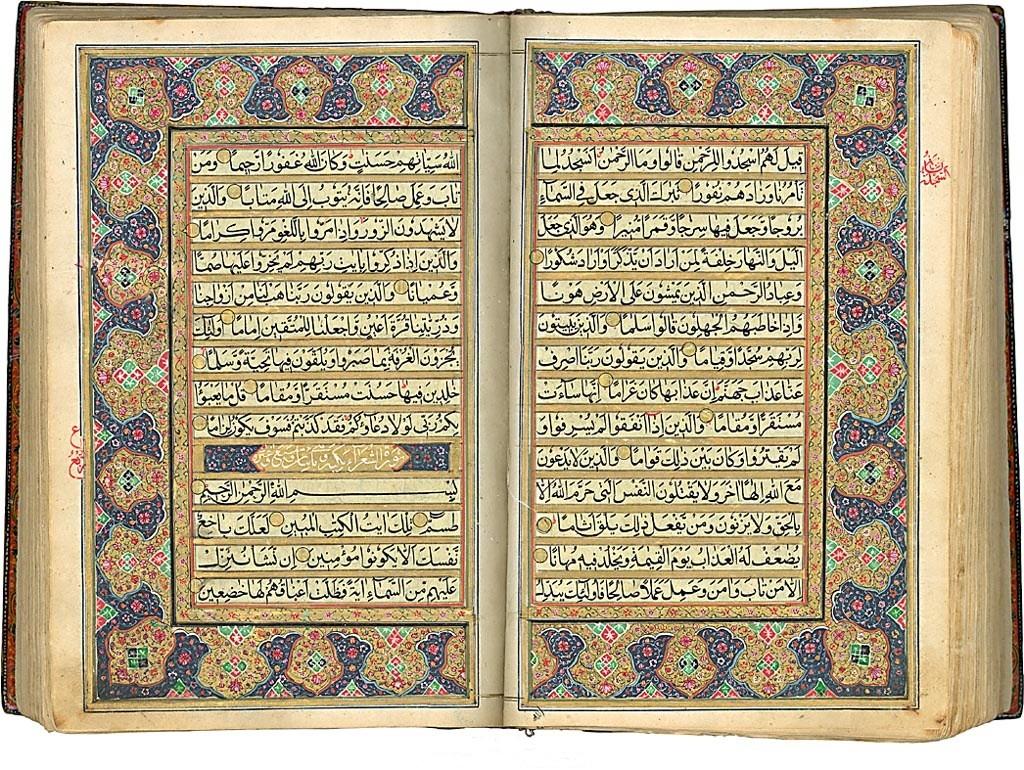

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

It is essential to recognize, first, that the term jihad doesn’t actually mean “holy war,” although it is certainly used primarily in that sense and although it certainly can be and often is used to refer to literal, physical, military combat.

The word jihad comes from the triconsonantal Arabic root jhd, which has the basic meaning of “striving,” “working,” or “exerting.” Other derivatives from the same root include the verbs jahada, ajhada, and ijtahada, which mean, respectively, “to endeavor” or “to strive”; “to strain,” “to exert,” or “to fatigue s.o.”; and “to put o.s. out” or, in an Islamic legal context, “to formulate an independent judgment regarding a matter of law or theology.”

Both jahd and juhd denote “strain” and “exertion.” Ijhad refers to “exertion” or “overexertion.” Ijtihad denotes an act of independent theological or legal judgment by a qualified jurist, based upon acknowledged principles and rules, and a mujtahid is such a qualified jurist.

I will now begin to address specific passages in the Qur’an — all translations are mine, unless otherwise indicated — that are often mentioned when the subject of the Qur‘an and violence is raised:

Qur’an 2:216: “Fighting (al-qital)has been prescribed for you, although it is hateful to you. Perhaps you hate something that is good for you. Perhaps you love something that is bad for you. God knows, while you do not know.”

Qur’an 2:244: “Fight (qatilu) in the path of God, and know that God is hearing and knowing.”

There can be little question that both of these passages concern literal fighting in war; the root qtl that is used in them (instead of jhd) connotes the idea of “killing.”

But historical context is all-important here. Every scholar and commentator agrees that, while Sura 2 (al-Baqqara or “The Cow”) was probably revealed over an extended period of time, it is entirely a Medinan chapter. That means that it was given to the Prophet Muhammad after his flight or emigration, his hijra, from Mecca to Medina. That flight was enforced upon him by the persecution that he and his followers suffered in Mecca, which eventually resulted in their exile, the loss of their property, and so forth. In that sense, a state of war already existed between the exiles in Medina and their tormentors in Mecca, and battles had already occurred.

Imagine an order from Dwight D. Eisenhower mandating the bombing of Berlin, Munich, and Frankfurt. In considering that order, it would make an enormous difference if it had come from General Dwight Eisenhower in his capacity as supreme Allied commander in 1944, during World War Two, or from President Dwight Eisenhower in peacetime 1954. In the latter case, we would consider him a homicidal lunatic. In the former, we would merely sigh and admit that that’s how things are done in wartime.

To be continued.