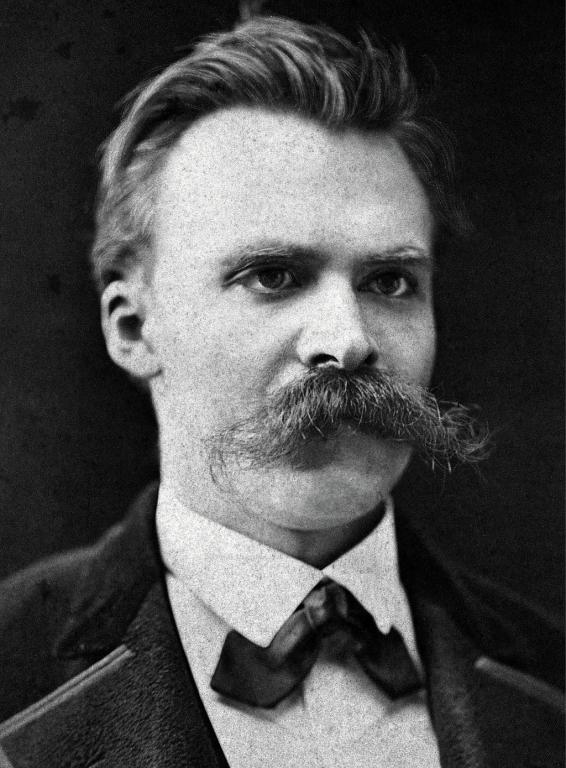

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

A couple of passages from Friedrich Nietzsche, The Antichrist: A Criticism of Christianity [1888], translated by Anthony M. Ludovici (New York: Barnes and Noble, 2006). But, first, a few lines from Dennis Sweet’s introduction to this edition:

In earlier books Nietzsche had made that most profound announcement: “God is dead.” In other words, there are no absolute, unconditional, or objective values in the world. Whatever meanings that exist in life are put there by us, by human beings, by “value-creators.” (vii)

Now to Nietzsche himself:

What is good? All that enhances the feeling of power, the Will to Power, and power itself in man. What is bad? — All that proceeds from weakness. What is happiness? — The feeling that power is increasing — that resistance has been overcome.

Not contentment, but more power; not peace at any price, but war; not virtue, but efficiency [not quite the right translation, in my view, of Tüchtigkeit, but it will serve] (virtue in the Renaissance sense, virtù, free from all moralic acid). The weak and the botched shall perish: first principle of our humanity. And they ought even to be helped to perish.

What is more harmful than any vice? — Practical sympathy with all the botched and the weak — Christianity. (Section 2, page 4)

Although I think that Nietzsche would have found Nazism and the Nazis repulsive and contemptible, it’s not difficult to see why they were attracted to at least some of what he said.

Plainly, too, he had come heavily under the influence of Darwinism:

Christianity is called the religion of pity. — Pity is opposed to the tonic passions which enhance the energy of the feeling of life: its action is depressing. A man loses power when he pities. By means of pity the drain on strength which suffering itself already introduces into the world is multiplied a thousandfold. Through pity, suffering itself becomes infectious; in certain circumstances it may lead to a total loss of life and vital energy. . . . On the whole, pity thwarts the law of development which is the law of selection. It preserves that which is ripe for death, it fights in favor of the disinherited and the condemned of life; thanks to the multitude of abortions [perhaps better, “misfits”?] of all kinds which it maintains in life, it lends life itself a sombre and questionable aspect. People have dared to call pity a virtue (– in every noble culture it is considered as a weakness –); people went still further, they exalted it to the virtue, the root and origin of all virtues. (Section 7, page 6)

My question, to those who believe that “God is dead” (or, less literarily, that God never existed) and that, accordingly, there are no absolute, unconditional, or objective values in the world and that whatever meanings that exist in life are put there by us, by human beings, by “value-creators,” is this:

You may well find Nietzsche’s moral stance, above, distasteful. I certainly do. But is it “wrong”? Can anything, in a world where there are no objective or absolute values, actually be said to be “wrong”? And, if you believe that it can be, how would you demonstrate to someone agreeing with Nietzsche that he or she is “wrong”?