It’s difficult to overstate the historical and cultural importance of the place where I’m sitting at this very moment. For one thing, Samarkand is located on what has come to be called, quite famously, the “Silk Road.” The term was originally coined in German, in the nineteenth century, as die Seidenstraße. It entered English and other languages not long thereafter, although some prefer nowadays to term it — a little less attractively, I think — the “Silk Routes.” Why? Because it’s actually not a single road, but a fairly broad assembly of related trade routes. Moreover, few merchants or travelers covered the entire distance, the whole route. Rather, there were lots of middlemen, operating as it were in “relays.”

With that proviso, though, I think that I’ll nonetheless refer to it here as a single entity.

The Silk Road flourished from roughly the second century before Christ until the middle of the fifteenth century. It extended for approximately 4,000 miles (or 6,400 kilometers).

In the West, trade routes joined it from both the north and the south at Palmyra (or Tadmor), in what is today Syria. Depending upon your point of view, depending (in other words) upon which direction goods and people were traveling, I suppose these could be seen as either as tributary roots or as diverging branches.

The northern routes were coming down from Aleppo and, beyond Aleppo, from Constantinople (or, at the end of its story, from Istanbul, which was simply Constantinople after its conquest and renaming by the Turkish Ottoman Empire under Sultan Mehmet II, “the Conqueror”). And Europe, too — especially and most obviously southern Europe — profited indirectly from these pathways of trade.

From the south, the feeder or delivery routes were coming up from Damascus and, beyond Damascus, up from Cairo. And, of course, trade and movement extended on across North Africa and down into East Africa.

At its eastern end, the Silk Route fed and was fed by end stations at Beijing and Huangzhou. The subordinate routes to those cities diverged or came together — again, depending upon the direction in which you were traveling — at what is today called Xi’an but was anciently known as Chang’an.

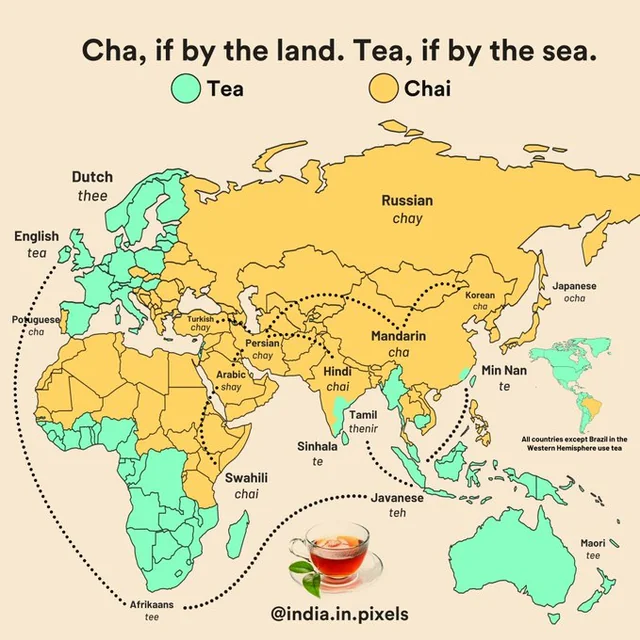

The Silk Road obviously facilitated trade and economic exchanges between East and West. For example, silk textiles from China were widely sought in Rome, Egypt, Greece, and elsewhere. (Hence, obviously, the name Seidenstraße or “Silk Road.”) But the East also provided such treasured goods as porcelain, tea, dyes, and perfumes. The word tea will serve excellently as an illustration. It is almost universal, with its close cognates, in every language on the planet. There may be exceptions, but I’m unaware of any. Consider this list:

- Spanish: el te

- French: le the

- German: der Tee

- Italian: te

- Portuguese: cha

- Dutch: thee

- Danish: te

- Swedish: te

- Finnish: tee

- Norwegian: te

- Icelandic: te

- Russian: chai

- Greek: tsai

- Japanese: ocha

- Korean: cha

- Chinese (Mandarin): cha (make sure you pronounce the “a” in a rising tone

- Thai: chah

- Hindi: cha

- Arabic: chai or shai

- Armenian: te

- Turkish: cay

- Croatian: caj

- Czech: caj

- Hungarian: tea

- Polish: herbata (notę the final syllable)

- Romanian: ceai

- Ukranian: chaj

- Hebrew: teh

- Somali: shaah

- Zulu: itiye

- Filipino: tsaa

- Vietnamese: tra

- Indonesian: teh

- Chinese (Cantonese): cha

- Sinhalese: the

- Tamil: tea

And all of these cognate words originate, ultimately, in a form of Chinese — that is, in China.

In exchange for silk and tea and dyes and perfumes and porcelain, regions at the western end of the Silk Road offered such valued commodities as horses, camels, honey, wine, and gold.

Of course, non-economic exchanges also occurred along the Silk Road. Cultural, political, and religious ideas traveled back and forth along its busy trade routes.

It’s difficult to know exactly how to categorize the transfer of Chinese paper making to the early Islamic world and then on to Europe. (That transfer seems to have happened somewhere near Samarkand. At the very least, near or within what is today Uzbekistan.) The transmission of Chinese paper-making technology was an economic transfer, of course, but, by making the production of books much less expensive than it had previously been, the arrival of paper in the Middle East and then in Europe fostered a cultural revolution that, furthered centuries later by Gutenberg’s application of movable type, transformed the Western world. (Among other things, it enabled the Lutheran Reformation, which rode to a remarkable degree upon Martin Luther’s talents as a popular pamphleteer and, obviously, upon the availability for the first time of relatively affordable Bibles.)

There is a lesson to be learned here, I think, about the venerable age of global markets and the enormous importance of international trade — and the interconnectedness of global civilizations. Having studied history all of my life, I am unrepentantly and inescapably a “globalist.” Civilizations don’t flourish in isolation. They never have. But far be it from me to mention any such lesson in a time when many people appear to imagine that prosperity is somehow magically created by erecting trade barriers.

Admittedly, not everything that traveled over the Silk Road was unequivocally positive — so there’s definitely a case to be made for at least some guidelines and controls. Gunpowder came from China, for instance. It eventually empowered the Ottomans (in Western Asia) and the Safavids (in Persia, or the vicinity of modern Iran) and the Mughals of India to gobble up the fragmented smaller states of the Islamic Middle Periods and to create in the islamic world what the late, great Marshall G. S. Hodgson aptly called the “Age of the Gunpowder Empires.” In Europe, the arrival of gunpowder put an end to the usefulness of castles and to the chivalry of gallant knighthood and, if anything, made wars effortlessly even more terrible and far more destructive than they had been before.

And then there’s the Black Death. That infamous bubonic plague pandemic that raged across Europe from AD 1346 to 1353 may have killed as many as fifty (50) million people — which is to say, perhaps fifty to sixty percent of Europe’s population in the fourteenth century. Where did it come from? It may have started in China or Central Asia and reached first the Middle East and then Europe via the Silk Road.

More to come, in sha’a Allah.

Posted from Samarkand, Uzbekistan