It’s time to revisit my occasional commentary on the New Testament. I’ll take it slowly and in small snippets, and I plan to go through all four gospels and the book of Acts.

I won’t be doing the gospels one by one, but, rather, in “harmony,” using as the basis for my divisions of material Kurt Aland, ed., Synopsis of the Four Gospels: Greek-English Edition of the Synopsis Quattuor Evangeliorum, 14th ed. (Stuttgart: German Bible Society, 2009). The numbers in the titles of my posts in this series will refer to the sections of that publication.

I’ll make no pretense of completeness. I don’t have anything remotely like the time that a full commentary would require. I’ll simply pick up something of interest in each section, hoping that at least some out there will find what I have to say of interest or of use.

So now I begin:

Matthew begins fairly abruptly, announcing that it will give the genealogy of Jesus.

Mark announces “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” — providing the first Christian occurrence of that important word gospel. Or, more properly, of the Greek word euangelion [εὐαγγέλιον] — which is the source of such English words as evangelist and evangelical.

Gospel, of course, is a modern English rendering of the Old English god-spell, or “good news,” which is a calque (a literal, word-for-word translation) of the Greek εὐαγγέλιον, which also means “good news.” Eu- is a Greek prefix signifying “good” — think of English words such as euphoria (from the Greek phero, “to bear”), eulogy (good speech), euphemism (good saying), eugenics (good birth), and euthanasia (good death) — while the -angelion comes from the Greek equivalent of English “message” or “news,” as does the word angel (“messenger”).

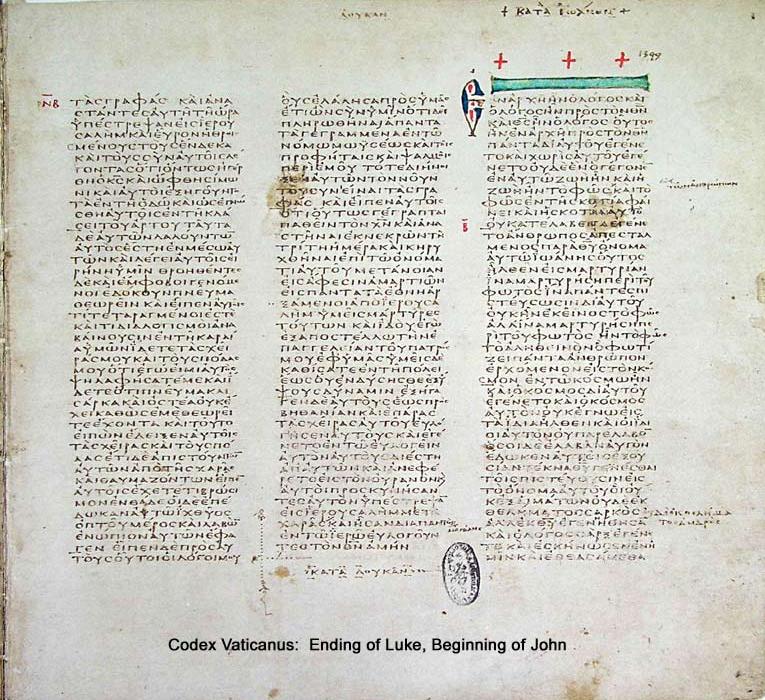

Luke begins with a rather academic-sounding prologue or preface, signifying serious historical intent and method with its reference to “eyewitnesses” (autoptai, literally something like “own eyes”). This is very important. The author of Luke was, plainly, well educated, and the gospel of Luke is written in the manner of ancient Greek historiography. (For a brief review, by Noel Reynolds, of an extraordinarily interesting book on “eyewitnesses” and the four gospels, see this item in the more-or-less suppressed real first issue of the Mormon Studies Review.)

Finally, entire books could be written (and have been written) on the prologue to John’s gospel. I’ll content myself here with observing that John 1:1-14 can be read as a kind of Christmas or Nativity story. Around the time of Jesus and John, Jewish thinkers (notably Philo of Alexandria) were using the term logos (“word”) to describe an intermediary between humans and the Most High God. That’s also the term used in John 1:1, though its meaning is far richer than the English word suggests. It can mean reason, speech, logic, rationality, cosmic order, discussion or council, and many other things besides. At Faust 1.1.889, in fact, the German poet J. W. von Goethe famously translated it as Tat (or, in English, deed).

For more than 2,000 years, the Christian message has been that, in Jesus, this divine intermediary came to Earth and dwelt among us.

There. That’s a bit longer than I typically intend to go on. But it’s a beginning.