This item, written by Darvell Rowley (whom I do not know) reached me via a circuitous route on social media a few days ago. I hope that he won’t mind my sharing it; I’ve been unable to reach him. I’ve also borrowed some of the photographs that accompanied his comments.

I have some very sad news for those who remember Mr Clark, the greatest teacher ever at Mountain View High School, for all things Physics, Geology, Astronomy, and Environmental Science.

Eugene Clark and his wife had to return from their second LDS Mission early in March of this year, this one in Argentina, they found a tumor the size of a tennis ball in the middle of his brain. They left Argentina the next day, he was diagnosed with Stage 4 Terminal Glioblastoma (brain cancer).

Mr. Clark passed away yesterday afternoon, leaving the universe just slightly dimmer for the lack of his energy, his enthusiasm, his light.

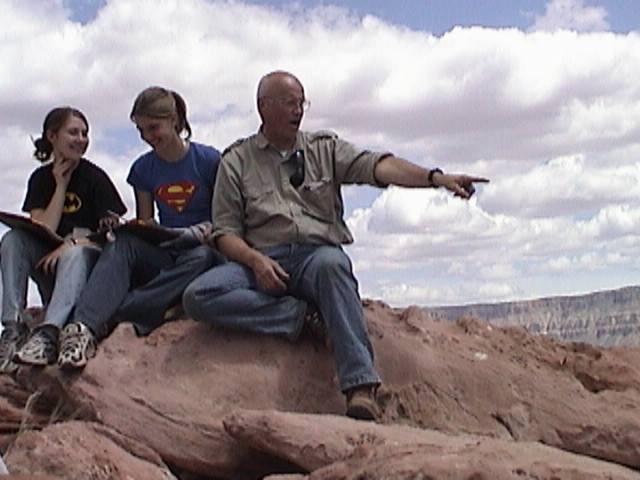

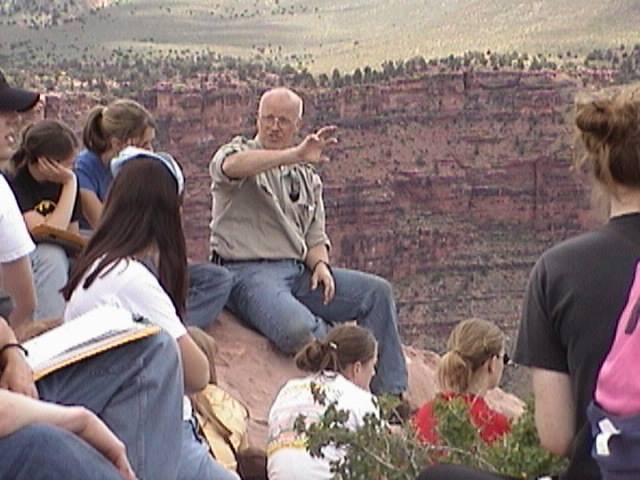

Mr. Clark was the most influential teacher I ever had. He taught me how to use my mind to think critically, view life from unbiased perspectives, take in all things around us as data, sort it, make sense of it. Even after graduation from high school, Mr Clark invited me and my friends, all former students, to go along on his annual Grand Canyon Geology Field Trip, as chaperones. He instilled within me a love for road tripping, planted in me the desire to travel, showed me how to plan properly, efficiently use the allotted time to see as much as possible, be aware of my surroundings. I was fortunate enough to have him invite me along on two separate trips to study volcanoes in Costa Rica, again as chaperone, despite the fact that I had gained a computer career and did not become the Geophysicist, Geological Engineer, or Astrophysicist I was absolutely certain I was going to become. He taught me how to continue to look at the land all around, to make sense of it, to notice fault lines, volcanic intrusions, conglomerate formations, talus piles, entrenched meanders, moraines, to attempt to identify all types of rock and understand how they got there. He took us all over the country in Costa Rica, saw both oceans, tried surfing at Jaco beach, fed crocodiles, experienced ziplines thru the cloud forests of Monteverde, hiked Vulcans Poas, Hirazu, Arenal, witnessed the magical beauty of hot springs of Tabacon. I can still vividly remember hiking thru the jungle in front of him, up the steep sides of an ancient volcano, holding onto roots and plants, jumping around, laughing, him telling us stories of the crazy hikes and rock climbing he did in his youth, mapping sections of the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, joking about his age and the struggles of the hike, despite successfully getting a couple dozen eager students and chaperones to the top of the volcano to view a crater filled with rain water. His countenance would immediately change, once again assuming the role of Teacher, and with unrivaled passion, exciting lectures would pour forth.

I think I can speak for everyone who ever had any of his classes, that we could all listen to Mr Clark speak for hours, so much knowledge and wisdom in his mind, never lacking a moment. I took all of his classes, every subject he offered, was even his teacher’s aide senior year despite that I had enough credits to not be there, I couldn’t get enough. He had an uncanny ability to make complicated dry subjects come to life, be fascinating, make sense, be clear. In a world of public education with underpaid teachers, Mr Clark was the diamond that out shined every other teacher without even trying to do so, a humble soul, his love for science radiated, inspired. I never met a student who didn’t enjoy his lectures. I am certain he was certainly beloved by all.

I was fortunate enough to stay in touch with him via email this last decade, eagerly awaiting for him to get off his mission February 2018 so that I could visit with him again, tell him of my travels, my wanderings, my journeys. I didn’t hear from him for quite some time, I wasn’t sure why the silence, it didn’t seem in character of him not to respond. Yesterday, his daughter reached out to me in morning with the bad news, Eugene Clark was quickly slipping from this world. I had no idea that he’d been fighting for his life these last 9 months.

It’s easy to live life and say “no regrets”, that being said I regret not getting to see him one last time, so much I wanted to say to him, so much I wanted to ask. Mr Clark, you are already missed, thank you so much for changing my life, for inspiring me. Rest in peace.

Now for my own commentary:

Unfortunately, I did not know Mr. Clark very well. But two of my sons were able to go with him on his remarkable field trips to Costa Rica — and I accompanied the second son’s group as one of its chaperones. (It was a spur-of-the-moment decision, urged on me by a friend and fellow parent who was going. My son was not pleased. It turned out that he had a secret girlfriend who was also in the group; he scarcely acknowledged my existence for the entire trip.)

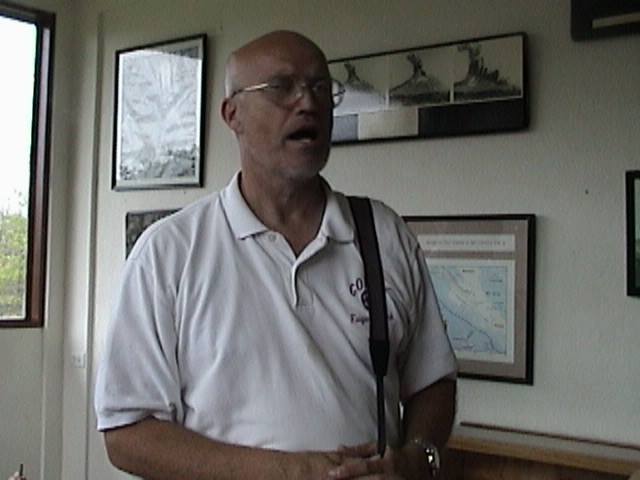

I had heard wonderful things about Gene Clark, but I was even more deeply impressed during our time in Costa Rica. Mr. Clark was one of the most remarkable people I’ve ever met. He was an accomplished geologist — actually, he was Dr. Clark, with a Ph.D. from the University of London — who already had a substantial career behind him, including serious academic publications, in private industry when he came to Mountain View High School following a downturn in oil prices and some sort of lay-off. His two principal geographical interests were, I believe, Oman and Costa Rica. Brigham Young University recruited him to teach several courses, but he found that he actually loved teaching high school students.

And he was phenomenal at it. I well recall recruiting my father-in-law, an exceptionally resourceful engineer, to help our eldest son build a melon-hurling catapult for one of Mr. Clark’s competitions. (I remember that catapult with special clarity because — long story — I broke a couple of ribs in connection with it.)

I think that it would be fair and accurate to say that my sons revered him.

A few of you may be aware of the old pulp fiction character Doc Savage, the incredibly brilliant, unbelievably strong crime-fighting forerunner to many subsequent superheroes. (Surely a film about him must be in development, somewhere?) As I watched Mr. Clark in Costa Rica, comparisons to Doc Savage kept coming to mind. He was, beyond question, extraordinarily intelligent and deeply versed not only in geology but other sciences. But he could also out-hike his students; he bicycled long distances every day to and from work. He seemed superhuman, omni-competent.

He told me one evening as we relaxed in a Costa Rican hot tub after a day of hiking (in an area that he had been studying for decades) that he had once dreamed of being a historian. But he found reading difficult, because he was dyslexic. He was, though, a genuine historian — of the natural landscape. He could read the geology of an area and explain its story, how it came to look the way it did, as well as, or better than, anybody I’ve ever encountered. It was a wonderful experience to listen to him.

He was also a man of faith and commitment. He had, I’m told, even been a stake president. Twice — once in London and once in Texas. And a Spanish-speaking mission early in his life had powerfully affected him in ways both spiritual and secular.

And he had been involved, to at least a slight degree, with the old Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (or FARMS) in its glory days. Here’s a passage from Warren P. Aston’s 2015 book Lehi and Sariah in Arabia: The Old World Setting of the Book of Mormon:

A 1995 visit to Oman by FARMS-sponsored geologist Eugene E. Clark had resulted in a FARMS Preliminary Report that gave an updated assessment of the geology of the Dhofar region, without any focus on the candidate areas for Nephi’s Bountiful. Clark’s paper noted the existence of minor iron deposits east of Salalah and that they were likely to be present in association with manganese and carbon. Such a combination would result in high-grade steel suitable for tools.

Perhaps my single favorite memory of Mr. Clark is of sitting with him while watching the continually erupting Mt. Arenal, in Costa Rica. We were staying at the Volcano Observatory on an adjacent ridge. He was taking notes, with a cassette player sitting next to him blaring out Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries. Perfect background music for a mad scientist.

He had already told me of trying to reach the summit of Mount Arenal some time before. He and his hiking companion, a Costa Rican botanist whom I had met, had finally abandoned the attempt when a basalt block about the size of a school bus had landed a few dozen yards from them. (The volcano was, at the time, spitting such blocks out about every two minutes or so.)

A question occurred to me:

“If the volcano were to explode right now, as you predict it will within the next few decades at most, what would happen to us?”

“We would be obliterated. Vaporized.”

“Would there be anything we could do?”

“Sure! We could run toward the top of the ridge, trying to get to the protection on the other side.”

“Would that help?”

“No. The pyroclastic flow would be coming toward us at about 100-150 miles per hour. But it might help us to feel a bit better during our last seconds of life.”

“Well,” I observed, “we must be pretty safe here right now. Otherwise, if they had reason to expect an imminent eruption, the staff of the Observatory would have abandoned the place.”

“Oh,” Mr. Clark responded. “You misunderstand. There’s no staff here. They’re not that crazy. This place is automated. The staff monitor the instruments from San Jose, about 150 miles away.”

Gene Clark was one of the most alive, most vivid, most energetic, and most interesting people I have ever encountered. The world is, indeed, dimmed and impoverished by his passing.

I’m reminded of a comment made by C. S. Lewis in a letter that he wrote roughly two weeks after the unexpected death of his friend (and fellow “Inkling”) Charles Williams:

Death has done nothing to my idea of him, but he has done – oh, I can’t say what – to my idea of death. It has made the next world much more real and palpable.

When death meets someone as vital and alive as Gene Clark, death seems somehow diminished. But so, unfortunately, does this mortal sphere. And so we mourn.