(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

This is an exceptionally busy week for me, and I have another (very lengthy) book that I need to have finished by Sunday evening. But I’ve begun, in stolen moments, to read a page or two in Jeff Wynn and Louise Wynn, Everyone is a Believer: The Growing Convergence of Science and Religion (2019).

Here’s a summary of an interesting tale that they tell on page two:

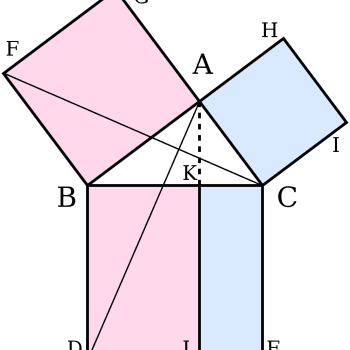

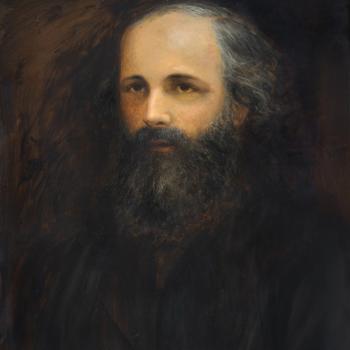

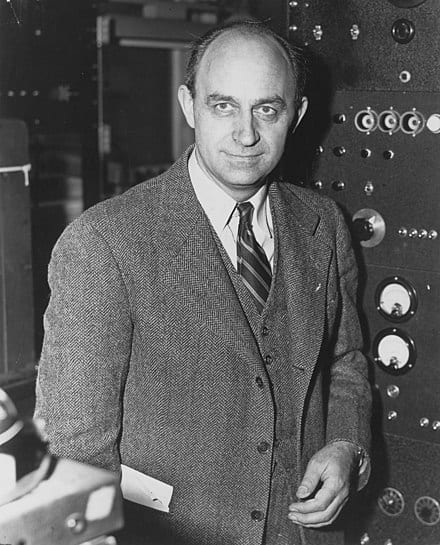

In the 1930s, the physicists Wolfgang Pauli and Enrico Fermi were trying to understand the phenomenon of beta decay. What is beta decay? I hope that I have this right: An atomic nucleus suddenly emits an electron and changes its atomic number by one, thereby becoming an altogether different element. Curiously, though, while charge was definitely conserved through this sudden radioactive decay, and while mass seemed to be conserved, spin — that is to say, angular momentum — was not conserved. Having never seen the Law of Conservation of Angular Momentum violated, Fermi believed it to be inviolable, and he could not believe that it was violated in this case, either.

Eventually, Fermi and Pauli proposed that another particle, previously undetected, was being emitted simultaneously with the electron. However, it had to be a particle without mass (rather strange, that) and without charge, because both charge and mass appeared to be conserved through beta decay. But it also had to be spinning, in order to account for the change in angular momentum that had been observed in the emitting atomic nucleus.

In a conversation with Fermi, an Italian, the Italian physicist Eduardo Amaldi suggested that they call this previously unknown and undetected — and, to this point, purely hypothetical — particle a neutrino (roughly, “a tiny little neutral thing”). And that name has stuck.

But here’s an interesting aspect of the story: Fermi and Pauli were thinking about neutrinos in the 1930s. However, it was not until 1956, roughly two decades later, that the American physicists Clyde Cowan (1919-1974) and Frederick Reines (1918-1998) were able to tentatively verify the existence of neutrinos. (Enrico Fermi was already dead by then.) In 1995, almost forty years after Fermi and Pauli proposed its existence, Reines won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his role in demonstrating that neutrinos are real. (Sadly, Cowan had died of a sudden heart attack twenty-one years earlier and, consequently, was ineligible to receive a Nobel. The Nobel Prize is never given posthumously.)

The moral of this story, to my mind — one of them, anyway — is that the progress of science isn’t simply a matter of formulating a hypothesis and immediately verifying it (or disproving it) by means of an experiment. Quite often, the interval between a proposal and its confirmation is very long. Such stories could be multiplied many times.

Another thing to note: Of the four very prominent physicists mentioned above, three died quite prematurely. Their full potential was certainly not realized in this life. Such stories suggest a good reason, in my mind, for hoping that there is a life beyond.