(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

My wife and I spent a substantial portion of our day yesterday visiting the Civil War battlefield at Fredericksburg, perhaps the bloodiest single area, taken as a whole, of the entire conflict (and, thus, in the domestic history of the United States). There’s plenty of reason for sorrow in the history there, at the cruelties that humans have visited upon one another and, sometimes, at our sheer stupidity.

There are, however, some stories out of Fredericksburg that offer some comfort and encouragement. Most prominent among them, perhaps, is the story of Richard Rowland Kirkland, who was, at the time, serving as a sergeant in the Second South Carolina Volunteer Infantry.

Kirkland had already fought at the First Battle of Bull Run (or, in Confederate parlance, the First Battle of Manassas), as well as at Savage’s Station, Maryland Heights, and Antietam.

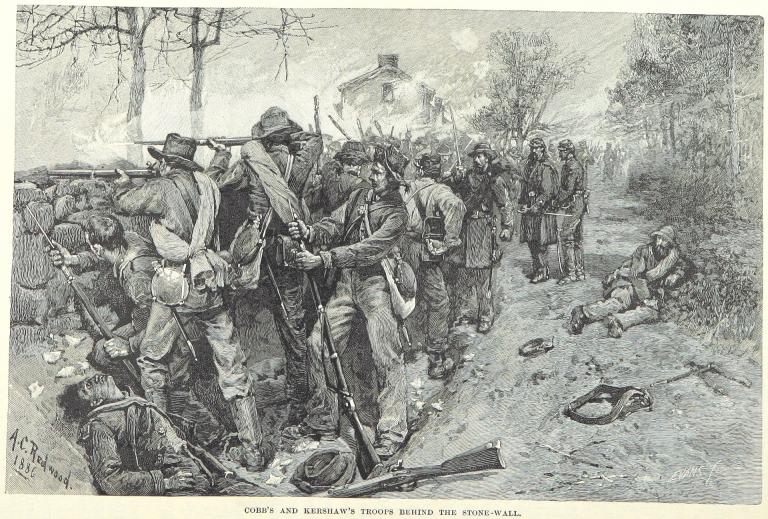

On 13 December 1862, the Second South Carolina Volunteer took up a position behind the stone wall that lined the Sunken Road at the base of Marye’s Heights, near Fredericksburg. In the action that followed, they inflicted heavy casualties on the Union troops charging against them. On the morning of December 14, it became apparent that over 8,000 Union soldiers had been shot before that stone wall at Marye’s Heights. Many of those remaining on the battlefield were still alive, but they were suffering terribly (and some very audibly) from their wounds and from thirst.

By far the most important source regarding Kirkland’s alleged actions that day is Confederate general J. B. Kershaw of South Carolina, Kirkland’s commanding officer during the battle. His account appears in a letter that he wrote on 2 January 1880 to the Charleston News and Courier, which is titled “Richard Kirkland, the humane hero of Fredericksburg.”

According to General Kershaw, Sergeant Kirkland approached him and said, very emotionally, “General, I can’t stand this.” When the general asked him what he meant, he replied: “All day I have heard those poor people crying for water and I can stand it no longer. I come to ask permission to go and give them water.”

Kershaw responded, “Kirkland, don’t you know that you would get a bullet through your head the moment you stepped over the wall?”

After some back and forth between the two, General Kershaw overcame his reluctance and permitted Sergeant Kirkland to go.

Armed with all of the water-filled canteens he could carry, the young Confederate soldier crossed the wall and, under a shower of bullets, provided water to the nearest victim he could reach, helped him into a more comfortable position, and left him a canteen. At this point, his purpose now being understood, the Union troops withheld their fire, and for an hour and a half, he went from from wounded man to wounded man while his comrades filled canteens for him. (According to General Kershaw, they were prevented from actually joining him out on the battlefield by orders against their crossing the line.)

Richard Rowland Kirkland went on to fight at Chancellorsville and then at Gettysburg where, according to his commanding officer, General Kershaw, he was promoted (for “conspicuous gallantry”) to the rank of lieutenant. On 20 September 1863, he was fatally shot during the Battle of Chickamauga. He was just twenty years old. It is said that his last words were “I’m done for . . . Save yourselves, and please tell my Pa I died right.”

“I doubt not,” wrote General Kershaw, “that he wears now a bright crown bestowed by Him who promises that a cup of cold water given in the right spirit shall not lose its reward.”

In hearing the legendary story of Sergeant Kirkland, one naturally thinks of the remarkable story of Desmond Doss, recently told in Mel Gibson’s remarkable film Hacksaw Ridge.

It must be said, however, that some have cast serious doubt upon General Kershaw’s story of Richard Rowland Kirkland, which only appeared nearly three decades after the Battle of Fredericksburg. See, for example, “Is the Richard Kirkland Story True?” (However, see, too, the often rather spirited comments that follow Michael Schaffner’s critique.)

Whatever one may think of the specific details regarding Sergeant Kirkland at Fredericksburg, J. B. Kershaw’s letter speaks very powerfully to what, amidst all the evils and sorrows of this fallen world, we desire to be and what we hope and wish to be ultimately true.

Posted from Richmond, Virginia

P.S. In the context of this discussion of such folks as Desmond Doss and Richard Kirkland, I need to pass on an important communication from one of my anonymous email correspondents. This particular writer participates on a predominantly ex-Mormon atheistic message board belonging to a certain “Dr. Shades.” For reasons best known to the secretive fellow, he often likes to share his deepest thoughts with me and to express his feelings about . . . well, about me. (He’s done so frequently for a number of years now.) Thus far this week, he’s offered two comments. One of them, alas, contains language that I don’t permit on this blog. The other, though, is marginally acceptable, and I think his insights deserve to be shared. Here’s his message: “pimpin plumper. garrulous gobbler. lyin lardass.”