For specific reasons, I’m reposting this blog entry, which first appeared here on 11 October 2018:

There were times, particularly in my early graduate school days, when I thought that my having come from a completely non-academic family had worked against me.

I have friends and colleagues, themselves with strong Ph.D.s from prestigious schools, who have fathers and grandfathers and multiple siblings with professional and academic doctorates — in at least a couple of cases, with more than one doctorate — and for them, I discovered, going into a doctoral program was just something you did. No big deal. Practically everybody in their families had a Ph.D., an M.D., a D.D.S., a J.D., a D.Phil, an Sc.D, or, at least, a master’s degree.

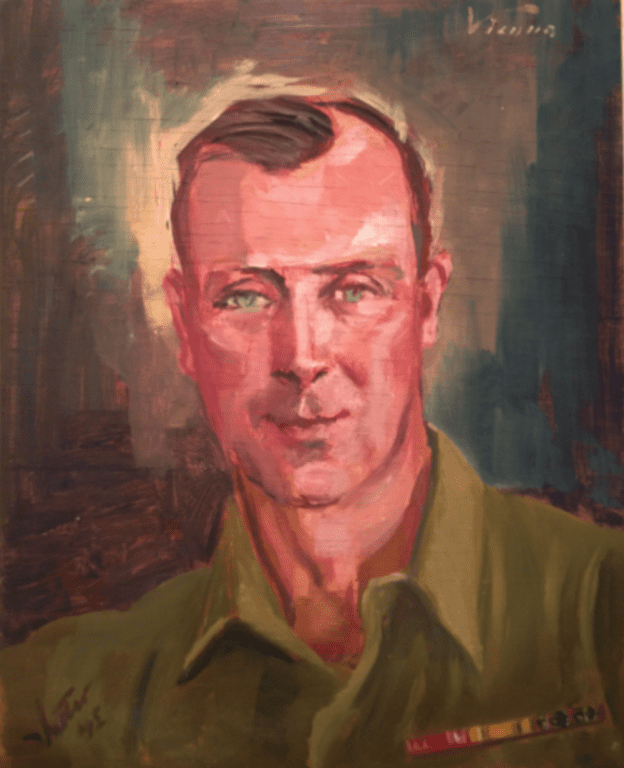

My family was not like that. My mother graduated from high school but never attended college. My father, caught up in the Great Depression, construction work in southern California, then Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, followed by the pre-war Army, and then, for the duration of the Second World War, living on various military bases pending deployment to England and later, having been assigned to General Patton’s Third Army, as a non-commissioned officer in France, Belgium, Germany, and Austria. He had managed a couple of years of part-time study at a forestry school in North Dakota and at Pierce College, in Los Angeles. When he was demobilized, he came out to California and eventually started a construction business of his own.

My parents weren’t unintelligent, by any means. Quite the contrary, in fact. (A sign of this is that the Army sent my father to the University of Chicago to study German, as well as to Maryland’s famous Camp Ritchie.) But my mother came from a small town in Utah and my father grew up on a farm located quite a distance outside an even smaller town in North Dakota, they hadn’t had the time or the leisure to obtain the kind of education that I was ultimately able to get, and they certainly couldn’t be described as “intellectuals.”

Given that background, going for a doctorate was uncharted territory for me. Nobody that I knew very well, certainly no one to whom I was related, had ever done such a thing. (My brother and I were about the only people that I knew of in the family up through our generation who earned bachelor’s degrees.)

But I’ve come more and more to appreciate a powerful benefit that my background conferred upon me: I worked construction just about every summer when I was in the United States, from high school through graduate school. (That was one of the reasons I chose to attend UCLA for my doctorate: It had, and has, a superb program in Near Eastern studies, but I could also work summers at the family business — of which, by then, my brother had assumed control.) I can’t say that I always enjoyed the work, but I really liked the men with whom I worked and whom I had known since I was a small boy — men like Tino Beltran and his brother Frank, and Joe Esparza,and our company mechanic, Red Faler (about whom I’ve written here on this blog).

One of the men who sometimes worked for our company was actually a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (I won’t name him because I don’t want to risk embarrassing his family, whom I knew.) He wasn’t a well-educated man. His grammar was poor, and I’ve sometimes joked, in recalling him to my wife and kids, that he had no idea at all where to locate 2 Nephi in the Old Testament. But even as a rather young boy, I noticed that he was the first to arrive at service projects and the last to leave, and that he was at every single one in which I ever participated. If there was a widow’s house to be fixed, he was there. Sometimes I was, too, but I had little to offer. I realized then that, while he was far from sophisticated or urbane, and while I aspired in those days to be at least somewhat more sophisticated and urbane than I was, he was worth at least two of me. I was convinced then, and I’m convinced now, that he will occupy a wonderful place in the celestial kingdom. Me, though? Well, I can hope.

I have many faults, but there’s one that I’m very grateful to have avoided: the arrogant elitism that sometimes afflicts academics. I just don’t feel it. I never have.

I can readily imagine that things might have been different for me. I have enormous respect for academia and my feelings for great colleges and universities border on religious awe. When I’m at Oxford or Cambridge or Caltech or Harvard, I feel almost as if I’m on holy ground. (“Behold,” said a friend and colleague as we stood one day by the statue of John Harvard in Harvard Square, “the omphalos tes ges [the navel of the earth]!” And — may I be forgiven for it! — I actually felt that way, just a bit.) Wherever I travel, if there’s a good school nearby I always try to visit it. I might very, very easily have become an academic snob.

However, having spent many of my formative years around manual laborers whom I considered friends and almost family — it took me a long time, as a child, to realize that my Uncle Warren at the construction company wasn’t even really a relative at all — and belonging to an extended family replete with farmers and truck drivers, construction workers and welders, I have never been even remotely tempted to regard academics as a superior breed. Being a professor is an honorable trade, of course, but no more so than being a cement finisher or a dry land wheat farmer.

This is on my mind because of some complacently elitist comments that I’ve recently observed from certain former Latter-day Saint academics who, I’m guessing, were not as lucky in this respect as I have been. They’re disdainful of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, of course, and regularly sneer at its claims and its doctrine. But what has really appalled me, I confess, is the sheer contempt that I’ve seen in them for ordinary members of the Church, whom they dismiss as rubes, fools, primitive bigots, uneducated and unreflective lowbrows, and, as one of them recently described Latter-day Saint temple-goers, as “philistines.”

Not that I have anything against any particular member of the faculty at Harvard but, on balance, I’ve always resonated to this 1963 statement from the Ivy-educated patrician William F. Buckley Jr.: “I should sooner live in a society governed by the first two thousand names in the Boston telephone directory than in a society governed by the two thousand faculty members of Harvard University.”

I simply can’t abide smug assumptions of class superiority. Much as I admire academic achievement and deep culture, I cannot see that such things make those who possess them better people or more valuable souls, let alone more pleasant to be around.

Posted from Las Vegas, Nevada