My father was born 105 years ago, today.

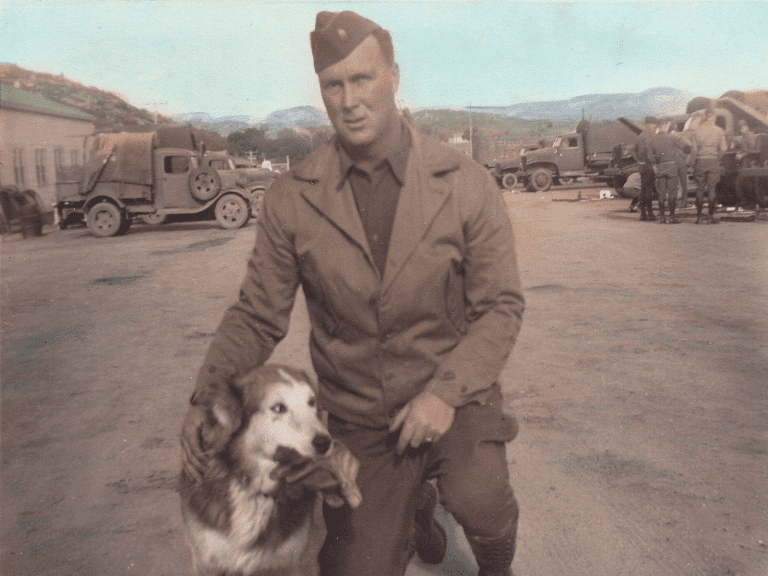

He came relatively late to marriage and to fatherhood. The Great Depression, working with Franklin Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, enlistment in the peacetime United States Army, the outbreak of World War Two, and then time spent trying to earn a living and eventually to establish a construction business in booming postwar southern California — these all interfered with any sort of romantic life.

He once told me that he finally decided that he needed to find a wife and start a family because he was afraid that he was getting “weird.” He had spent far too much time in all-male environments — in the CCC, in the Cavalry (believe it or not, there was still an Army horse cavalry in the 1930s), on various military bases, in Army German classes at the University of Chicago, in training at Maryland’s famous Camp Ritchie, at war in the European theater, with California construction workers. He had been too long removed from polite society and the social graces. He was, he thought, developing some off-putting habits, becoming (for example) much too sloppy about the way he acted and dressed, and his sisters were worried about him.

Eventually, he married a widow who had a son — my brother — and, with her, he himself had a boy. He raised Kenneth and me, though, as if we were both his biological sons. To his enormous credit, we never sensed any difference in his treatment of us, and I always thought of my beloved half-brother, very nearly ten years my senior, as fully and in every way my brother. (How I miss them both!)

I think of my father every single day. Literally. I said at his funeral that I would, and, perhaps even somewhat to my own surprise, I really do. Certain things always remind me of him. And not necessarily the obvious things that might be expected to do so.

Today, for some reason, I’ve been thinking of his reaction to returning from wartime Europe. He had seen horrible things. After eluding German U-boats during an Atlantic crossing, he had been stationed near London, and he was often actually in the city (whereby hangs a tale for another time), during the period when the German V-1 “buzz bombs” and the newer V-2 supersonic rockets were raining death, terror, and destruction upon it. He never saw London with its lights on. The city was always blacked out. (One of my regrets is that I never got him back to London to see the city illuminated and alive at night.) Then, shortly after the D-Day invasion, assigned as a staff sergeant to the Eleventh Armored Division of General George S. Patton’s Third Army, he was over on the Continent, passing through Bastogne, Belgium, not too very long past the Battle of the Bulge. He was involved in the crossing of the Rhine River and then — he never forgot the horror of it — in the liberation of the Nazi death camp at Mauthausen, Austria. By the end of the European war, he was in Le Vésinet, a suburb of Paris, where he awaited demobilization and return to the United States. (Owing to a relative’s wartime mismanagement, the family farm in North Dakota had been lost by that time, his parents were looking for a place to go, and he had no real home to which he could return.)

I remember his reaction, as he described it to me, to what he found back in the United States. After the terrible sights that he had seen, he arrived to find people arguing over, and cheating over, coupons for butter and for sugar. The incredible triviality and pettiness of such things appalled him. I recall once, even many years later when I was a fairly young boy, his reaction to a conversation with a new neighbor. For some reason, the man was telling us about how he had spent the war: Avoiding military service, he had worked in a factory where tanks were manufactured. His job was to put rivets into their undercarriages. He wore ear plugs of some sort, though, and he found that he could simply sleep while the nearly-assembled tanks passed over his head. “Many young American men died,” my father replied, “because their tanks were poorly made.” And he turned on his heel and walked away, with me close behind. When he finally slowed down, he was nearly speechless with indignation.

I wonder what he would make of today’s toxic public discourse, where we delight in eviscerating and demonizing each other — not only about politics and religion but even about such inconsequential trivia as sports. I doubt that he would be positively impressed. There are, he knew, vitally important things. But most things don’t matter much.