Continuing with the discussion that I began in a prior entry, “How can a Latter-day Saint entertain the possibility that Muhammad might have been a prophet? (Part One)”:

The Facebook comments from Richard Giroux appear in red. My one additional Facebook response will appear in green, while my responses here will simply appear in the ordinary default black.

“Truth exists independent of the speaker/messenger of it. According to the LDS canon, Satan spoke truth, accompanied by lies, to Adam and Eve in the Garden and also when tempting Jesus. By extension of your argument, people should welcome truth from whatever source–even from Satan.

My point is that it is hard to separate the message from the messenger. Belief that a messenger is a true prophet lends credence to his/her teachings.

Mormons validate the “truths” that others teach by comparison to the revealed truths that comprise Mormonism. I suspect that before you quoted the Qur’an in Church (presumably in the context of using it as a source of truth), you had vetted it against your own view of Mormon doctrine. In that way, the Qu’ran really didn’t add to your accepted collection of truths, but was used as another example to teach a truth that you already believed.

If a Mormon believes that Mohammed taught a truth, it is because it comports, or least does not conflict, with LDS teachings. It is quite another thing to accept Mohammed or anyone else as a prophet–and thereby accept his/her teachings with the same openness as the teachings of Joseph Smith.”

A number of others had weighed in on the discussion in the interim, so I indicated a degree of puzzlement:

“I’m not sure who it is that you think you’re debating with, Richard Giroux.”

“I am criticizing the points you made in your piece. Whether it is a debate or not depends on the willingness of someone else to take up the other side.

“A more general criticism starts with a straw man that you set up so as to provide contrast to what you assert is a Mormon ‘middle position.’ I consider myself reasonably well read, but I do not believe that there is much, if any, currency in society asserting that people such as Ghandi, Tolstoy or MLK are prophets. People are sometimes metaphorically called prophets, such as Warren Buffet being called the “Oracle of Omaha” but not in the sense that they are channeling some divine message that originates outside of their own rational processes.”

Okay. Now that things are a bit clearer, I’ll reply.

1.

Yes, I believe that people should welcome truth no matter whence it comes.

We certainly don’t believe in rejecting truth merely on account of its source. Two plus two will still equal four even if Satan says so. The fact that Goebbels and Stalin believed that circles contain 360 degrees and that Moscow is a Russian city doesn’t render those beliefs false.

2.

“I suspect that before you quoted the Qur’an in Church (presumably in the context of using it as a source of truth), you had vetted it against your own view of Mormon doctrine. . . . If a Mormon believes that Mohammed taught a truth, it is because it comports, or least does not conflict, with LDS teachings.”

There is some validity in that observation. I wouldn’t be inclined to regard or use a statement as “inspired” if (a) its inspiration were unestablished and (b) what it had to say clearly and directly conflicted with statements whose inspiration I regarded as securely established. But this is no different, really, than being reluctant to accept, say, a new and questionable historical source when it conflicts with an array of already-validated historical data. Likewise, if reliable witnesses had strongly testified to a fact in a criminal trial, a new and questionable contradictory witness would not likely overturn their testimony.

3.

“In that way, the Qu’ran really didn’t add to your accepted collection of truths, but was used as another example to teach a truth that you already believed.”

Well, yes and no.

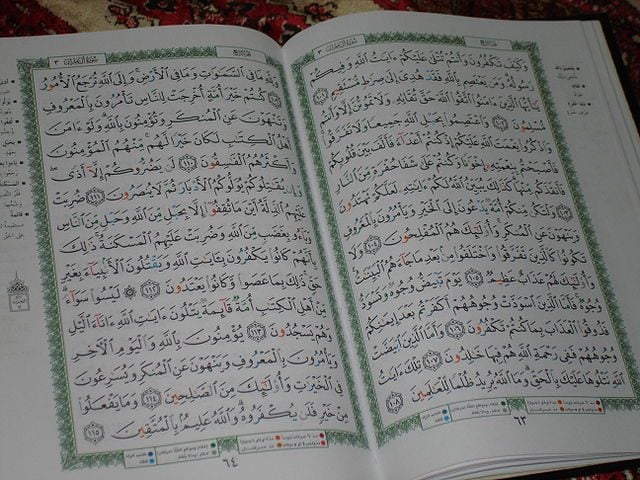

There are expressions in the Qur’an that are wonderfully eloquent. I find myself citing them sometimes — even in discussions on Mormon or other non-Islamic topics — to make a point when they seem better phrased than anything else I know.

There are also insights in the Qur’an that, in my judgment, might help in understanding Latter-day Saint beliefs/practices (including some temple issues). I’m working on a book (for a non-LDS audience) that will systematically deploy some of these insights. If any Latter-day Saints eventually read it, they’ll readily see what I mean.

4.

“If a Mormon believes that Mohammed taught a truth, it is because it comports, or least does not conflict, with LDS teachings. It is quite another thing to accept Mohammed or anyone else as a prophet–and thereby accept his/her teachings with the same openness as the teachings of Joseph Smith.”

I’ve not suggested that Latter-day Saints should accept the Qur’an (at least, as we currently have it) as scripture on a par with the four “standard works,” nor that they should regard Muhammad (at least, as we currently possess his teachings) as a prophet equally authoritative with Joseph Smith.

My view of the Qur’an (and its status for Latter-day Saints) is closely analogous to the view of the biblical apocrypha expressed in a revelation given through Joseph Smith at Kirtland, Ohio, on 9 March 1833, as he was working on what would eventually become the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible:

1 Verily, thus saith the Lord unto you concerning the Apocrypha—There are many things contained therein that are true, and it is mostly translated correctly;

2 There are many things contained therein that are not true, which are interpolations by the hands of men.

3 Verily, I say unto you, that it is not needful that the Apocrypha should be translated.

4 Therefore, whoso readeth it, let him understand, for the Spirit manifesteth truth;

5 And whoso is enlightened by the Spirit shall obtain benefit therefrom;

6 And whoso receiveth not by the Spirit, cannot be benefited. Therefore it is not needful that it should be translated. Amen.

5.

“A more general criticism starts with a straw man that you set up so as to provide contrast to what you assert is a Mormon ‘middle position.’ I consider myself reasonably well read, but I do not believe that there is much, if any, currency in society asserting that people such as Ghandi, Tolstoy or MLK are prophets. People are sometimes metaphorically called prophets, such as Warren Buffet being called the “Oracle of Omaha” but not in the sense that they are channeling some divine message that originates outside of their own rational processes.”

I deny that I set up a “straw man,” and I point out that — on the whole — we don’t really much disagree in this regard.

We do disagree, though, about whether people like Gandhi and Martin Luther King have been called “prophets.” In my experience, they have. And not uncommonly. (Perhaps Tolstoy, too, although I can’t offhand remember a particular case of that.)

But, yes, they’ve been called “prophets” more or less metaphorically. However, those who call them “prophets” not uncommonly have a similar view of many of the biblical prophets, as well. Amos and Micah were calling for social justice and reform, such folks say, in much the same way that Gandhi and Dr. King were seeking reform and social justice. Those who speak this way place much less emphasis on notions of literal and authoritative divine communication than Latter-day Saints typically do — and may not even believe in it at all. Thus, it’s not at all uncommon to hear that Nelson Mandela or Archbishop Desmond Tutu spoke “prophetically,” without there being the slightest hint that they received literal visions or propositional revelations from God.

I’ve been commenting on such usage for many years now, and this is the middle ground on which I see Latter-day Saints standing:

On the “left,” there are those who are willing to recognize “prophets” all around the world, in different religious and cultural traditions. In doing so, though, they tend to downplay the “literality” of revelation and prophethood — certainly in comparison to standard Latter-day Saint usage — and, very often (though this is less essential to my point), to privilege a “progressive” or “social justice” political sensibility.

Latter-day Saints share in that willingness to see inspiration and (sometimes) even prophethood beyond the confines of the Bible. That’s obvious in our acceptance of the Book of Mormon and the claim of a continuing line of modern prophets and apostles — but also in explicit authoritative declarations from our apostles and prophets that the Founding Fathers, the Protestant Reformers, Confucius, Plato, Muhammad, and others received inspiration.

Our Evangelical Protestant brothers and sisters, on the “right,” share the high (literal) Latter-day Saint view of revelation, but restrict such revelation to the closed biblical canon — a restriction that Latter-day Saints manifestly reject. (Indeed, that’s one of the defining and most revolutionary principles of the Restoration.)

Hence, in my terminology, Latter-day Saints occupy a middle position between a general recognition of a defined-down prophethood, on the one hand, and, on the other, the restricted allowance of a robust view of prophethood. Latter-day Saints posit a spectrum of inspiration and recipients of inspiration, and readily grant that it continues beyond the boundaries of Mormonism.

(To be continued.)