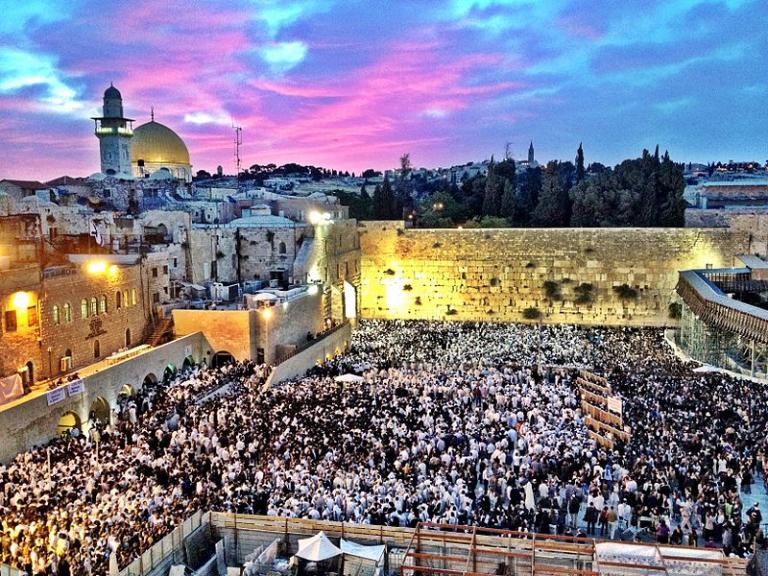

Another passage from one of The Manuscripts. This one deals with the changes that occurred in Judaism in the wake of the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and the cessation of prophecy among the Jews:

An example will serve to make the new situation clear: At roughly the time of Christ, a great Jewish thinker by the name of Philo Judaeus lived in Egyptian Alexandria. Philo was thoroughly at home in Greek literature and wrote excellent Greek himself. His attempts to harmonize Judaism with Platonic philosophy put him in the vanguard of the intellectual life of his day. (He is, in my opinion, a highly important figure for the understanding of the Great Apostasy, for he seems to have been the first to apply the tool of allegorical interpretation to the scriptures in order to ensure that they taught philosophy and that they never ever taught anything embarrassing, such as the doctrine of an embodied God.) By the middle of the second century A.D., however, a figure such as Philo would have been unthinkable within Judaism. And, indeed, it’s very striking that, while early Christian thinkers like Origen and Clement of Alexandria carried on the kind of allegorical reconciliation of scripture with Greek philosophy that had been Philo’s chief interest, he had no successors at all within Judaism itself. In fact, Judaism appears to a large extent to lack much of anything that can strictly be called “theology.” The Christians worked up doctrines like that of the “Trinity,” which proved fertile ground for heresies and disagreements, and what Paul Johnson calls “the professional Christian intelligentsia” became preoccupied with disputes over theology and dogma and have remained so down to the present day. The leading thinkers of Judaism, by contrast, were preoccupied with behavior, with the way life should be lived in this world. As Johnson puts it, “Judaism is not so much about doctrine—that is taken for granted—as behaviour; the code matters more than the creed.”[1] Indeed, although Christian theologians began producing creeds from quite an early period, the first Jewish creed was not composed until the Egyptian Jew Saadya Gaon, under influence from Greek philosophy, issued his ten articles of faith in the tenth century A.D. Jewish doctrine was relatively simple—God was one, for instance, not three-in-one-and-one-in-three—and didn’t call forth the kinds of disagreements that would divide Christendom into innumerable warring factions.

[1] P. Johnson, History of the Jews, 161, 162.

Posted from Chicago, Illinois