Wikimedia Commons public domain

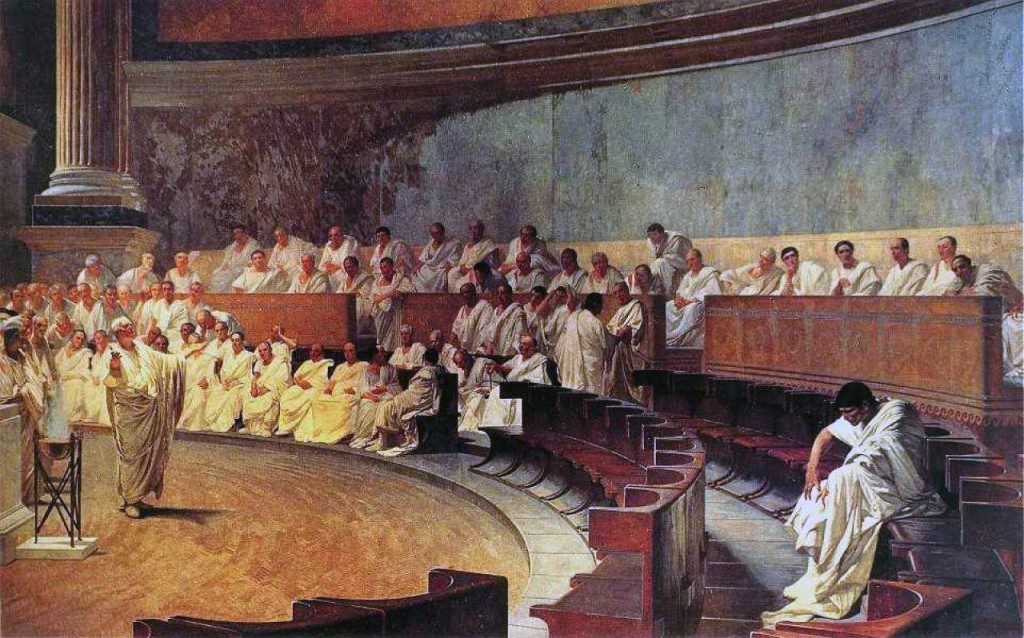

In his treatise Cato Maior de Senectute — generally called, in English, On Old Age — the Roman orator, master Latin prose stylist, philosopher, and statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero writes about a semi-legendary figure from even earlier Roman history by the name of Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus.

Widely respected in Rome for his successful battle to save the Roman Republic from the conspiracy led by Catiline to overthrow it, Cicero was eventually assassinated in 43 BC by order of Marc Antony because of his defense of the Senate and of the Republic and his resistance to the dictatorial Second Triumvirate. He was one of the last major voices to resist the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire.

By means of his account of Cincinnatus, Cicero encouraged his readers to remember what he saw as the simplicity of republican Rome. The senators of earlier times, he said, were modest farmers who preferred to cultivate their fields in peace, who were not ambitious for power but only engaged in public affairs when the state needed them, when the people implored them to act.

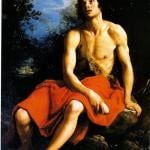

Cincinnatus was a Roman aristocrat in a time — during the fifth century BC — when social strife between patricians (the upper class) and plebeians (the lower class) was out of control. At one point, he himself went into voluntary exile and suffered financial ruin. Eventually, though, he returned to Rome, where he served as consul.

When his term was over, Cincinnatus returned to his farm. But strife continued and worsened, and eventually Rome’s weakness drew predatory attacks from external enemies, as well. The very survival of the nation was at stake. In such times of crisis, the early Roman practice was for the Senate to elect a dictator, with supreme power to take action in order to end the potentially lethal emergency.

Wikimedia Commons public domain

In 458 BC, the Roman Senate unanimously decided that Cincinnatus was the only man with the skills, the stature, and the integrity to save the state and the people from their peril. A party of Senators was sent to his farm, where they found him working at his plough. They explained the dangers that faced Rome and the urgent crisis that had newly arisen, and they implored him to save his country. He was both surprised at their choosing him and reluctant to accept the appointment. Finally, though, he did.

Cincinnatus took command of a Roman army, marched to where the currently-serving consul was trapped and besieged, and routed the enemy.

Two weeks later, he was back at his farm, having laid down his dictatorial powers.

With his modesty, his simplicity, and his spirit of patriotism and public service, Cincinnatus was venerated ever afterward as a moral example of how Roman noblemen should do their duty when their country needed them.

Americans often compared George Washington to Cincinnatus. What Washington wanted most was to be at Mount Vernon. But, when his country needed him, he answered the call, serving first as commander of the Continental Army against the British forces who were attempting to put down the American Revolution and then, having once more returned to his farm, accepting the unanimous vote of the Electoral College to serve as our nation’s first president.

And now . . .

With the story of Cincinnatus in mind, I give you Jay Cost’s appeal in the Weekly Standard, entitled “An Open Letter to Mitt Romney.”

In support of which, I offer David French’s uniquely informed reflection that

“An Independent Run is More Realistic Than You Think”