These accounts are interesting, among other reasons, because the story of one miracle is contained within the story of another.

I’ll concentrate on just one of them here.

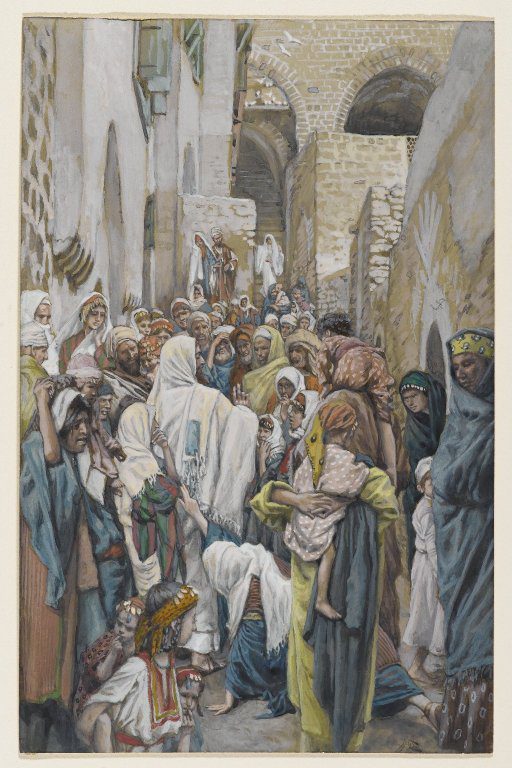

Try to imagine the case of the woman with a hemorrhage. For twelve years. One hundred and forty-four months. Six hundred and twenty-four weeks.

Near financial ruin. (She had, the accounts say, spent nearly everything she had.) And still getting worse, the gospels tell us.

Ritually unclean, too. Therefore unmarriageable. A social outcast. And, even if already married, unable to bear children.

Yet the mere faithful touch of Jesus’ garment heals her.

But he perceives that “virtue” has gone out of him.

Does that mean that he’s lost something of his goodness?

No. Virtue here means power. (Shakespeare speaks fairly often of the “virtue” of herbs and potions.)

In fact — and ironically despite the tendency of our sexist culture to connect it more with women than with men — it’s originally connected with the notion of “manliness.” Vir, in Latin, means “man,” in the sense of a masculine human. Think, too, of the cognate word werewolf, or “man-wolf.” (I once made this explanation in a Gospel Doctrine class and failed to erase the words virtue and werewolf from the blackboard. I’m told that when a different ward’s Relief Society came into the room after I was done, they were very puzzled — understandably so — as to what kind of lesson had just been taught there.)

We’ll return to the story of Jairus’s daughter at a later point.

Posted from Monterey. California