(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

First, in order to set the stage, I offer my hasty translation of Qur’an 7:172-173:

And when your Lord took their descendants from the children of Adam, from their loins, and caused them to testify against themselves. “Am I not your Lord?” “Yes, we have testified.” Lest you should say, on the Day of Resurrection, “We were unaware of that.”

Or should say “Our fathers were idolators before us, and we are their descendants following after them. Will you destroy us for what the falsifiers have done?”

The commentators have discussed and argued over these verses for many centuries, since the beginning. Some have suggested that they refer to a sort of covenant in a sort of human pre-mortal existence. One might argue, if that is true, that it’s because we humans entered into a covenant, or contract, or agreement with God before we came to this world that God can properly hold us accountable for our actions in this life.

Pre-mortal existence isn’t a doctrine of the Qur’an otherwise, though one might argue that the Qur’an’s constant description of death as a “return” to God implies something of that sort. (One can’t really “return” to a place or a person when one has never been there in the first place.)

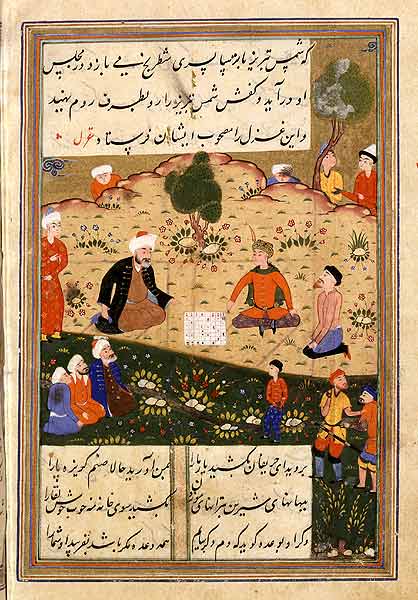

And the antemortal existence of human beings isn’t a doctrine of mainstream Islam, although some thinkers (such as the great philosopher Ibn Sina or Avicenna [d. AD 1037] and the equally great Persian mystic poet Jalal al-Din Rumi [d. AD 1273) seem to have believed that humans lived before they came to earth.

For instance, Rumi begins his magnificent Persian-language poem the Masnavi (or “Couplets”) with an extended reference to the plaintive sound of a reed flute, which reminds him of the yearning of the human soul for a return to its divine home:

Listen to this reed as it is grieving;

It tells the story of our separations.

“Since I was severed from the bed of reeds,

in my cry men and women have lamented.” (1-2)

This is the familiar ache of homesickness.

Whoever finds himself left far from home

looks forward to the day of his reunion. (4)

Far from ordinary, though, it’s cosmic homesickness.

Reflect upon this story, my dear friends;

its meaning is the essence of our state. (35)