him), editor of the standard 38-volume set of the Church fathers, in his History of the Christian Church, Vol. 2 (of 8), leaves little doubt as to the history of the Old Testament canon, including the books disputed by Protestants:

The canon of the Old Testament descended to the church from the Jews, with the sanction of Christ and the apostles. The Jewish Apocrypha were included in the Septuagint and passed from it into Christian versions. . . .

The Catholic canon thus settled remained untouched till the time of the Reformation when the question of the Apocrypha and of the Antilegomena was reopened . . .

Soon after the middle of the fourth century, when the church became firmly settled in the Empire, all doubts as to the Apocrypha of the Old Testament and the Antilegomena of the New ceased, and the acceptance of the Canon in its Catholic shape, which includes both, became an article of faith. The first Ecumenical Council of Nicaea did not settle the canon, as one might expect, but the scriptures were regarded without controversy as the sure and immovable foundation of the orthodox faith.

Philo does indeed quote a lot of Scripture. He makes about 2,000 quotations in all. . . . [but] out of these 2,000 quotations 1,950 of them come from the first five books of the Bible known as the Pentateuch. The remaining 50 quotations come from the rest of the Old Testament. (The Case for the Deuterocanon: Evidence and Arguments, Livonia, Michigan: Nikaria Press, 2015, 70-71)

Philo, in his extant works, makes no mention of Ezekiel, Daniel, or the Five Rolls [i.e., Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Esther]. Since, however, even Sirach mentions Ezekiel, Philo’s silence about him is undoubtedly accidental; consequently, his failure to name the other books can not be taken as a proof that they were not in his canon.

In Josephus . . . we meet with variations in the history which suggest textual sources not now at hand . . .*That Josephus used the Additions after the recension A. is universally acknowledged. (p. 204)

The history has received the confirmation of the Talmudic tradition, and Josephus accorded it an apparently unlimited confidence. (p. 478)

Josephus (“Contra Ap.” i. 8), about the year 100, counted twenty-two sacred books. . . . It is not known with certainty what books were included. It is probable, however, that Lamentations and Baruch formed one book with Jeremiah, and . . . Esther still seems to have had its additions.

The so-called Council of Jamnia (c. A.D. 90), at which time this third section of writings is alleged to have been canonized, has not been explored. There was no council held with authority for Judaism. It was only a gathering of scholars. This being the case, there was no authorized body present to make or recognize the canon. Hence, no canonization took place at Jamnia. (From God to Us: How we Got our Bible, co-author William E. Nix, Chicago: Moody Press, 1974, 84)

It is probably unwise to talk as if there was a Council or Synod of Jamnia which laid down the limits of the Old Testament canon . . .A common, and not unreasonable, account of the formation of the Old Testament canon is that it took shape in three stages . . . The Law was first canonized (early in the period after the return from the Babylonian exile), the Prophets next (late in the third century BC) . . . the third division, the Writings . . . remained open until the end of the first century AD, when it was ‘closed’ at Jamnia. But it must be pointed out that, for all its attractiveness, this account is completely hypothetical: there is no evidence for it, either in the Old Testament itself or elsewhere. We have evidence in the Old Testament of the public recognition of scripture as conveying the word of God, but that is not the same thing as canonization. (The Canon of Scripture, Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1988, 34, 36)

The discoveries made at Qumran, north-west of the Dead Sea, in the years following 1947 have greatly increased our knowledge of the history of the Hebrew Scriptures during the two centuries or more preceding AD 70 . . . All of the books of the Hebrew Bible are represented among them, with the exception of Esther. This exception may be accidental . . . or it may be significant: there is evidence of some doubt among Jews, as latter among Christians, about the status of Esther . . .

But the men of Qumran have left no statement indicating precisely which of the books represented in their library ranked as holy scripture in their estimation, and which did not . . .

But what of Tobit, Jubilees and Enoch, fragments of which were also found at Qumran? . . . were they reckoned canonical by the Qumran community? There is no evidence which would justify the answer ‘Yes’; on the other hand, we do not know enough to return the answer ‘No’. (Ibid., 38-40)

As Athanasius includes Baruch and the ‘Letter of Jeremiah’ . . . so he probably includes the Greek additions to Daniel in the canonical book of that name, and the additions to Esther in the book of that name which he recommends for reading in the church, . . . Only those works which belong to the Hebrew Bible (apart from Esther) are worthy of inclusion in the canon (the additions to Jeremiah and Daniel make no appreciable difference to this principle) . . .*In practice Athanasius appears to have paid little attention to the formal distinction between those books which he listed in the canon and those which were suitable for the instruction of new Christians [he cites Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom of Sirach, Esther, Judith, and Tobit] . . . and quoted from them freely, often with the same introductory formulae – ‘as it is written’, ‘as the scripture says’, etc. [footnote 46: He does not say in so many words why Esther is not included in the canon . . . ] (Bruce, ibid., 79-80)

received by the Apostles from the mouth of Christ himself, or from the Apostles themselves, the Holy Ghost dictating” and “have come down even unto us, transmitted as it were from hand to hand; (the Synod) following the examples of the orthodox Fathers, receives and venerates with an equal affection of piety, and reverence, all the books both of the Old and of the New Testament–seeing that one God is the author of both” and that they were “dictated, either by Christ’s own word of mouth, or by the Holy Ghost, and preserved in the Catholic Church by a continuous succession.

First Vatican Council (1870)

These the Church holds to be sacred and canonical; not because, having been carefully composed by mere human industry, they were afterward approved by her authority; not because they contain revelation, with no admixture of error; but because, having been written by the inspiration of the Holy Ghost, they have God for their author, and have been delivered as such to the Church herself. (Dogmatic Constitution on the Catholic Faith, chapter II; emphasis added)

Second Vatican Council (1962-1965)

The divinely-revealed realities which are contained and presented in the text of sacred Scripture, have been written down under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. For Holy Mother Church relying on the faith of the apostolic age, accepts as sacred and canonical the books of the Old and New Testaments, whole and entire, with all their parts, on the grounds that they were written under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit (cf. Jn. 20:31; 2 Tim. 3:16; 2 Pet. 1:19-21; 3:15-16), they have God as their author, and have been handed on as such to the Church herself. (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation [Dei Verbum], Chapter III, 11; emphasis added)

No book of the Bible claims itself to be divinely inspired. Divine inspiration means that God himself authored the exact words of the text (using the human writer’s mind, personality, and background), and no book states anything like, “The words of this book were chosen by God” or “This book is divinely inspired.”

The term “inspired” (Greek, theopneustos) only occurs once in the Bible (2 Tm 3:16), where we are told that all Scripture is inspired. We first know that something is Scripture and then infer that it is inspired; we do not first know that it is inspired and then conclude it is Scripture.

The only non-technical references to inspiration occur when one book of the Bible reports that God or the Spirit spoke through the words of a different book (for example, see Heb 3:7-11, concerning Ps 95). In no case does a book of the Bible state this for itself. Even if it does claim to contain divine revelations or visions (as does the book of Revelation), it does not say of itself that every word of its text was inspired. That is something we must infer from 2 Timothy 3:16. Since no protocanonical book of the Bible meets [this] test, it can scarcely be expected of the deuterocanonical books.

Claiming to be inspired is a different thing from really being inspired [too]. The Book of Mormon claims to be the Word of God, but isn’t; the Gospel of John doesn’t, but it is.