Here’s an article that I published in the Deseret News way back on 29 April 2010:

China is, by a margin of nearly 200 million, the most populous country on earth. And it appears, at least, to be a rising economic superpower. (According to The Economist, it averaged 15.1 percent annual growth in real GDP between 1997 and 2007, by far the highest rate of any major nation.) Fortified by its increasing wealth, China is integrating itself into the global economy and is modernizing rapidly, in all respects.

Important social theorists such as Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Max Weber and Émile Durkheim predicted in the 19th and early 20th centuries that religious belief and practice would decline as society modernized. This is the so-called “secularization thesis,” and contemporary China is a pretty good laboratory in which to evaluate whether their prediction was accurate.

Christianity seems first to have entered China when believers (perhaps, but not certainly, of a Nestorian type) reached Xian, the capital of the Tang Dynasty, in 635 and were permitted to establish places of worship and to proselytize. Mongol Nestorians were influential in the 13th-century Yuan Dynasty, and Franciscan friars from Europe arrived in 1289. However, in the latter portion of the 14th century, the Ming Dynasty set out to cleanse China of all foreign influences, including not only Christianity but Buddhism. Although St. Francis Xavier never reached the mainland, Jesuit missionaries (including the celebrated Matteo Ricci) arrived in the late 16th century, and Protestant missionaries came in the 19th century. (Chinese Protestants often describe them as the first Christian missionaries, period, frequently refusing to recognize Catholics as fellow Christians.) Then, however, the Communists took power in 1949, and, in what has been termed a “reluctant exodus,” foreign missionaries left. Worse still, during the 1966-1976 “Cultural Revolution,” religious practice was effectively banned.

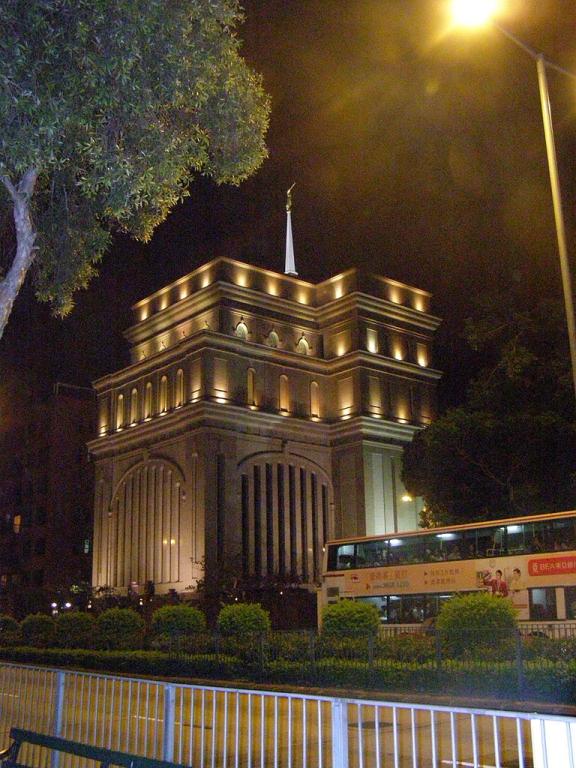

Now, though, China may be witnessing the biggest surge of Christianity in history. The Chinese government’s own statistics put the number of Chinese Christians at 21 million in 2006, up fully 50 percent from only 14 million in 1997. These Christians are affiliated with 4,600 Catholic churches and with approximately 55,000 official Protestant congregations. But the government figures are probably far too low. There is an underground Catholic Church that is almost certainly larger than the official one, and the government refuses to recognize thousands of Protestant “house churches.” A fairly conservative estimate is that China’s population includes at least 65 million Protestants and 12 million Catholics — slightly more Christian believers than there are members of the Chinese Communist Party. And some observers claim that Christianity in China has as many as 130 million adherents.

Official government statistics put the number of Muslims in China at roughly 20 million, mostly concentrated in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the country’s northwest. As with the Christians, though, this is probably a considerable understatement. But even the government figure puts China only a few million Muslims behind Saudi Arabia, the homeland of Islam, and there is strong reason to think that Chinese Muslims are surging, too, both in numbers and in commitment to their faith.

The more established traditions of Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism — often somewhat jumbled together, mixed with ancestor veneration and folklore — also enjoy a more public presence in today’s China than they have for several decades previously. Buddhist temples dot the countryside, large Buddhist festivals are increasingly tolerated, and a significant Tibetan Buddhist shrine — no less! — sits in the heart of the capital city, Beijing. The official state news agency says that there are approximately 100 million Chinese Buddhists

According to a survey conducted by the Pew Global Attitudes Project in 2006, 31 percent of today’s Chinese say that religion is very important or somewhat important in their lives. (Another survey put the percentage at nearly twice that.) By comparison, only 11 percent of the population, in this country that has been officially atheistic since the Communist Party gained control of it, says that religion is not important at all.

The flourishing of religion in China today provides little or no support for the so-called secularization thesis. And when we factor into our analysis the brutal repression to which religious believers were subject under the totalitarian rule of Chairman Mao, the persistence and even rebirth of religious faith in China is more remarkable still.

For a somewhat more recent and longer discussion, see Louis C. Midgley, “Christian Faith in Contemporary China,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 2 (2012): 35-39.

Posted from Richmond, Virginia