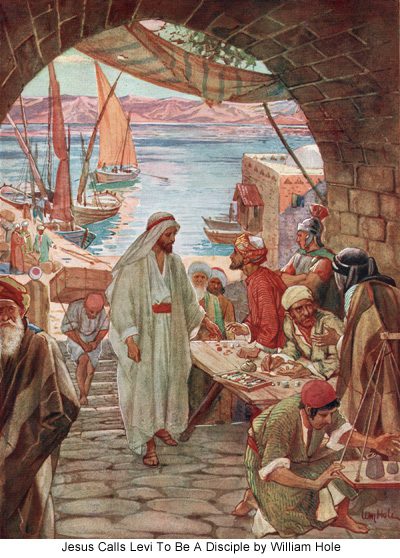

This account, of the calling of Levi or Matthew, provides one of our clearest glimpses into the character of Jesus. And it’s a very impressive one.

Levi or Matthew is himself a tax collector — not the most highly esteemed profession then or now, perhaps, but infinitely worse then. And Jesus is portrayed as dining with a whole group of “tax collectors and sinners.”

When he’s rebuked for the society he keeps, though, he points out that, as a physician of souls, he necessarily goes to those who are sick, not to those who are well.

But well, of course, may be ironic here. In fact, it probably is. For, while the sins of the “sinners” are obvious — and let’s not fall into the error of simply calling them “sins” within square quotes; they’re not imaginary, and neither Jesus nor the gospel writers were relativists — the sins of the “righteous” in this story are no less real. They’re just less easily apparent. Self-righteousness is plainly among them, as are arrogant self-satisfaction, a distinct lack of charity, and a sense of self-reliance rather than dependence on God.

***

Compare Matthew 9:14-17 and John 3:29-30

Jesus’ identification of himself as the “bridegroom” in these passages is an interesting one.

The relationship between God and his people is often portrayed in the Old Testament as analogous to a marriage in which God is the husband and Israel is the (often unfaithful) wife. See, for example, Jeremiah 3:1-14, Jeremiah 3:20, and Jeremiah 31:31-33. And, of course, the little prophetic book of Hosea is named after a man who, in order to illustrate the damaged relationship between the Lord and Israel, was required to take a flagrantly promiscuous woman, a prostitute named Gomer, as his wife — surely one of the most unpleasant church callings in history.

When Jesus criticizes “an evil and adulterous generation” or “a wicked and adulterous generation” that “seeks for a sign” (as in Matthew 12:39 and 16:4), that description should probably be understood in the light of the Old Testament imagery of God as husband and Israel as wife. So should the Parable of the Ten Virgins (also known as The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins, Matthew 25:1-13), in which the “bridegroom” for whose coming they (and we) are to be alert is clearly Christ.

It’s noticeable, however, that Jesus calls himself “bridegroom” (νυμφίος) rather than “husband.”

Whereas, in the Old Testament, the marital relationship has already been established between God and his people, presumably via the Abrahamic or Mosaic covenant (or both), in the New Testament, it’s in the future rather than in the historic past. This is, in other words, to be a new covenant — perhaps the very “new covenant” (Hebrew בְּרִית חֲדָשָׁה [bərîṯ ḥăḏāšâ]; Greek Septuagint καινὴ διαθήκη [kainḕ diathḗkē]) that Jeremiah 31:31, already cited above, had suggested would come.

The Greek phrase that’s translated into English as “The New Testament” is, precisely, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη (“The New Covenant”), just as the Septuagint version of Jeremiah 31:31 has it.

Posted from Richmond, Virginia