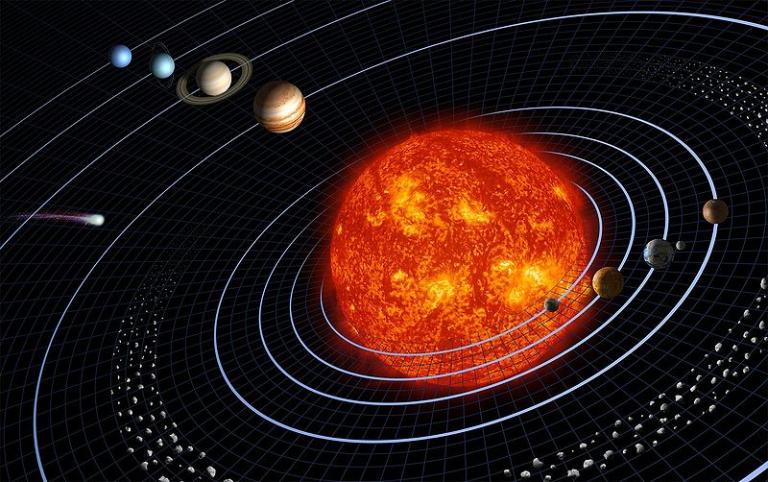

Not even remotely to scale, and without the dwarf planet Pluto.

It seems to have been Pythagoras, in the sixth century BC, who first used the term cosmos for the orderly and harmonious universe that we observe, as opposed to the chaos that it could be and might once have been. And, although little is known for certain about him, Pythagoras appears to have been the first, or among the first, to have seen that nature could be represented and discussed mathematically. One of his influential notions was that of the “music of the spheres” or the “harmony of the spheres.”

A beautiful statement of that notion appears in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, V.i.52-63, when Lorenzo speaks to his beloved Jessica:

Or, as the modern “Sparknotes” paraphrase has it,

How beautiful the moonlight’s shining on this bank! Let’s sit here and let the music fill our ears. Stillness and nighttime are perfect for beautiful music. Sit down, Jessica. Look at the stars, see how the floor of heaven is inlaid with small disks of bright gold. Stars and planets move in such perfect harmony that some believe you can hear music in their movement. If you believe this, even the smallest star sings like an angel in its motion. Souls have that same kind of harmony. But because we’re here on earth in our earthly bodies, we can’t hear it.

Having discussed Pythagoras on pages 266-267 of his book How It Began: A Time-Traveler’s Guide to the Universe (New York and London: W. W. Norton and Company, 2012), Chris Impey, University Distinguished Professor and Deputy Head of the Department of Astronomy at the University of Arizona, continues with a related discussion of the great early seventeenth-century German mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler:

Two thousand years later, Kepler applied Pythagoras’s ideas to the orbits in the Solar System. Kepler’s life was so difficult and chaotic we can imagine why he sought harmony in the celestial realm. He was sickly, myopic, and covered in boils. His father abandoned the family when Kepler was a teen, and his mother dabbled in the occult and was later put on trial as a witch. Greek geometers had discovered that only five solids can be constructed from regular geometric shapes: these perfect “Platonic” solids have 4, 6, 8, 12, or 20 sides. Kepler realized that these solids nested would give the relative spacing of the six planets known at the time. He was even more excited when he found that the ratios of maximum and minimum angular velocities of the planets corresponded to musical intervals. By combining pairs of planets he was able to derive the intervals of a complete scale. Kepler thought the music of the celestial realm manifested spiritual perfection that humans could only aspire to.

The resonance between mathematics and music was embodied more recently by Einstein, who was quoted as saying “Mozart’s music is so pure and beautiful that I see it as a reflection of the inner beauty of the universe.” A competent and passionate violinist, Einstein liked to improvise late at night while he ruminated on physics problems. We can imagine an unbroken connection in space-time from Pythagoras and his plucked string, through Kepler via Plato and Ptolemy, to the violin of Einstein.

We also hear echoes of the tradition of the Dreamtime, the aborigine creation story where the universe is sung into existence. Also in the modern tradition of cosmology, a series of harmonies brings forth the material world, providing the seeds for growing stars and galaxies.

There was a piper playing at the gates of dawn. (267)

I find myself unavoidably thinking, in this context, of Aslan’s singing Narnia into existence in The Magician’s Nephew:

“The Magician’s Nephew: Singing Creation Into Being”