First, some practically-useful science stuff:

“Skipping breakfast tied to higher risk of heart-related death, study finds”

***

This is entertaining:

“Why English Is One of the Weirdest Languages”

And, speaking of communication, here’s an item out of BYU:

***

The Accidental Universe: The World You Thought You Knew. Lightman, an American physicist and writer, has served on the faculties of both Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is currently a “professor of the practice of the humanities” at MIT. He doesn’t seem to be a fan of “intelligent design” or of the use of apparent cosmic fine-tuning in support of theistic belief:

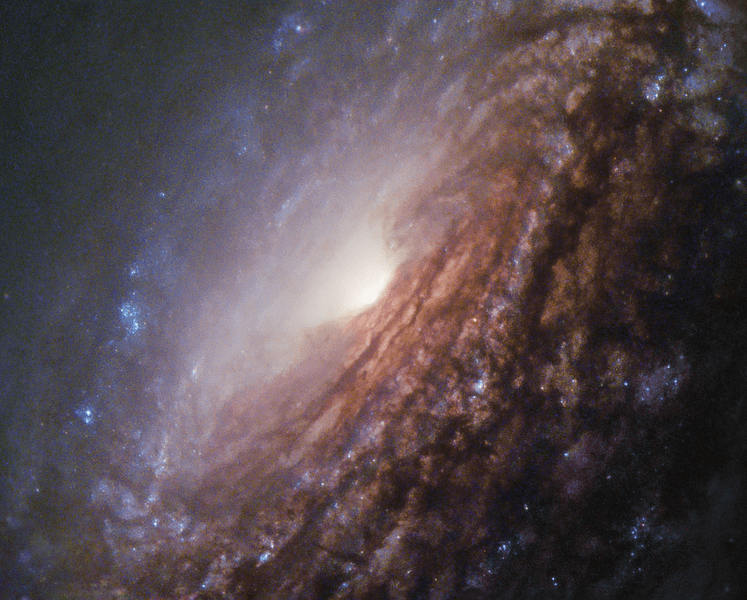

Intelligent Design is an answer to fine-tuning that does not appeal to most scientists. The multiverse offers another explanation.

If there are zillions of different universes with different properties—for example, some with nuclear forces much stronger than in our universe and some with nuclear forces much weaker—then some of those universes will allow the emergence of life and some will not.

Some of those universes will be dead, lifeless hulks of matter and energy, and some will permit the emergence of cells, plants and animals, minds.

From the huge range of possible universes predicted by the theories, the fraction of universes with life is undoubtedly small. But that doesn’t matter.

We live in one of the universes that permits life because otherwise we wouldn’t be here to ponder the question.

Our universe is what it is simply because we are here.

The situation can be likened to that of a group of intelligent fish who one day begin wondering why their world is completely filled with water.

Many of the fish, the theorists, hope to prove that the cosmos necessarily has to be filled with water. For years, they put their minds to the task but can never quite seem to prove their assertion.

Then a wizened group of fish postulates that maybe they are fooling themselves. Maybe, they suggest, there are many other worlds, some of them completely dry, some wet, and everything in between.

I can’t help but think, in this context, of the English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, and theologian William of Ockham (ca. 1287-1347) and his famous “law of parsimony,” generally known as Occam’s razor or Ockham’s razor. Boiled down to its essence, it holds that simpler solutions are more likely to be correct than complex ones, that one should, on balance, select the answer or explanation or hypothesis that requires the fewest assumptions.

Curiously, Ockham’s razor can’t be found in its familiar form in any of William’s writings. But there are expressions of a similar sentiment. For instance, in his theological treatise on the Sentences of Peter Lombard he writes Numquam ponenda est pluralitas sine necessitate (“Plurality must never be posited without necessity”).

“Zillions” of universes seem pretty plural — to me, at least.

One famous later formulation of Ockham’s razor that doesn’t precisely occur in any of his preserved texts seems especially apropos here:

Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem

“Entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity.”

And, again, to posit the existence of “zillions” of universes in order to escape potential theistic implications of cosmic fine-tuning seems to me a pretty impressive example of multiplying entities.