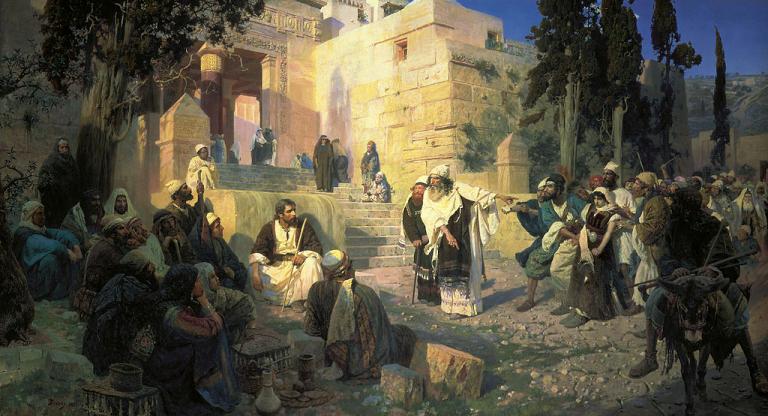

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

This is one of the most famous stories from the life of Christ.

It’s also absent from the most ancient manuscripts of the New Testament. (In some other early manuscripts, it appears after John 7:36, or after John 21:25, or even after Luke 21:38, with some textual variations.)

Does that mean that it’s not authentic?

Not necessarily. But the situation is . . . well, a bit curious.

The story remains a great one, though.

And, beyond dispute, it’s very old.

If you know Jesus, in some significant sense, you know the Father — of whom Jesus is a perfectly faithful representation.

Jesus speaks very enigmatically here, and “the Jews” predictably fail to understand him.

One of the central points to take away from the passage, though, is entirely clear: “You will die in your sins unless you believe that I am he.”

That applied to them then, and it applies to us now.

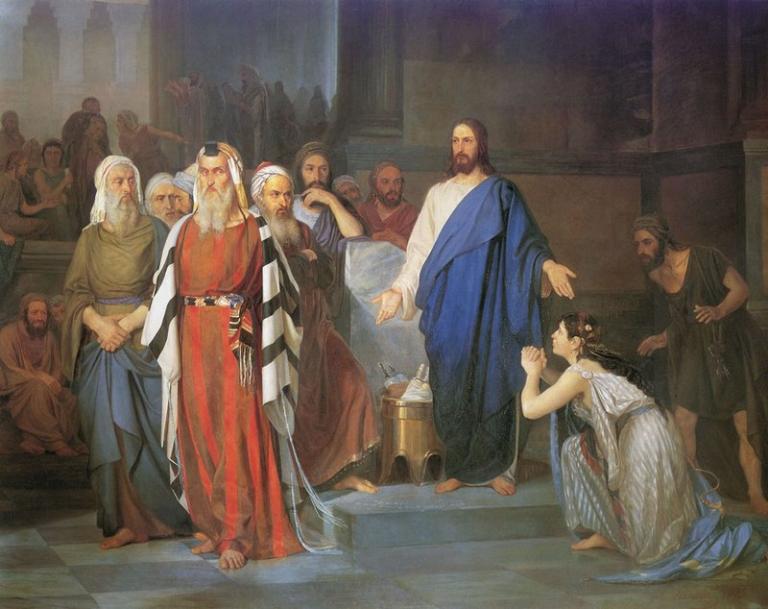

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I’ll note two ideas in this passage:

First is the concept that knowing the truth makes one free — and that, by implication, ignorance of the truth is a kind of bondage. That’s remarkable, actually.

And the more important the truth in question, the richer the freedom (or the deeper and more oppressive the bondage).

Second is the apparent confidence among the Jews to whom Jesus was speaking that there was particular merit in their lineage — merit that would save them, or that would redeem them from their personal faults and follies. They felt that they couldn’t be slaves because they came from good stock. But virtues aren’t automatically inherited, and having fabulous parents, while it can obviously be an asset, can also, if we fail to take advantage of that asset, merely emphasize the contrast between their goodness and achievements and our own failures.

Ultimately, we make ourselves. Or break ourselves.