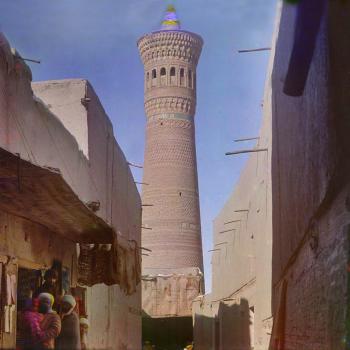

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

My friend Bill Hamblin and I published this article in the Deseret News back on 9 August 2013:

The Middle East has faced an abundance of conflicts, rival groups and, for many Americans, difficult names. It’s often hard to tell the players without a scorecard. Here, as a possible aid to understanding the background behind the headlines, is a brief primer on two of those organizations, Hezbollah and Hamas. The first of these — the “Hizb Allah” or “Party of God,” whose name is properly pronounced with emphasis on the last syllable — is a radical Shi‘ite Muslim group that was formed in reaction to the Israeli invasion and occupation of southern Lebanon in 1982. Not surprisingly, it’s strongly anti-Western and anti-Israeli.

Although it’s quite capable of acting on its own initiative, Hezbollah, being Shi‘ite in an overwhelmingly Sunni neighborhood, is closely allied with, and has often apparently been directed by, the Shi‘ite government of the Islamic Republic of Iran. As a proxy in Iran’s campaign against Israel and the West, it has received substantial financial assistance, training, weapons and explosives and political, diplomatic and organizational aid from Tehran and, at least before Syria’s current troubles, from Tehran’s allies in Damascus.

Hezbollah is known to have been involved in numerous anti-U.S. terrorist attacks and was notorious in the West for its seizure of Americans and other hostages during the decade of 1982-1992. It’s viewed by most local Lebanese Shi’ites, however, as the only effective organization to have offered resistance to rival Lebanese groups during the Lebanese civil war, and against U.S., Syrian and Israeli attacks and oppression.

Hezbollah has its base in the Bekaa Valley slightly less than 20 miles to the east of Beirut, in the southern suburbs of the city itself, and in southern Lebanon, but it has established cells in Europe, Africa, South America, North America and Asia. In recent years, it has become a significant military and political force within Lebanon, including representation in Parliament. Its status was considerably enhanced by its stout resistance to Israel during the 2006 Lebanon War.

Hamas — or, perhaps more properly, HAMAS, since its name, which plays off the Arabic word “hamasa” (“valor,” “courage”), is an acronym from the Arabic of its official title, “Islamic Resistance Movement” — is a Sunni organization that emerged from the Muslim Brotherhood during the first Palestinian “intifada” or “uprising” against Israel in 1987. (Emphasis, again, should be placed on the last syllable of the name.) It has become the primary anti-Israeli religious opposition in the occupied territories, with centers of strength in the West Bank and with dominant popularly elected political power in the Gaza Strip.

Hamas is rather loosely organized, but is mainly known to Americans for the volleys of rockets that it sends into southern Israel and for its use of suicide bombers, which it pioneered along with the non-Muslim “Tamil Tigers” or “Liberation Tigers” of Sri Lanka. While it condemns American policies favoring Israel, it has not targeted the U.S. directly. Instead, it focuses on attacking Israel itself, whose right to exist it has adamantly refused to recognize.

Hamas is willing to agree to occasional truces, but won’t sign a peace treaty with the Jewish state. In this respect, it maintains a more overtly radical position than does Fatah, the largest faction of the more secular Palestine Liberation Organization or PLO, which dominates the West Bank area and is much more open to negotiations with Israel.

Hezbollah and Hamas (along with the Muslim Brotherhood itself in Egypt) have garnered a great deal of popular support through their willingness and ability to provide social services to the poor — hospitals, welfare, educational facilities, free clinics and clean water, for example — in places where governments have long been corrupt and ineffective while, at the same time, autocratic and oppressive. In effect, they’ve filled vacuums of social and economic services that badly needed filling.

Tyrants throughout the Middle East — most recently Bashar al-Asad of Syria — have ruthlessly suppressed political opposition but have been generally unwilling to suppress Islam. This has left resistance to Middle Eastern dictators largely in the hands of Muslim religious movements. The rise of Islamic fundamentalism over the past three decades rests on many factors, but the fecklessness of secular institutions and ideologies across the Muslim world, including the lack of freedom and of vibrant, open markets and opportunities for socio-economic advancement, ranks prominently among those factors. In a sense, today’s Islamic extremism represents the unpaid socio-political bills of modern Muslim states, which have gravely failed their citizens.