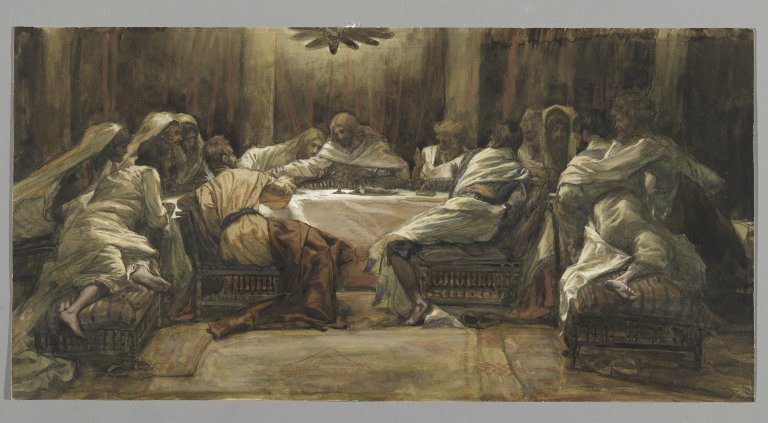

by James Tissot (d. 1902); Wikimedia Commons public domain image

Compare Luke 22:21-23

Two quick observations:

1.

Each of the eleven apostles who were innocent in this matter worried that he might be the one who would betray Jesus. This is commendable. On this occasion, at least, none of them seems to have imagined himself invincible, impervious to sin or temptation.

We should all recognize our own capacity to mess up badly. Those who don’t recognize it, I think, may often be in considerable danger.

Judas, of course, asked the question “Is it I?” quite insincerely. He was posing. He knew full well that he had already entered into an agreement with the leaders of the Jews to betray Jesus.

2.

It’s important to recognize the principle expressed here that, while evils occur in this fallen and mortal world — and even do so, generally speaking, as part of the divine design (just as Christ’s death and atonement were specifically designed and intended by God) — that doesn’t get those who perpetrate them off the hook.

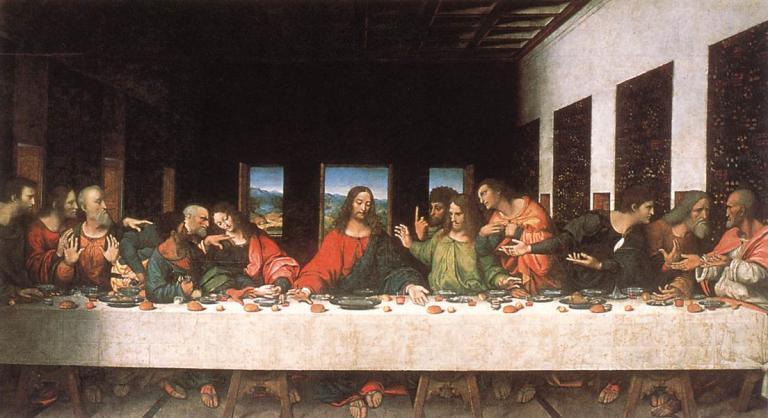

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

Compare John 6:51-58; 1 Corinthians 11:23-25

It’s striking to me that, while the ordinance of the sacrament (as Latter-day Saints understand it) was instituted in the Old World and commemorates events that occurred there, the actual sacramental prayers that we use today come from the Nephites. (See Moroni 4 and Moroni 5.)

Compare John 13:21-30

Somebody evidently needed to play Judas’s part in the drama of atonement and salvation. For that matter, I suppose that somebody needed to play Satan’s part, as well.

However, neither of them will be rewarded for fulfilling these roles.

Likewise, in order for this mortal probation to be complete there must be betrayals and unkindness. But those of us who commit treacherous and unkind acts should expect no thanks for them.

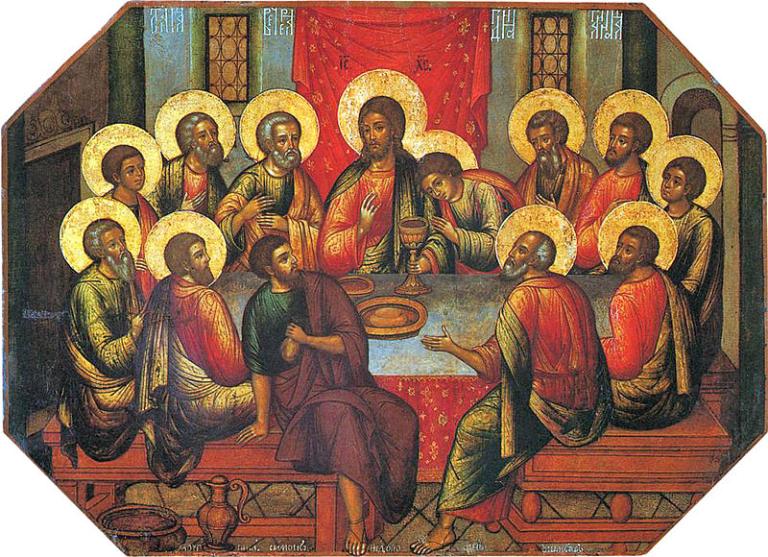

Compare Matthew 19:28; 20:24-28; 23:11; Mark 9:35; 10:41-45; Luke 9:48; John 13:4-5, 12-17

These apostles were good men. Their selection and their subsequent biographies demonstrate that. But they still had problems with their desire for approval and status.

Surely the battle against our own egos is among the hardest we face. Even when we do good things, and even when we do self-denying things, it’s difficult not to want our goodness, our humility, our self-abnegation, to be noticed. It’s hard not to be proud of one’s humility.

Combatting our desire for wealth, even for simple status and recognition, is difficult enough. But the fight isn’t over even then.

Life is hard, as the saying goes. But what’s the alternative?

Posted from Abingdon-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, England