I published the article below on 21 February 2018, in Salt Lake City’s Deseret News:

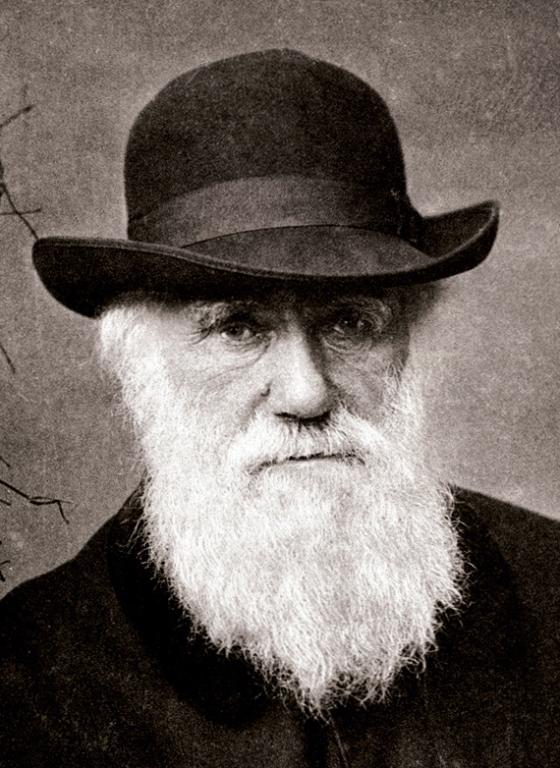

In December 1831, when HMS Beagle undertook her five-year second voyage, a 21-year-old gentleman named Charles Darwin was aboard. Serving as the ship’s “science officer,” he planned to become a country parson upon his return. By his death in 1882, however, Darwin considered himself an agnostic; although rejecting the term “atheist,” he went for walks when his family attended worship services.

What had happened during the intervening five decades? He had, of course, published the epochal books “On the Origin of Species” (1859) and “The Descent of Man” (1871), and had introduced the revolutionary “Darwinian” theory of evolution — although, in justice, Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) probably deserves credit as “Darwinism’s” co-discoverer.

Evolution has been seen by many, and welcomed by some, as a threat to religious faith. And, truly, his research on the Beagle and thereafter challenged Darwin’s religious views. For instance, divine design seemed to provide no plausible explanation for the variations that he observed between tortoises in the Galapagos Islands.

But it was nature’s sheer cruelty that evidently troubled him most. Cute kittens play with balls of yarn, for example. But cats also play with — effectively, they torture — mice that they’ve caught. And Darwin was horrified by the way Ichneumonidae wasps reproduce — depositing their eggs inside a paralyzed caterpillar, where the hatchlings gradually consume the still-living caterpillar’s internal organs before they emerge.

This was the age-old problem of evil, of reconciling belief in a benevolent God with the existence of injustice and suffering. It was a challenge that Darwin’s faith couldn’t withstand.

Still, his biological research didn’t destroy Darwin’s belief in God. The lethal blows came much closer to home.

Darwin was a devoted father and family man. Unfortunately, in late 1842, his daughter Mary lived less than a month. And baby Charles died in 1858, halfway through his second year.

His father, Robert Darwin, died in 1848, and pious suggestions that Robert was now undergoing torture in hell deeply offended Charles Darwin. The idea that “my Father, Brother and almost all of my friends will be everlastingly punished” seemed to him “a damnable doctrine.”

Then in 1851, just three years after his father’s passing, his beloved 11-year-old daughter Annie contracted a serious disease, possibly tuberculosis. And, despite Emma Darwin’s passionate and devout prayers, Annie died, too. Darwin was heartbroken, his faith shattered. He never stopped mourning his children.

In the end, he wanted only to be buried next to them in St. Mary’s churchyard, southeast of central London. For him, sadly, it was “the happiest (place) on earth.” However, perhaps intending a public statement, his followers insisted that he be interred in Westminster Abbey, near Sir Isaac Newton.

Reading the story of Charles Darwin — not merely the illustrious scientist, but the agonized observer of ghastly suffering and the grieving father — one wishes that faith in the restored gospel might have given him the peace that eluded him. And we can hope that, by now, he has found that peace — and Mary, Charles and Annie.

“All your losses will be made up to you in the resurrection,” declared the Prophet Joseph Smith, “provided you continue faithful. By the vision of the Almighty I have seen it.”

The doctrines of the Restoration foretell a time when “all now mysterious shall be bright at last.” In the meanwhile, as Jane Borthwick’s English hymn lyrics counsel, _Be still, my soul: Thy best, thy heav’nly Friend__Thru thorny ways leads to a joyful end. …__Be still, my soul: The hour is hast’ning on__When we shall be forever with the Lord,__When disappointment, grief, and fear are gone,__Sorrow forgot, love’s purest joys restored.__Be still, my soul: When change and tears are past,__All safe and blessed we shall meet at last._ (“Hymns,” No. 124)

In the wake of the massacre of innocents at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida — just one of the horrors with which news and history are saturated — faithful members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints admit, with the apostle Paul, that in this life “we see through a glass, darkly,” and, with Nephi, that we “do not know the meaning of all things.” Nevertheless, also with Nephi and Paul, we “know that (God) loveth his children” and that love is the greatest of all gifts. (see 1 Nephi 11:17; 1 Corinthians 13:12-13).

And we testify that, even “should we die before our journey’s through,” “All is well!” Even amid sorrows and horrors, the gospel remains the very best of good news.

Posted from Herzliya, Israel